BEAUTIFUL AND BRASH

By David Kirby

Dept. of Georgia Music discoveries

If the official song of the Peach State is “Georgia on My Mind,” the unofficial song of Augusta, that mid-size city on the border with South Carolina, is “It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World.” You hear James Brown’s tortured ballad in stores and art galleries, and you damn sure hear it spooling out of bars when you walk past, even though you suspect it’s not a man’s world at all. Then again, Augusta is a city of deep contradictions, making it a place you want to visit and live in. Neither a derelict Detroit or a blandly affluent Boca Raton, it’s more like a little Chicago, bristling with vitality and paradox.

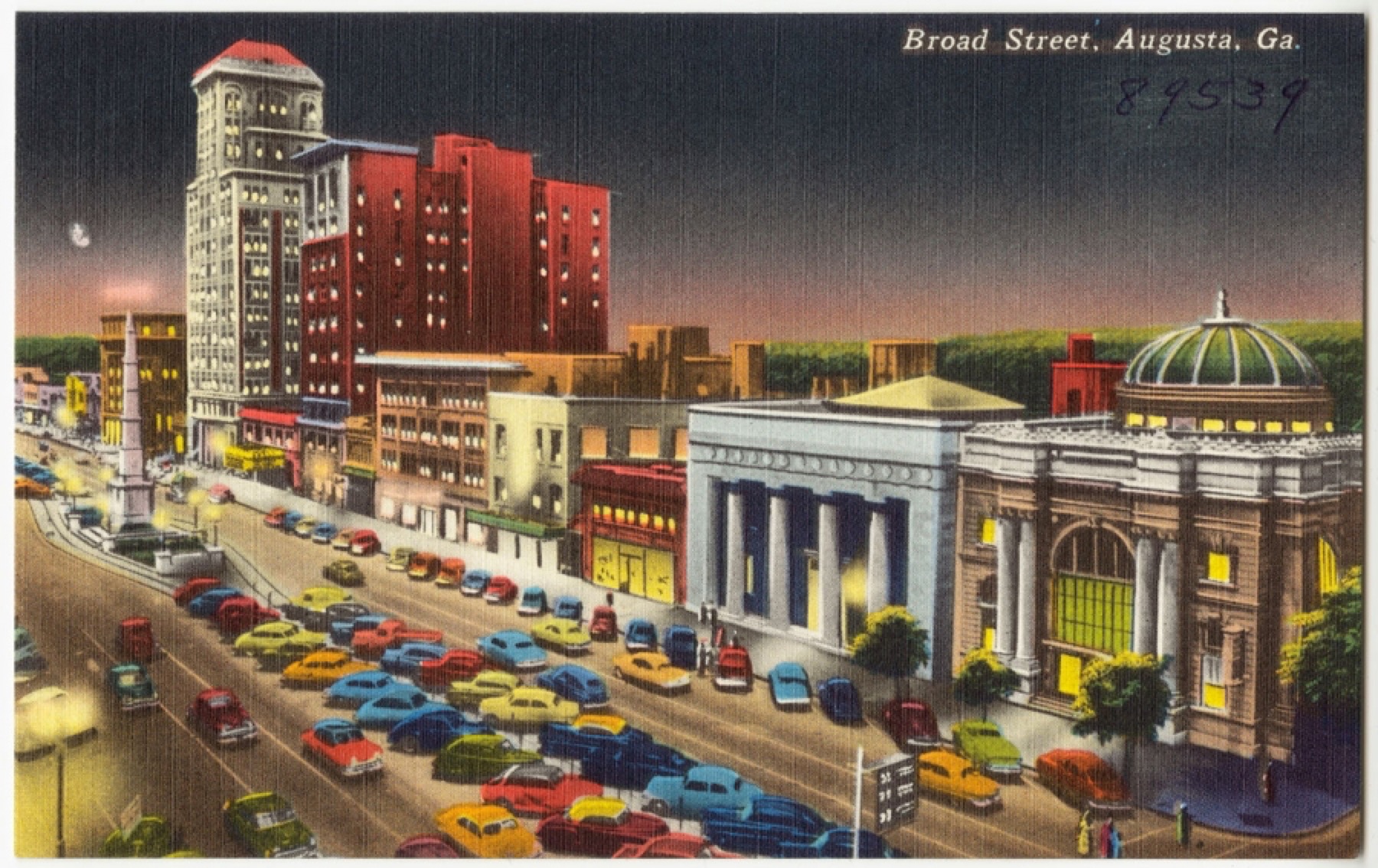

Augusta is “a town with a fascinating case of schizophrenia,” Dorothy Kilgallen wrote in Good Housekeeping in 1953.

It is beautiful with gambrel roofs and lacy ironwork, creeping vines and colonial porticoes; it is brash with jazz brasses and roulette wheels and chuck-a-luck and slot machines and strip-teasers and a sweet-talkin’ disregard for laws that the folks don’t like.

I didn’t see any chuck-a-luck players when I visited last summer, but the gambrel roofs and lacy ironwork are still there. Where there were once jazz brasses there’s now gut-bucket rock & roll, and plenty of it. In fact, that’s why I was in Augusta: to check out the music scene and also to see why a city that is so musically rich doesn’t have the same high profile as Athens and Macon, two other Georgia cities world-renowned for musical greatness.

Augusta, I discovered, has shades of what cultural critic Greil Marcus calls the Old, Weird America—a place populated by peddlers, grifters, doe-eyed schoolmarms, bent cops, hoboes, and riverboat gamblers, where dreams are more important than plans, where your neighbor might be a millionaire tomorrow or an inmate at the razor-wire motel. Sure, the city is ringed with mansions and country-club culture, but when you’re downtown, you can’t go a block without running into a character who looks as though he might be a hustler, a folk artist, a street preacher, or all three.

And presiding over it all is James Brown, a high-voltage live entertainer whose act culminated in a gimmick P. T. Barnum would have loved, the moment when the singer, seemingly near death, is covered with a cape that he casts off as he makes a miraculous return to the stage. A child of the Depression, Brown grew up without money, but then so did a lot of people. There was no credit, and peoples’ wallets were a lot thinner in those days.

No wonder everybody hustled.

My Augusta guide is a bit of a hustler himself. Don “Ramblin’” Rhodes is a reporter for the Augusta Chronicle and a connoisseur of the tidbits other historians tend to overlook. He got his start as a newspaperman writing a gossip column called “The Door Knob” (because the door knob sees everything) for his high school newspaper. Disinterested journalism? Not hardly. “That made people be very nice to me,” he remembers.

It was Rhodes who told me that Tom Thumb was in Augusta in the 1800s, as was Buffalo Bill Cody, Annie Oakley, and John Philip Sousa. John Wilkes Booth’s father and two of his brothers acted in plays in Augusta, though John himself only got as near as the Springer Opera House in Columbus, across the state. More recently, Augusta has boasted, in addition to James Brown, entertainers as diverse as Grammy Award–winning opera soprano Jessye Norman, soul singer Sharon Jones—who recently relocated to the area after years in New York—and rapper Caspar, who lived in Augusta for eleven years before returning to his native Germany. (As it turns out, Rhodes is a fount of knowledge on every aspect of life in the city he loves—the man knows where the best barbecue is, that’s for sure.)

What’s Rhodes’s opinion about why Augusta lags behind Athens and Macon in Georgia’s music-history accounting? The difference, he says, is that both of those cities “have had strong media attention and strong city government support to promote those images,” whereas “Augusta government and tourism leaders have done a terrible job of promoting its music talent.”

As happened elsewhere, downtown Augusta emptied out in the sixties when merchants fled to the malls at the city’s perimeter, though recently, new businesses have replaced the old ones, and now the city center is bustling again with bars and restaurants and hangouts of every type. At the heart of the revival is a behind-kicking live music scene. On any night, you can walk down Broad Street and hear tunes coming out the door of Coco Rubio’s Soul Bar, where Rhodes and I heard a Chicago band called Animal City kick off a set one night with Warren Zevon’s “Poor Poor Pitiful Me.” Just across the street at the Imperial Theater, Ed Turner and his Number 9 band might be doing one of their sold-out shows that cover everybody from Muddy Waters to today’s bluesy rockers. Sky City, Stillwater Taproom, M.A.D. Studios: these and a dozen other honky-tonks are only a few steps away.

In other words, Augusta is a great little music town, regardless of who knows it. And whether it’s jazz brasses or wailing Stratocasters, it’s the music that reminds us that Augusta is just as weird as it was when Dorothy Kilgallen wrote about it more than sixty years ago. The beauty of roots music, and the essence of it (as if “beauty” and “essence” were two different things), is paradox, which brings us back to “It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World.”

You hear this song everywhere in Augusta. But it’s also a song that you ought to hear as a lead-in to CNN news, since it is a man’s world—ask the Taliban, Boko Haram, the Republican Party—yet one in which the men who made and who run it are lost in the wilderness, as the song’s always-surprising last lines go, lost in bitterness. “The world is ugly,” says poet Wallace Stevens, “and the people are sad.” James Brown says the same thing, only in the key of D minor.

A poker-table-size portrait of a young JB looks down on the musicians polishing their chops on the Soul Bar’s tiny bandstand. He’s still the godfather. And if, as Ramblin’ Rhodes says, city leaders take a hush-hush approach to Augusta’s real charms, maybe they’re right to do so. After all, nearby Savannah is a huge tourist destination, but following the notoriety of Paula Deen and the success of movies like Forrest Gump, it’s hard to drive around that town’s picturesque squares the way you could once.

The Old, Weird America is everywhere. It’s damn sure in Augusta, even if this city doesn’t have the reputation some other Georgia cities do. It’s right there in the music. Always was. Always will be.

For more on Augusta, read a profile of Sharon Jones from the Georgia Music issue.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive more in the Dept. of Georgia Music discoveries.