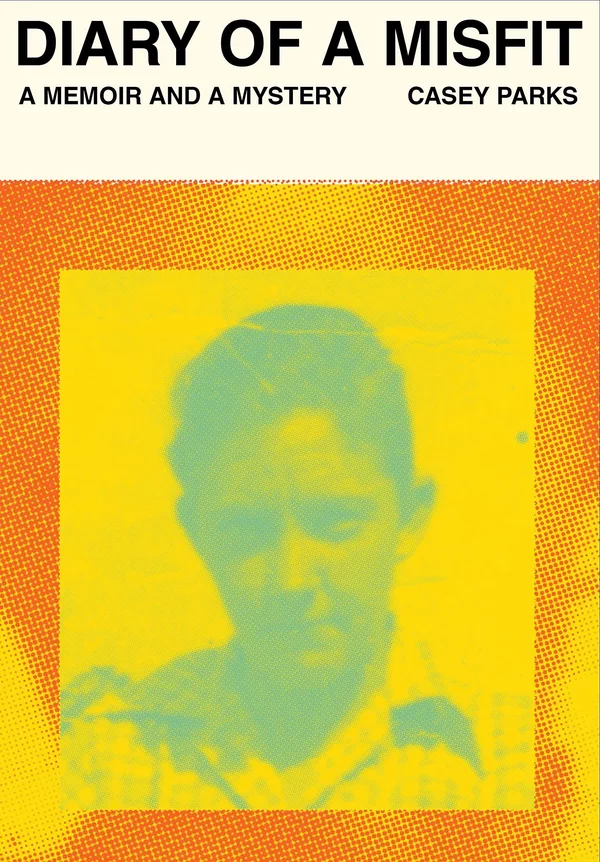

When a Mystery Becomes a Memoir

Casey Parks discusses her book, Diary of a Misfit

By Jason Kyle Howard

Photo by Casey Parks

In the decade plus it took Casey Parks to figure out what to do with the material that became Diary of a Misfit: A Memoir and a Mystery, she started calling it “my albatross.” She had one hell of a story to tell. Back in 2002, her maternal grandmother had dropped a bombshell that gripped Parks, then a student at Millsaps College in Jackson, Mississippi: “I grew up across the street from a woman who lived as a man.” To our contemporary ears, now better trained in the language, politics, and dynamics of gender identity and pronouns, the phrasing is problematic, even offensive. But the news that Roy Hudgins had lived in Delhi, Louisiana with varying degrees of acceptance in the 1960s and 1970s stunned and intrigued Parks. A few years later, after Parks graduated and had moved to Portland, Oregon, where she was working as a local beat reporter, she set out to investigate his life.

Hudgins had died, so Parks turned to his friends and fellow community members in an effort to learn more about his life and experience as a trans man (although, as she points out in the book, using that term to describe Hudgins could be imprecise, as he might not have chosen it for himself). After attempts to turn his story into a podcast and then a documentary faded, Parks slowly began to realize what was missing from the project. There was another narrative tangled up in Hudgins’s, one that she was resistant to telling: her own.

The connection between their narratives had been present, if not obvious, from the beginning. On the same day her grandmother told her about Hudgins, Parks and her mother, Rhonda, were embroiled in a wrenching exchange concerning a secret of her own. A few weeks earlier, Parks had come out as lesbian and her mother had refused to accept her. Rhonda’s reaction had been over the top—she had taken extreme, invasive measures to warn Parks about the certainty of eternal damnation and to monitor her adult daughter’s activities—and that day, everything seemed to come to a head. Her grandmother stepped in: “Rhonda Jean, life is a buffet. Some people eat hot dogs, and some people eat fish. She likes women, and you need to get the fuck over it.”

A journalist to her bones—she now works at the Washington Post following a lengthy stint at the Oregonian—Parks, thirty-nine, was innately resistant to making herself part of the story. But after prodding from a writing mentor, she reimagined the project as a book and experimented with writing about her own life.

The results are striking. Published to uniformly glowing reviews in August 2022, Diary of a Misfit chronicles her efforts to know and understand Hudgins, to interrogate both his past and her own. As the subtitle suggests, there is a mystery involved and Parks, ever the persistent detective, uncovers layers of trauma related to family, fundamentalist Christianity, and identity that redefine her notions of lineage and belonging.

The cast of characters is expansive and populated by Southern originals. Hudgins is rendered with tenderness and care, a mirror to which Parks keeps returning. Her grandmother spins tales and dispenses wisdom while smoking under the carport in her nightgown. There is the young church singer who captures Parks’s fancies; the closeted older lesbian who vows to live openly when her own mother dies; the couple in possession of Hudgins’s diary whose motives concerning his legacy are unclear. All the while, the people of Delhi function as a kind of Greek chorus, commenting on Hudgins’s story and on Parks herself, displaying acceptance as well as overt and covert homophobia and transphobia.

The author’s mother looms over the narrative even when she is not present on the page. Denied a college education after becoming pregnant, Rhonda cleaned houses and cooked for a living, worked at a church, spoke in tongues, and read Tolstoy, all while living with depression, suppressed grief, and an opioid addiction. She is depicted by Parks with a delicate, riveting balance of empathy and accountability.

But the most captivating narrative thread in Diary of a Misfit is Parks’s own. Her dogged pursuit of Hudgins parallels her own physical and emotional journeys. Throughout the book, Parks returns again and again to Louisiana from her home in Portland, searching for Hudgins and something beyond him—something she realizes she must work out in herself. A blend of memoir, reportage, and investigation, Diary of a Misfit reveals the South in its full complexity and establishes Parks as a formidable literary talent.

In this conversation, Parks opens up about what writing Diary of a Misfit demanded she confront, how she captured the contradictions of the South, and what Hudgins’s story can teach us about gender today. The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

DIARY OF A MISFIT is out now on Knopf

JASON KYLE HOWARD: Your search for Roy began as a film. You planned to make a documentary about his life, and so the book traces the conception and the evolution of that project. When did you realize that it needed or wanted to be a book instead?

CASEY PARKS: Well, I actually initially started it as a podcast and then it kind of morphed, but I had worked on it for ten years and had really not gotten anywhere. I had filmed a lot of stuff with my friends and I’d taken off work and tried to write an outline, and we had applied for probably half a dozen grants and I kept getting denied. One of the last times I got denied for a grant, the woman who was administering [it said], “In the movie your main character has to change over the course of the film, and your main character can’t change because he’s dead. So you need a different main character.” I said, “Well, what about my grandmother?” and the woman was like, “Well what about you?” And I was really against that, and that kind of put me in a funk for a while. I just didn’t know what I could do because I could see the woman was right. I’d always call it my albatross because I wanted to do it but I just couldn’t figure [it] out.

So then in 2017, I went to Columbia University to get my master’s. One of my mentors, Andrea Elliott, said, “There’s things you can do in a book that you can’t do in a movie.” And once I started writing [I realized she] was right—you can just add so much context that’s really kind of boring to watch in a documentary. I got newly excited about [the story] because I think the documentary was very much a micro-story. I realized we are in many ways a very typical Southern family. Ours is not the only family that has cotton connections, ours is not the only [family] that has struggled with opioid abuse, ours is not the only family with gay people, we’re not the only ones with this religious experience, and so I think being able to do it as a book just made me start to reenvision it as not just my story or Roy’s story or my grandmother’s story but as Louisiana’s story.

What was your hesitancy about embracing that wider story and your role in it? Was it just a matter of you not thinking that expansively about the project?

I didn’t think I was capable of writing a book when I first started. I really thought of myself as a newspaper reporter who just covers breaking news. And also I think when I first started it I was kind of burnt out on work. When you write for a living, it can sometimes take the joy out of writing a little bit because it’s something you’re selling to live. And so doing videos seemed like fun, like, This isn’t my job, just something I’m doing for fun. But once I started writing I realized there’s a reason I’m a paid writer, not a paid videographer; I’m better at it. But I didn’t really know how to write a book. I’m lucky I got to take this book-writing class, but even with that you’re still kind of on your own. I think my main hesitancy was including myself and also my mother, and the only reason I did that is because that Columbia professor made me try it, and once I did I realized just objectively that it’s better.

I wonder if you felt any tension between your journalism background—which has traditionally discouraged the use of first person, the narrator as a character on the page—and this memoir.

The kind of journalist I am almost demands me to be nothing when I show up to somebody’s house, because I write about a variety of people and I always want [them] to feel like they’re going to get a fair shot with me no matter what side of the aisle they’re on. And that’s a little bit harder once they know everything about me. Really, the way I was able to do the book was to treat myself as if I were a third-person character. I’ve kept a journal since I was a little kid, and I have all my journals all the way back to sixth grade, and so I would go back and just report on myself and be like, OK, what motivated this person? What documents can you [use to] back up your memory? I’ve tried to not just trust my own memory, tried to interview people about me or my experiences, and I think that helped me to do it. It is hard though, and I still feel very weird and vulnerable having it out there.

A big takeaway for me as a reader is your willingness to be candid and vulnerable about your relationship with your mother and the struggles she faced with addiction—to be honest about where she fell short as a parent. And yet you write about her with such love and complexity and empathy. Memoirs can be tricky for families who can feel exposed. Did you feel protective of her, of that relationship, of your family?

When I started writing she was dead, so I did feel many times like I would not have written it like this if she were alive. I really did not think about who would read it, including my own family, and it only came much later that I started to worry about some of that stuff. I think about [how] her friends really lionized her. She’s super charismatic and they all loved her, and she was really great at eliciting sympathy for her various medical issues. And I don’t think that they understood the context—because my parents moved so much, my mom could establish a whole new set of friends and they would have no context for like, Oh, she’s been having a million medical issues since 1982. So I guess I worried about that and hurting those people. That’s probably the people I worried most about.

I didn’t think my father would [read it]. I did ask my dad a lot of questions and ran stuff by him. But I didn’t actually show it to any family members before [publication]. I did my due diligence to fact-check and ask them things, but otherwise I thought, This is my story, and if there was someone that I thought might be hurt, I changed their name. But mostly I [feel] like I am giving some dignity back to my mother. Yes, I reveal all of her struggles, but I feel like I’ve tried to contextualize them, both from a personal standpoint and also from a more macro standpoint. For instance, being able to talk about what the state of the economy was in Louisiana in the early 1980s with the price of oil dropping made me understand my parents a lot better—realizing you’re eighteen, you have a newborn, nobody in Louisiana has a job because it’s dependent on oil, you know, it’s not all your fault. There wasn’t help for her depression. I had grown up thinking we were poor because my parents made bad decisions. And that might somewhat be true, but they also were subjected to economic forces that this state prioritized. I came out of it much less angry at her and much more empathetic toward her. So I didn’t feel like Oh, I’m betraying you by writing this, because I felt like I wanted to give a nuanced portrait of [her].

Part of why I wanted to write this is [that] I had been at Columbia and a lot of my classmates talked about opioid addicts in just this simplistic, two-dimensional way, and it just didn’t square up with my experiences. So to me [writing about her] was almost like bestowing some honor to her to be like, You’re not two-dimensional—you’re amazing, and awful, and complicated and have agency, but you’re a victim.

You show Louisiana and Mississippi as complex places. On the one hand, there’s this homophobic, transphobic, racist, misogynistic streak that is kind of entrenched in white Christian fundamentalism, and then there are people who transcend those stereotypes. You have your characters that you write about, that you reference there. I’m thinking of Ann, who seems to have accepted Roy in the seventies, which defies our notion of time and place. There’s your mother who—although she is grounded in conservative religion and struggles with acceptance, reads her Bible and seems to really take that almost literally—also reads Anna Karenina. I think a lot of people don’t think that about the South, that things like that can coexist. What do you think this book maybe taught you about the South and its people, and what do you hope that it shows readers?

Well, I think I already knew myself that the South wasn’t the stereotype the world paints it to be, so that wasn’t really revealed to me. When I was growing up I didn’t want to leave the South, and I thought the world got it wrong. That was a big hope for me—to show people that the South is not the stereotype that people think it is, that people are much more complicated. Both conservative and liberal people are much more complicated. No one that I met holds one stereotypical view.

[The title] Diary of a Misfit refers to Roy’s journals, but I honestly believe everyone I met identifies that way, like they all felt like the world had cast them as a misfit, and they all wanted to be seen as individual people. And like you said, they held sometimes conflicting beliefs, I mean, sometimes in the same interview they’d say things that went against each other and it would be confusing to me. Journalists like things to be clean and neat so we can hold people a certain way. But actually humans, for the most part, I think are not that way.

I’ll be forty later this year, and I think I left the South [for Portland, Oregon] when I was twenty-two, so I’m kind of like half-and-half in the red part of the country and the blue part of the country, and I really think no one is wholly evil and no one is wholly good. I do think the country might be different if we were all willing to see each other as individual people and not just representative blocks, but it’s easier to get shunted into those blocks.

And there’s context for every story like that, and I think you’re right. That gets lost, it gets dismissed, and it often gets caught up in stereotypes about Southerners and Appalachians and rural folk.

Even one of my mom’s sisters said to me at some point that she thought my mom was like that because she didn’t get enough attention from my grandmother and my grandmother was kind of a hard-ass. [So] I also wanted to figure [out], where does family trauma begin? And you know, my grandmother had her own absent father in some ways, and this big trauma of losing the place where she grew up and losing half her family because of economic forces. I think things get passed down and that doesn’t mean that people are bad people.

A major piece of your story is your reckoning with an upbringing in a fundamentalist church, both as a woman and as a gay woman. As a gay man with a similar background, I’m always curious about people who have shared that experience. From this vantage point, after having lived through that and having written this book, what do you think that upbringing gave you, both in terms of damage it might have inflicted and also gifts you might have received from it?

Well, for starters it gave me stability as a young person. I actually was just talking to my therapist the other day about the youth pastor who’s in the book, who let me live with her, and my therapist was saying it only takes one stable figure in a young person’s life to “save them.” I could’ve turned out really differently. I mean, I grew up poor with a drug-addicted mother in one of the most downtrodden regions of the country. Like, statistically I should not work at the Washington Post. But I probably made it to this fancy job because of the adults at that church who stepped in and provided me stability and who believed in me and kept me in school, and I really can’t overstate how important that was for me.

That said, I think I also grew up just completely afraid to fail and completely afraid that a demon would possess me, and it’s really hard to ever let go of those fears. But all things said, I don’t think I would change having grown up in it, because not only was it stable, it was actually very fun at the time. It was a community, and it felt big and emotional. And going to church teaches you storytelling in a way, because it’s like trying to make meaning and wrest emotion from stories, and there’s a lot to be learned from that. Of course it’s so hard to even extrapolate. I’m sure it broadened my imagination while also scaring me to death.

In writing about Roy, you confront the question of his gender identity on the page and how to refer to him. You write about people’s confusion over which pronouns to use in reference to him, and even your own hesitancy over how he might have chosen to identify had he been alive or lived in our more open and fluid culture. What do you think his story can teach us about gender today?

Good question. I would say first what it can teach us today is that this is not a new phenomenon. There are quite a lot of parents now who are talking about this idea of rapid onset gender dysphoria as if it’s a new concept or a TikTok craze that all these teenagers have formed onto. I don’t think those people have an understanding of the long history of people having some incongruency between their gender identities and what their birth certificates say. And also I guess one thing that really struck me is that a lot of people in Delhi, they are conservative, but they were accepting of Roy. Now, they pitied him, so it might not be the kind of acceptance that liberal activists would really want. I think they did not see him as a threat, they were not angry at him. He told one Pentecostal woman that he felt like he was a man sent to earth in a woman’s body, and that made sense to her. She was like, I haven’t heard of this happening before but Roy really believes that and felt that, and I believe that he felt that. And all of that was possible because Roy’s identity was not a geopolitical issue at that point. Roy was just Roy to them. And so on a personal level they thought, This person is nice, they mow my lawn, they come to church, I have no reason to hate them. People did not understand Roy as a phenomenon. They understood Roy as a person.

That notion—that question, really—of belonging hangs over the book. It’s present in Roy’s story, and it’s present in your narrative as well. You write so movingly about loving the South but not always fitting in, and how you have made a life in Portland but you still miss the South. Have you resolved this tension in your own life of where you belong?

Probably not. But I guess I’m more comfortable with the idea that I belong in both Portland and Louisiana; they can both be mine. I would say culturally, I still feel very connected to the South, but when I fly back to Portland and I see the volcanoes and the green trees, I always have this very clear feeling that I’m home. And I think that’s OK for this to also be my home; it doesn’t take away my Southern-ness. I think I sometimes feel some shame because I feel like I want to live there but don’t feel strong enough or don’t want to give up the easy life I have in Oregon. But I guess I’m fretting about that a little less. And I kept some Southern things from myself for a while when I first moved here—like for many years I refused to listen to country music because the South rejected me, I’m rejecting everything about it. But I listen to country all the time now and I have no shame about it.

I think a lot of us now in the modern world leave home for whatever reason and always feel a bit bifurcated, like some piece of us is gone but you can’t imagine living where you grew up. I think that will become more and more the story as people leave rural areas for big metropolitan centers, [because] that’s just where the jobs are and capitalism, I guess, demands that we all abandon parts of our souls and go live elsewhere and feel a little bit torn up for the rest of our lives.

It makes for good writing though, having that longing for both.

Yearning is always a great basis for good writing.

I’m a big believer that writing a book changes the writer—that you don’t come out the other side quite the same, and so I’m wondering how writing Diary of a Misfit might have changed you.

I don’t think it changed me as a journalist. It completely changed me as a person, and I’m kind of still in the midst of that so it’s hard to explain it. I will try. For most of my adult life I have been a closed-off person. Now that doesn’t mean I would never tell people things about me, because I would tell things I wanted to tell that were dressed up as stories. But I didn’t actually let people really know me, and I didn’t let myself know myself. And I didn’t allow myself to think that my childhood had affected me in any negative ways.

I knew I had had a hard childhood, but I just thought of that as narrative tension, not something that actually shaped how I interact with people. And when my book came out I kind of had a bit of an emotional breakdown, and it just made me realize I’m never going to be able to be happy in my life if I don’t confront a lot of these things and move past it. For a long time I’ve been living in that past, and now I’m trying to figure out, how do I live in the future? And I think I had to write all that down to let go of the past.

This New Year’s Day was the first time I’ve felt hopeful in like five years, so some of that may just also have been having the project hanging over me for so long. I’ve been thinking about this story for twenty years and beating myself up over not finishing it. And now it’s done, and so I’m kind of forced to be like OK, what’s next? Who are you? Your business is out in the world, your project is done. Who do you want to be?