You Must Tell This Story

Alice Faye Duncan’s children’s books preserve Black history and the people who populate it

By Zeniya Cooley

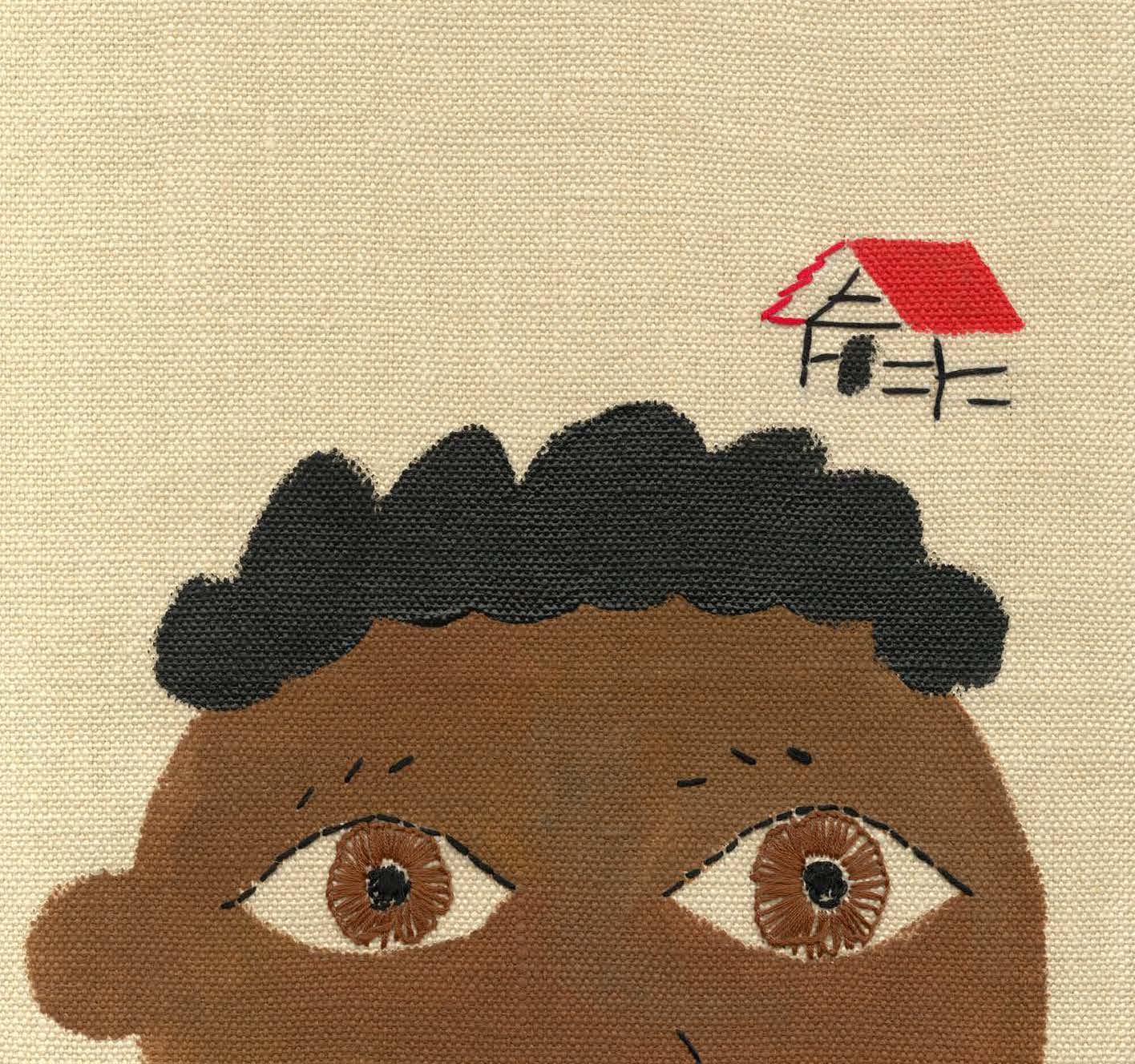

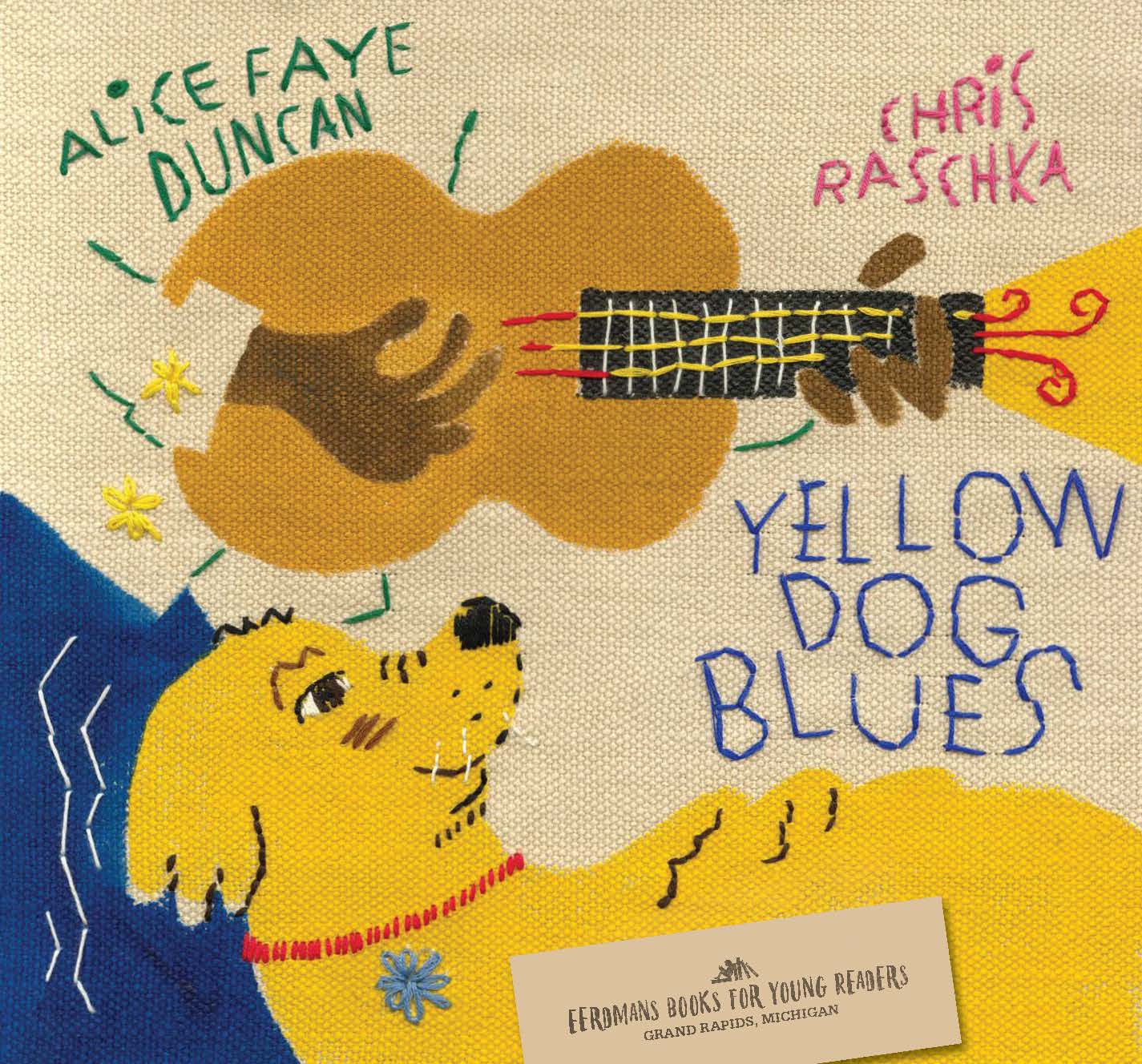

Illustration from Yellow Dog Blues. Copyright © 2022 by Chris Raschka

She has told the story of nine-year-old Lorraine Jackson marching through the fetid streets of Memphis during the 1968 sanitation strike. She has told the story of displaced sharecroppers in the mid-twentieth century, picketing voter suppression while still living in pitched tents.

Though usually accompanied by rainbow acrylics and folksy patchwork, Alice Faye Duncan’s stories are not afraid to confront grim truths. In Evicted! The Struggle for the Right to Vote, a Black man’s feet dangle in front of a gaping crowd. Thomas Brooks’s ghost addresses the reader: “My story ain’t polished. Read it anyway. Study my broken body like a book.”

Urgency and calls to action characterize Duncan’s work. “Call out the names of men, women, and children from this Fayette County movement,” she writes in the prologue to Evicted!. “Record their conquering civil rights struggle for generations to come. Remember it. Pass it on.” The heroine of Duncan’s Memphis, Martin, and the Mountaintop makes a similar appeal: “You must tell the story—so that no one will forget it.”

Born in Memphis, Duncan’s own journey began in the same city that would figure prominently in her books. She spent much of her time as an only child writing poems and short stories. Duncan was also a voracious reader. Her parents, both teachers, possessed a vast literary collection that boasted the pantheon of Black writers: Gwendolyn Brooks. Maya Angelou. Paul Laurence Dunbar. Langston Hughes.

On Saturday mornings, Duncan would listen to the gravelly yaps of Rufus Thomas, a radio personality from the local WDIA station, whose blues broadcasts filled households across Bluff City. The spirited sounds of Memphis Minnie, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, and B.B. King energized an otherwise intellectual upbringing.

Having grown up with the genre, Duncan has made it her mission to preserve blues music by introducing young readers to its brilliant legacy. Her recent picture book, Yellow Dog Blues, which was named a top-ten best illustrated children’s book of 2022 by the New York Times Book Review and The New York Public Library, follows a heartbroken Bo Willie as he voyages along the Mississippi Blues Trail in search of his runaway hound dog. In 2014, Duncan traveled the same trail after receiving a teaching grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to study blues music and the civil rights movement. Dockery Plantation, which influenced musicians like Muddy Waters, and Memphis’s legendary Beale Street, are but a few of the historic sites that Bo Willie passes on his journey. The locations are thoughtfully reimagined with hand-stitched art by Caldecott-winning illustrator Chris Raschka.

The fable of Bo Willie hollering for his hound, laying down a new trail of tears on top of an old one, illuminates one of Duncan’s gifts: she listens for shouts in the void. She heeds Howlin’ Wolf when he asks, in one of her favorite blues records, Why don’t ya hear me cryin’? And then, she may feel urged to write a story on what it was, exactly, that he was howling about. Find her gift in the ghost of Thomas Brooks: My talk ain’t polished. Listen anyway. Find it in the unsung histories she has reclaimed for everyone. To read Duncan’s work is to recognize that the ancestral call is important. But so is our willingness to receive it—and to carry it forth.

In this conversation, Duncan reflects on blues music, book bans, and Southern storytelling. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Illustration from Yellow Dog Blues. Copyright © 2022 by Chris Raschka

Zeniya Cooley: Can you tell me about how you became interested in writing children’s books?

Alice Faye Duncan: I went to library school at UT Knoxville, and I had a professor there who—I was his graduate assistant. He was the instructor for children’s literature, and so when I worked for him, his office was surrounded and filled with children’s picture books. And I would read them. And I was like, I think this is something I would like to do. I tried and I tried. By the time I was twenty-four and had graduated from grad school and was then teaching, I sold my first book.

My mother and father were school teachers who integrated their public school faculties in the late sixties of Memphis, so I grew up in a house full of educators. And when I was in the sixth grade, something really, really interesting happened. We had a guest speaker, Phyllis Tickle. Phyllis Tickle was actually the first religious editor for Publisher’s Weekly. She was responsible for this art program where she would bring artists and writers to school. So I’m in the sixth grade, and Phyllis Tickle comes to our English class, and she brings with her Etheridge Knight. Now Etheridge Knight, he comes into our classroom and he’s looking like every uncle I’ve got. He’s looking like my daddy. He’s looking like my granddaddy. And he proceeds to read his poems and he proceeds to tell us about his literary mother, Gwendolyn Brooks. And he tells us about his publishing life.

I’ve been reading these poets throughout my childhood and never really realized that all poets and all writers were not dead until I see my first living poet, who is Etheridge Knight. And I was like, well, if Etheridge Knight, who is a Black guy who looks like half my family members, can write a book and publish books, I’m going to write books and I’m going to publish books.

I want to get into more of those poets and writers who you mentioned growing up with. What was around your home? What were you reading?

My mother went to Lemoyne-Owen College, which is the Memphis HBCU, and every textbook that my mother had from college, she never sold it back. My father went to Tennessee State. Baby, I don’t remember seeing no textbook of his from nowhere, but he was a voracious reader. He had bookshelves in every room of our house. And one of the writers that my mom had anthologies of and lots of books about was Paul Laurence Dunbar.

Now, as you know, Paul Laurence Dunbar wrote in the African-American vernacular. His poems and Langston’s poems were books that I could easily read, understand, and relate to. I found validation in that because when I was very young, I would write my poems and stories in an African-American vernacular. It affirmed my mother’s tongue because that’s how you speak informally in the house.

You’re from Memphis. What does Memphis mean to you?

Memphis is home. Memphis is love. Memphis is music. Memphis is a place of healing and a place that needs healing.

I want to transition to talking about the blues. Of course, language is important to that, too—expressing yourself within that vernacular and within that voice and spirit. So, what made you want to write about the blues?

On WDIA in Memphis, you had the Saturday morning blues show, and when I was young, I think it was Rufus Thomas who was the morning host of that. So, blues music has always been a part of my life because of the local radio station.

And then during my teaching career, I received a grant to go to Delta State University and to study civil rights and blues music. And so that’s what inspired the idea for Yellow Dog Blues. During the process of that grant, we traveled up and down Highway 61 on what is called the Blues Highway, and we went to a variety of locations that are important to the development of the blues: like Dockery Farms, like Po’ Monkey’s blues joint, which was one of the last plantation blues juke joints before [Willie] Seaberry died, who was the proprietor there. So when I was studying the civil rights movement and studying the blues, I wanted to give American children an appreciation for original American music. If blues music is to survive and if it is to have new creators and composers, you have to introduce it to children. Most times in this day and age, if a child loves the blues, it’s because their mom and their dad introduced it to them. Nobody is really writing books about the blues.

Also, when you look at who supports the blues now, oftentimes it would appear that the great number of blues supporters is not African-American, although they are the originators and creators of it. I want Black children, especially if they’re in the Delta or in the South, to look at blues music as something special, that is rooted and grounded in their culture. I want them to have an interest in its survival. I want them to love it the way that I have come to love it.

And so I was like, Well, how can I do that? And I had a variety of ideas, and most of them were not successful until I came up with the idea of a runaway hound going from Cleveland, Mississippi, and then moving up north toward Memphis.

Alice Faye Duncan photo by Tarrice Love

I noticed that you’ve done heavy research for a lot of your books, like with Memphis, Martin, and the Mountaintop. What was your research like for Yellow Dog Blues?

Well for the most part, the research was the traveling itself and going to the places and experiencing the places. I’ve interviewed a variety of people connected to the Blues Highway. I’ve interviewed Pervis Staples, who is Mavis Staples’s brother. Their dad, Pops Staples, was born and raised on Dockery Farms.

In traveling the Blues Trail, I wanted to make sure that I included three minority cultures that lived in community together [in] the Delta during the thirties and the forties that few people really know about or understand: You had the Chinese sundry store owners, you had Mexican migrant workers, and then you had the Black sharecroppers.

Now when the Mexican migrant workers and the sharecroppers were living in community together [in] the Delta, what they created that has lasted until this very day is the Mississippi hot tamale. And so therefore, in the book, you’ll get Hicks’ Tamales, which is a wink to that fusion food. And then, you also get the Chinese sundry store owner, because what few people understand is that there were a great number of Chinese entrepreneurs that were settled in the Delta.

You mentioned how traveling the Blues Trail was really about that edification. What were you feeling going to those sites and talking to these people?

Blues music is American music, and so out of the crucible of that hard work, labor, [and] the injustice system of sharecropping, we created something that provides solace and a balm of satisfaction to people all around the world. I want Black children from the Delta to understand that they are part of America’s musical heartbeat and that they matter and that they have a voice and that they have a song that they need to keep on singing.

But oftentimes when you go through the Delta, you feel so heartbroken. Cause for me it was like, Do they see and understand their own beauty and how the spirit of their lives and the spirit of who they are has contributed to this great music and this great American tradition? And I want to amplify that with my books. And so it set me on a course to look at Mississippi in a myriad of ways. My next four or five books are all about Mississippi.

A lot of your books mix real-life people, places, and events with fictional details, so I was wondering how you balance fiction and nonfiction?

When I wrote Memphis, Martin, and the Mountaintop, there was not one picture book for children about the assassination of Dr. King. And whenever I broached it to an editor, they always would say, “Oh, but this is such a hard topic—the assassination, the killing, etc.” And so I had to ask myself, Well, how do I broach this very hard, painful subject? How do I broach it in a way that can be interesting, engaging to children, and then end it with a spirit of triumph?

Then I said, Okay, I will make this about a little girl whose dad is a sanitation worker, and ultimately, they overcome and win the strike. When it's something hard, I’m going to add a story. But then there are times, like my [forthcoming] book Traveling Shoes: The Story of Willye White, [where] there was no need to weave some extra story around it because her life in itself was engaging and triumphant, and her spunky personality is something that children will gravitate to.

What topics or themes are your upcoming books tackling?

For June, for Black Music Month, which is also Juneteenth, I have a book called This Train Is Bound for Glory. It’s the Black spiritual about a train that’s on its way to heaven, and the conductor is Black Jesus. Baby, it'’s gonna be wonderful! And then of course, my companion to the Memphis, Martin, and the Mountaintop book is Coretta’s Journey: The Life and Times of Coretta Scott King. And that is for the fall when school starts. The book looks at the lives of Coretta and Martin through cosmic metaphor, dealing with the stars and the planets. But it also [looks] at the calling that is specifically on Coretta’s life—the calling of prophecy, the call to be an activist, and the call to dismantle the patriarchy, the Black patriarchy, of her time.

And then also keeping with the Delta theme and inspiring young children to know that good people have their genesis in the state of Mississippi, I have Traveling Shoes: The Story of Willye White, US Olympian and Long Jump Champion. And so that’s the story of another unsung hero from the Mississippi Delta, who was a five-time Olympian. That’s inspiring. People ought to know. And right from the great state of Mississippi. What do they say? Can any good thing come from Nazareth? Can any good thing come from Mississippi? Absolutely.

Illustration from Yellow Dog Blues. Copyright © 2022 by Chris Raschka

I want Black children from the Delta to understand that they are part of America’s musical heartbeat and that they matter and that they have a voice and that they have a song that they need to keep on singing.

Alice Faye Duncan

Given that your books shed light on Black history, the same history that’s being targeted in schools and libraries across the country, I was wondering if you’ve encountered challenges trying to get these stories to readers?

There was a little situation that happened in Duval [County], Florida, where my book was put on a banned list. And that book was Memphis, Martin, and the Mountaintop. Like, how you gonna ban Dr. King, who comes in the spirit of nonviolence? The school district there put the book on the banned list, and nobody in the district had even read the book. That was discouraging. However, the book banners are not inspiring me to stop writing the books that I feel need to be written for the sake of children all around the world.

Despite the book banners and their opinions, all children need to know about Martin. All children need to know about Coretta. All children need to know about B.B. King. All children need to know about Robert Johnson. All children need to know about Willye B. White.

Willye B. White, here she is from Greenwood, Mississippi, picking cotton starting at the time she’s ten years old until she's a teenager. And then when she turns sixteen, she gets an opportunity to go to Tennessee State to train for summer athletic camp. And in her first visit to Tennessee State for the summer athletic camp, Coach Ed Temple ends up giving her [an] opportunity to try for the Olympics. She makes it, and she wins a silver medal in the long jump. All children need to know about that—how you can use your own strength and determination to will yourself from the cotton field into a life on the international stage.

The reason that I write is that Dr. King, he made it to the mountaintop, and he looked over into the Promised Land. He did not possess the land. And so I’m writing for children in hope that they will be inspired and that they will possess the land.

Could you describe some of your fondest memories of listening to the blues—who you heard, what you heard, and what you felt?

I’ll tell you one of my favorite songs to listen to, and that is Howlin’ Wolf’s “Smokestack Lightning.” That song does something to me. I can’t explain it. If I could resurrect any blues musician and meet them and talk to them, Howlin’ Wolf would be my first choice.

Another thing happened to me the first time I heard Sister Rosetta Tharpe playing and singing “This Train is Bound for Glory.” I was inspired, and so ultimately, I wrote a book about that song that incorporates that song, too. And then when I wanna dance and I wanna feel good, I listen to Koco Taylor’s “Wang Dang Doodle.” That’s my song, baby!

I love how blues song titles are so vivid and descriptive.

Oh, I love it! Another song that has inspired me that I’m writing about: Memphis Minnie has a song [and] most times when you hear it, the title is “When The Saints Go Marching In.” But her version is “When The Saints Go Marching Home.” And when I’m dead and gone, that’s what I want them to play at my funeral, honey. Only play Memphis Minnie’s version of “When the Saints Go Marching Home.”