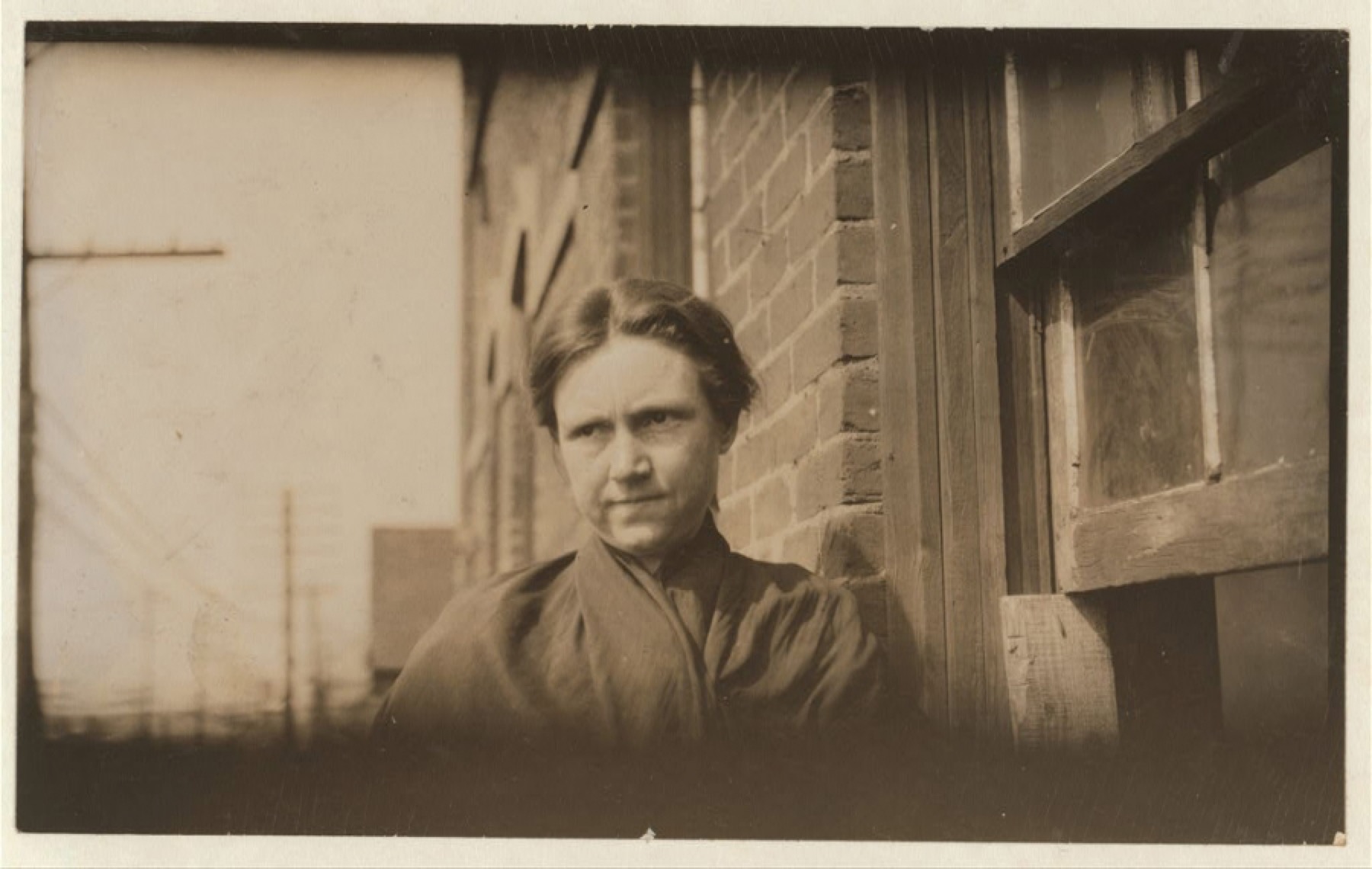

National Child Labor Committee collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

A FAMILIAR STRANGER

By Julien Baker

Getting Out of the Way

I

wake up to labored grunts and aggressive rustling, the unmistakeable sound of someone losing a battle between their overfull luggage and an overhead compartment.

“Sorry, he’s spatially inept,” says the woman next to me, apologizing for her husband as he scoots clumsily across the airplane row.

We are about to depart for a seven-hour flight from Lisbon to Boston—for me it is the second of a four-flight journey home that sacrifices convenience for cost-effectiveness. Having woken up at three a.m. to begin the jaunt, I had already dozed off before boarding was complete.

The older couple shuffles into the seats next to mine, the woman expelling a stream of apologies and oh-dears as she fiddles with her luggage and seatbelt. She seems genuinely distraught for disturbing me. Through a fog of exhaustion I try to convince her of my un-botheredness by making polite conversation, and ask if they were on vacation in Lisbon. She tells me they’ve actually been on a tour of Europe through Prague, Vienna, and Berlin.

“Quite a trip!” I observe, my enthusiasm sounding accidentally stiff.

“Oh, yes! We just love traveling, seeing new places, learning about history!” she says, beaming like an unjaded tourist, patting her husband’s shoulder as he looks out from a wide-brimmed trucker hat and grins adoringly in agreement. She asks what brought me here. I tell her I’m a musician and have been touring in Europe.

“A musician!” the woman gasps. “Robert, Robert!” She flaps a hand at her husband, who is already watching an in-flight movie. “This girl is a real musician!”

She asks where home is and I tell her I live in Nashville.

“Music City!” Robert comments, jovially, removing an earbud.

“We’ve always wanted to go there!” the woman says. “I’m from Canada originally. Robert is from Detroit. When we fell in love, I moved over here, became a citizen.” She gives him a wink and Robert shrugs bashfully.

She tells me the two have since retired, and now live in Tampa, Florida, using their free time to see the world. We talk about the educational benefits of traveling, the perspective gained from being exposed to the unfamiliar, the importance of humbling oneself as an outsider in a foreign environment. I remark that for all the cultural variance of all the places I’ve been, I’ve been surprised at how other countries are facing socio-political problems not unlike those in the the United States.

“God, I know, it’s happening everywhere. And the politics in the U.S. are a mess. I’m so angry with the Democrats.” She shakes her head in ambiguous disappointment, then, pivoting her whole body toward me, she asks point blank, “so did you vote for Trump?”

Wow lady, you don’t waste any time, I think.

I hesitate and, sensing my discomfort, she says, “In Canada we don’t think it’s so weird to talk about who you vote for. I think Trump’s a buffoon anyway—I voted for Bernie. He wanted to actually change things, and I was with him. I was in the street, all ‘Hey hey, ho ho, corporate greed has got to go!’” She shouts the rally slogan emphatically despite the dimmed cabin lighting. A passenger across the aisle lifts his face mask in annoyance. I tell her I was a supporter too, but felt torn about using my vote for a write-in.

“Ugh,” she scoffs. “Well, I guess I just can’t believe Hillary got the nomination. That’s why I’m upset with the party.” She criticizes Super PACs and lobbyism, bewailing the use of wealth to purchase political influence.

“You wanna know why I loved Bernie? Health care. How do we still not have national health care? Everyone says it’ll bankrupt the country, but medical costs are the leading cause of bankruptcy in the states!” She leans forward, fuming. “Robert used to work in hospital administration and you know what their meetings were about? Increasing profit. Not helping people. It’s 2018, people should have a right to health care, a right to education too.”

She tells me of her time spent teaching history and social sciences, how undervalued education is. I tell her of my cursory experience with the education field. We commiserate about the woes of underfunding and gerrymandered zoning in the public school system.

“It’s all business. Health care is a business, politics is a business, they’re all in cahoots with each other.” She trails off despondently, drawing her lips sternly as she simmers. I offer a dejected “yeah,” and we exchange the sighs of exhaustion that punctuate indignation at overwhelming wrong.

Abruptly, she jerks toward me and and asks in a voice suddenly grave and bewildered, “do you think the FBI is good?”

I’m unsure how to answer. Is she asking if it’s good to have a Federal Bureau of Investigation, if I think there are redeemable parts of a corrupt institution, if I think there are at least some moral people who work for the FBI? I produce a confused and inarticulate “uhh.”

She clarifies. “I mean, have you seen what’s happening now, with this trial?”

She’s referring to the Senate Committee hearing regarding Trump’s Supreme Court appointee Brett Kavanaugh and the testimony Dr. Christine Blasey Ford gave regarding her sexual assault by Kavanaugh.

“It was disgusting, evil,” she says, “They already had their minds made up! Why do you think they had her testify, if they didn’t believe her?”

Her question is not rhetorical, but in the long, heavy pause I can’t muster any explanation.

“The way they talked to her, called it an unethical sham—do you realize what that says to women? It says, ‘You’re powerless. You’re invisible.’ Men don’t realize how much power they have. There are good ones; my Robert is good. But they don’t understand just what it is like to be invisible. They can’t.

“Even my son,” she says, her tone ebbing from outrage to sadness, “he’s a good kid, but I think he still needs perspective.”

I nod quietly. In the empty gap of silence she meanders from sexism and political inequality and tells me about her son, his teaching positions in various parts of Asia and Africa, and his transition to his current occupation: getting elderly people signed up for government aid and health-care programs that they don’t know they are eligible for.

“The government won’t advertise it, obviously, so they don’t know. He goes around on visits trying to help, but he’ll hang around two, three hours. Makes friends with them, calls them later to see if they need anything.”

“That’s sweet,” I say. She tosses me a skeptical smirk.

“He’s sweet but he’s too—” She furrows her brows in exhausted confusion. She’s reluctant to use the word soft. “He gets taken advantage of. He’s always giving people second, third chances, getting ripped off. It’s good to be nice—I just want him to be—” She gropes for words in the air, “—tough. I want him to fly.” I ask what it would mean for him to fly.

“Make more money for himself,” she says flatly.

Earlier this woman had decried corporate greed, criticized capitalism, and condemned a culture that values profit over compassion. But in the microcosmic setting of her daily life, failing to prioritize individual success and wealth was not radical, nor laudable, but foolish.

“I want to tell him straight, but I know I’d hurt him. He just can’t go around doing everything for everybody. He’s such an intense person, so sensitive.”

As she muses aloud about whether it’s better to raise a child to be compassionate but naive, or shrewd but callous, I think of my own tendency toward the willful naivety of a bleeding heart, the way it has been ironically challenging to the people I love most. I think of my partner’s concern when I would pick up hitchhikers, loan money I might never get back, miss important personal obligations because I felt I was morally moved to attend a march or demonstration protesting one of this administration’s innumerable injustices. I think of my mother negotiating the line between insulation and exposure, of the times when my fragile adolescent ego was wounded by the brass tacks she considered a vital part of education.

“I’ve always been that person who tells it like it is, doesn’t take any bullshit,” the woman continues, “but being a single mom, even being a woman alone, I think I had to toughen up. I didn’t have an option.”

I think about the women I know from the generations before mine, their unwillingness to take any shit, their employment of the phrase “fend for ourselves.” Suddenly I am listening to a random stranger from Canada echo the crass Southern axioms shared between my mother and her sister.

I think of my mother’s belief in self-reliance, her commitment to the unglamorous, mandatory toil of survival. I remember her recounting the oral history of our rural ancestors, accompanied by yellowing photos of my extended family standing next to plows and upside-down hogs. Her stories were fable-like yarns of distant country relatives who lived crude but humble lives, who embodied the paradigm of American rugged individualism.

Her mother was characterized by her resilience but also her harshness; she had lived in a holler nestled in the East Tennessee mountains, worked on an assembly line in a shirt factory, and been a divorced woman at a time when divorcées were ostracized. When my relatives reminisce about her, they remark often about her stubbornness, her confrontational tenacity. Neither sentimental nor delicate, her affection manifested in stoic devotion rather than fawning tenderness. They retell anecdotes of her making a scene by shouting at the high school band director for refusing to let my mother march with the other children and by striding onto a Little League field to publicly lambast the coach for not including her sons in the game. For lack of a better expression, she raised hell.

Some of my mother’s stranger memories were of family meals from Dairy Queen being eaten in the car because her mother refused to go inside.These stories seemed inconsistent with the other points of my grandmother’s character, but also much like the behavior of a person who sees herself, at least subconsciously, as an outsider—a person whose lack of resources or knowledge had placed her in a separate social category, one that demanded toughness but that also created otherness. My mother describes a similar otherness, a keen awareness of not-having. Her adolescence was defined by her waitressing at a drugstore, saving money, and funding her own schooling by applying for grants and scholarships. My mother had adopted the performance of strength that was modeled by my grandmother—one expressed in emotional fortitude and solitary determination. And she had excelled: my mother put herself through school, studied abroad, and shook Jimmy Carter’s hand after winning a statewide essay competition.

These achievements were a blueprint of character, a family mythology told in parables which prizes work ethic as the most essential quality of a citizen. It is an iteration of a common blue-collar catechism taught in countless households that maintains each person must struggle nobly for themselves. This tenet is presumably meant to engender confidence and motivate us to achieve, but it also socializes us to believe a perplexing contradiction.

From childhood we are instilled with the ethics of generosity and equality—taught to take turns, to share, and to advocate for the weak. Simultaneously, we are indoctrinated with the covert certainty that unsuccessfulness is the result of laziness. It is important to be kind, but more important to be productive. Our culture criminalizes poverty and stigmatizes welfare, critiques the greed of the super-wealthy while disapproving of programs that redistribute that wealth to provide for its citizens because of the entitlement an entire class feels to their own wealth. I remember hearing relatives argue against public health care with a decontextualized reference to Thessalonians: “if you don’t work you don’t eat,” and wondering how this draconian detachment from the plight of the unemployed could coexist with a professed belief in the value of compassion. We are taught to value mercy and grace alongside fairness, forgetting that often what is gracious, merciful, or compassionate is often not what is technically fair, at least by the Hammurabian standard of an eye for an eye.

This dichotomy of belief forms a functional cynicism, something that we tell ourselves we need to survive but which allows our adversity to become something that breeds resentment for others’ hardship instead of sympathy for it, and makes us reluctant to challenge a dominant system.

I admit to the woman that I’m guilty of the same softness she describes in her son, tell her it was a long time before I learned how to to suspend the moral crisis of living so that I could actually live, how to stay balanced.

“Balance,” she whispers deliberately. “Exactly.”

I say I think radicals and centrists need each other, and she chuckles. I tell her the relationships that have taught me the most about myself have been with those who are most unlike me, that I think balance isn’t the dulling of passion or absence of extremes, but the ability to assimilate other perspectives into your understanding of your own convictions.

I tell her it took years of heated conflict between my mother and me before we learned to hear each other, before we could contextualize our disagreements in each other’s lived experience.Women like my mother, her sister, my grandmother, like this stranger on the plane, have little patience for the privileged idealism that fails to acknowledge the cold, hard facts of life, what the matrons of my family would call the Ivory Tower during inevitable clashes of politics at Thanksgiving dinner. As a teenager attempting to reconcile the ingrained biases of my family environment with my own inchoate ideologies, I remember ridiculing the Spartan principles they espoused as unsympathetic. As an adult, my convictions are the same, but the coarseness I recoiled from judgmentally I now interpret as pain lost in translation, converted into cautionary sternness.

It was not until I did the hard work of listening that I understood those Spartan principles were part of an inherited manual for living handed down in the unique mythos of our family. Their hardened self-reliance was not an arbitrary or even conscious belief; it is an abstraction of personal history, renamed. The more that I began to value stories, the more I could hear the implicit references to that history that provide reference points to practice empathy for another person’s experience. Understanding biases does not make them benign, but identifying their motivations gives us the tools to deconstruct them; listening to each other’s stories lets us cobble together an emotional pidgin language—a shared vocabulary of experience that helps to unravel motivations and biases, peel back the superficial layer of our ideologies and reach something common and human.

“Getting Out of the Way” is a part of our weekly story series, The By and By.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.