A ROCK STAR, ONLY BETTER

By Holly Gleason

In Memoriam: Chet Flippo (October 21, 1943–June 19, 2013)

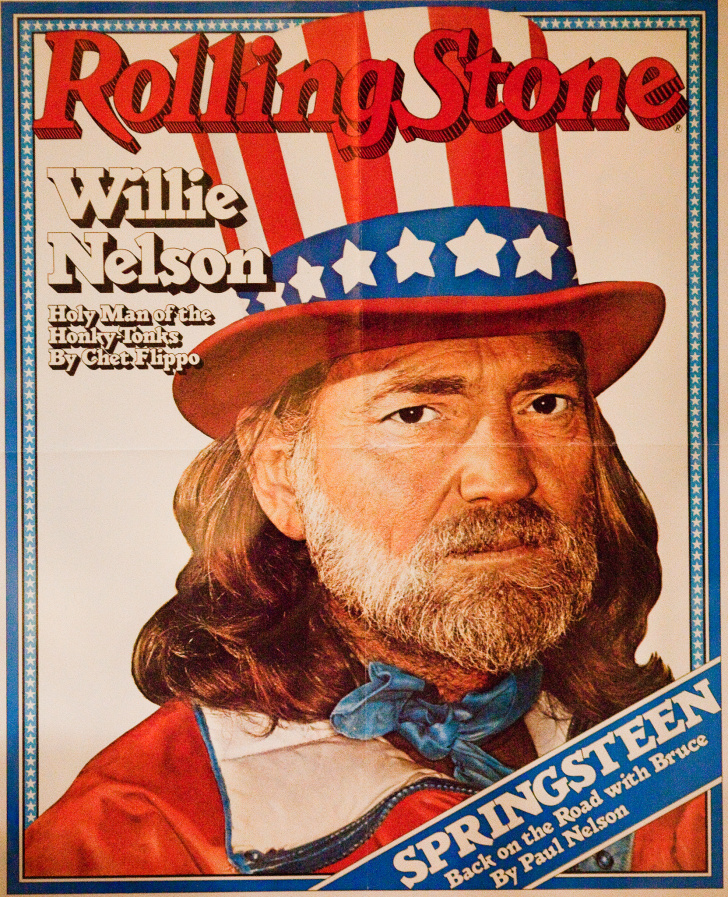

One Chet Flippo's many Rolling Stone cover stories, 1978

One Chet Flippo's many Rolling Stone cover stories, 1978

When I got the news I pulled off I-65 North and nosed into the Spalding University Library. En route from Nashville to Cleveland, it felt like someone had punched me in the stomach. Chet Flippo—the storied Rolling Stone editor who’d gone toe-to-toe with Mick Jagger, smoked cigars with Uma Thurman, helped land Willie Nelson dressed as Uncle Sam on the cover of the magazine, igniting my pre-teen imagination—had died.

I was introduced to Chet’s ability to weave details and conversation into narrative at the age of twelve. My Midwestern parents didn’t believe in rock & roll, so access to the forbidden was a thrill. Rolling Stone became my addiction and Chet Flippo my drug of choice. I was lost to the tales of Mick and Keith on “the Road,” Dolly Parton’s New York City apartment, and a firecracker Lolita of a country singer named Tanya Tucker.

Chet Flippo didn’t just get it, he felt it. He let me feel it, too. And when eleven people died at the Who concert in Cincinnati, he captured the moment and shattered my innocence about the real world with his clear-eyed reporting, tempered with empathy and compassion.

Chet Flippo was a rock star, only better. He moved among them, but he remained one of us—and he shared not just their heroics, but their boils and bald spots. For Chet, the truth was a measured substance with which to measure hubris and genius. And he let us see that world through his very clear eyes. To a young girl with no experience, he made rock & roll visceral and real.

So when Liz Thiels, the very dignified uber-publicist, asked if I’d like to interview Chet in the corrugated metal-roofed “media center” at the Nashville fairgrounds in 1984, I almost fell over. A nineteen-year-old college girl making her first trip to Music City for Fan Fair, the yearly gathering of country stars saying “thank you” to their fans, I was tired, dirty, and absolutely willing. Why wouldn’t Chet Flippo be ready for his close-up after a week of watching stars pose for pictures in animal barns, concerts on a small-time stock car track, and fans waving fans made of Boxcar Willie’s face?

Chet, who began writing for Rolling Stone out of Austin during the heyday of the Armadillo World Headquarters, had always had friends, like Thiels, in Nashville. He also had a book coming out right after Fan Fair—On the Road with the Rolling Stones: 20 Years of Lipstick, Handcuffs and Chemicals—and he trusted Thiels to vet the journalists who’d get it.

On a cool Sunday morning, I arrived at the appointed time, was shown into a warm, sunny apartment and was floored to see . . . Chet Flippo. In the flesh. Long thin legs, beautiful hands with long fingers (all the better to type with), and ashy, wheat-colored hair that fell across his forehead. He wore round glasses and had a warm smile that extended to the edges of a very broad face. Dignified and gracious, Chet stood and shook my hand, thanked me for coming. I almost fell over, but instead I started riffling through my South American basket of a purse for my tape recorder, so my awe could be concealed.

The conversation was vast; Chet was generous. Not just with stories about the Rolling Stones and his book, but about the realities of writing, of maintaining an editorial detachment and the power of loving the music. He even let me prattle on about his wife Martha Hume’s You’re So Cold I’m Turning Blue, a book about country music I’d found at a Hialeah swap meet and fell in love with to the point that in many ways, it informed the voice I was developing as a writer.

It was obvious that what I loved about his stories is what I loved about the man. How he saw the world as a rich and glorious thing. He never seemed bored, never acted put out. Nearly one hundred minutes into our conversation, I was spent, and sure that I’d worn out my welcome. Shyly, I asked him to sign my copy of his book, because well, I wanted proof!

After telling me I’d asked good questions and saying I could look forward to a fine career, he hugged me. I floated back to the car, which was immediately headed back to South Florida, where I was living. All the way home, I listened to the Rolling Stones, a tape of Gram Parsons that the critic from the Miami News had given me, and Will The Circle Be Unbroken, the groundbreaking hippies-meets-country old-timers recording by my friends the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, which Flippo had written the liner notes for. It was like the soundtrack of Chet.

Over the years, Chet would cross my path. Backstage at a Farm Aid, on a book tour for Everybody Was Kung Fu Dancing. He was always quietly serious, wickedly funny, and willing to share what he knew. He was also curious about others: What are you doing? Listening to? He was especially interested in what people had on their minds, to understand them better. Because that was another beautiful thing about Chet Flippo: he liked to meet people where they were, to embrace who and what they’re made of.

And so my young crush on “Chet Flippo,” the name in the magazine, turned into a powerful regard for this bespectacled man who maintained his sense of humor about my gawkiness around him, whether it was just us having lunch or an awards show press room or a black-tie dinner. Part of my awe, truth be told, was fueled by Martha Hume, and his love for this woman whose mind was a gyroscope of notions. Together they were amazing. The alchemy of their chemistry was contagious.

Chet spent a series of years as a journalism professor at the University of Tennessee. I loved the idea of young Chet Flippo–trained journalists entering the work force, writers who would want to understand not just their bias, but every plausible context for what they were capturing. Chet believed in the whole, which meant understanding the aspects of a story and the aspects’ aspects. He wanted to get it right. Once he figured that out, he used the ultimate sextant: his heart. Because Chet viewed the entire world through his heart. His heart was stout and gentle, took umbrage to the overblown and self-important. He skewered hypocrisy and punctured pomposity with a few very brief, very even observations.

He didn’t set out to be the conscience for an industry not known for its high levels of taste or artistry, but somehow in his quiet way, he knew how to get people to think about it. Just like he made a teenage girl think about the white-hot center of Tanya Tucker’s voice, the life that Paul McCartney actually led, and the glory of too much rococo that was Graceland.

Like young William Miller with Lester Bangs in Cameron Crowe’s Almost Famous, Chet Flippo always gave it to me real—and sweet. Unlike William Miller and Lester Bangs, I’m not fourteen and he is cool. Or was. Which is why I’m in a ’60s-style library on a small Catholic college campus, trying to make sense of the news.

While I was writing, my phone rang. It was Rosanne Cash, asking what had happened. As jarred as I, she confessed, “I knew you’d know . . . this has really thrown me.” I understood. I told her about the collapsed lung, the punctured diaphragm. Silence engulfed us. I threw my own medical examiner’s verdict into the ring: “I think he died of a broken heart. Couldn’t live without Martha.” “I hope you’re right,” Cash allowed. “I was thinking the same thing.”

When Martha died in December, my heart sank. Some loves are meant to be a deux. How would Chet do without the blanket of her love? Honestly, he went to work, wrote his column for CMT, was seen around. He was preparing to do a piece for OA’s music issue. But somehow he was a bit hollower than even his normally thin frame would allow.

Makes me wince to think of it. Hugging Chet just weeks ago at the memorial for Martha, where so many slides were shown, memories offered. Pictures of them in t-shirts, in grown-up clothes; one amazing portrait of the two of them, after traipsing to Mexico to be married, so Hemingway and Gellhorn that it hurt. But it didn’t hurt Chet. It made him shine. Hearing all the love, watching the pictures cascade by, he smiled and nodded, remembered a life well lived. That was his girl, and he beamed.

Ironic that the man who let me glimpse under the big top tent as a kid, to see the lions and tigers doing their tricks, then snapping at their trainers, is the one to also show me the way grace penetrates when you’re not even paying attention. I think about him standing up for Natalie Maines during the Dixie Chicks’ fall-out or writing about a twenty-three-year-old Rosanne Cash when she was just finding her way.

Losing Chet makes my heart hurt. It only hurts because of how much I loved him. More importantly, right now, he and Martha are arm’n’arm in heaven, strolling around, catching up, so glad to be together again. Sometimes what’s right in this world doesn’t feel right, but in the big picture, there’s no sweeter thing than that.

To discover more exclusives from our website, sign up for our weekly newsletter.