1988.5.60. Untitled, 1973, color photograph. All images © William Eggleston. Gift of William Ferris, University of Mississippi Museum and Historic Houses

COLOR IS EVERYWHERE

By W. Ralph Eubanks

“I want you to know that your parrot has just bitten my mother,” William Eggleston first said to William Ferris. During a trip up to Memphis from Oxford in the 1970s, Ferris had received a spur-of-the-moment invitation to a party at Eggleston’s home. Given that Eggleston, the pioneer color photographer, held a reputation as a loveable eccentric central to the city’s emerging Bohemian community, and that Ferris, the celebrated folklorist, took his Yellowhead parrot, Oggie, with him everywhere, it would follow that a man like Ferris would be welcome at an Eggleston gathering. To play it safe, Ferris left Oggie on a perch outside, at what he thought was a fair distance from the boisterous revelers in the house. Oggie had proven him wrong.

In spite of this awkward introduction, the two shared a few drinks and Eggleston allowed Ferris to look through the prints he kept stacked on top of his Steinway grand piano. Ferris purchased several on the spot—“When I first saw Eggleston’s photographs, it was as if I had never seen a photograph before,” he recently recollected, “I was speechless”—and that night a collection and friendship were born.

Ferris shared this story at the opening of “The Beautiful Mysterious,” an exhibition of more than fifty Eggleston prints donated by Ferris to the University of Mississippi Museum during his long tenure as the director of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture. Throughout the 1980s the two men would often travel throughout Mississippi to photograph together. (Whenever he came to Oxford, Eggleston would stay in the same room at the old Holiday Inn, surrounded by cameras and the elaborate stereo system he traveled with.) Steeped in the folkways of the American South, Ferris understood Eggleston’s work in the context of the photographer’s roots in the Delta, with its complex culture of both artistic genius and racial violence. Eggleston’s 1972 portrait of bluesman Mississippi Fred McDowell lying peacefully in his coffin serves as a counterpoint to the image of Emmett Till caught by Memphis photographer Ernest Withers fifteen years before.

The exhibition is a sort of Faulknerian stream-of-consciousness narrative, moving seamlessly from subject to subject. Tattered orange and red dishtowels on a clothesline, each piece of cloth shot through with holes; a line of railway freight cars shrouded in the evening light of the Mississippi Delta; thin shadows cast on brown cinderblocks below a periwinkle-blue sky. The bohemian and gothic Souths collide in Eggleston’s photographs—his bright colors and distinct perspectives imbue rusting signs and aging buildings with a spiritual, emotional darkness that speaks to a decaying world of an older South fading into suburbia and industrial development. The pictures can be disturbing in their marriage of stark ordinariness and psychic disarray. What James Agee called “the cruel radiance of what is.”

Ferris compared Eggleston with another photographer friend, Agee’s collaborator Walker Evans. “With the grace of a ballet dancer, Eggleston positioned himself for each shot,” he said, whereas “Walker would seek for hours to find the right light and shadows to capture his photographs.” Like Walker, Ferris shot mostly in black and white; sometimes he pointed his camera at Eggleston, perhaps with the folklorist’s impulse to document the creative process. What Ferris remembers most vividly about his many trips with Eggleston is how Eggleston chose his subjects democratically—and only if they provoked an immediate emotional reaction. Perhaps that is why Eggleston says he never takes more than one image of an object. As the exhibition’s curator, novelist Megan Abbott, notes, Eggleston doesn’t see much difference between people and objects. It is all one long body of work.

Thirty years have come and gone since their house party meeting, but the two remain close and continue to spend time together. On their most recent visit, Ferris asked Eggleston why he decided to photograph in color. The answer was simple. “Color is everywhere,” Eggleston said, “even in the black hole of space.”

The Beautiful Mysterious: The Extraordinary Gaze of William Eggleston. September 13, 2016–January 14, 2017. The University of Mississippi Museum.

He was a great mentor, and I learned as much from him as I did from any teacher at the Academy. We rode around in the late afternoon light in Memphis and its environs, where I observed those things he thought worth photographing (pretty much everything!). It was an education in how to look at the world and take away a little piece of it, and for that I’ll always be grateful. I later moved to New York City, where Bill had the first color show at the Museum of Modern Art (Photographs by William Eggleston, 1976). Not everybody quite understood the work then, but later they did.

—Maude Schuyler Clay, photographer, author, and cousin of William Eggleston

Standing before these photos, we are never mere observers. We experience them. We feel them. We close our eyes and still see them. We’re forever seeing them. Look at an Eggleston photograph once and you are forever altered. Suddenly, you are in it. It is in you.

—Megan Abbott, novelist and guest curator of The Beautiful Mysterious: The Extraordinary Gaze of William Eggleston at the University of Mississippi Museum

1982. 1.3. Untitled, 1972. Vintage Dye Transfer

1988. 5.2. A Good View, 1981, color photograph

1988. 5.3. Oh No, 1981, color photograph

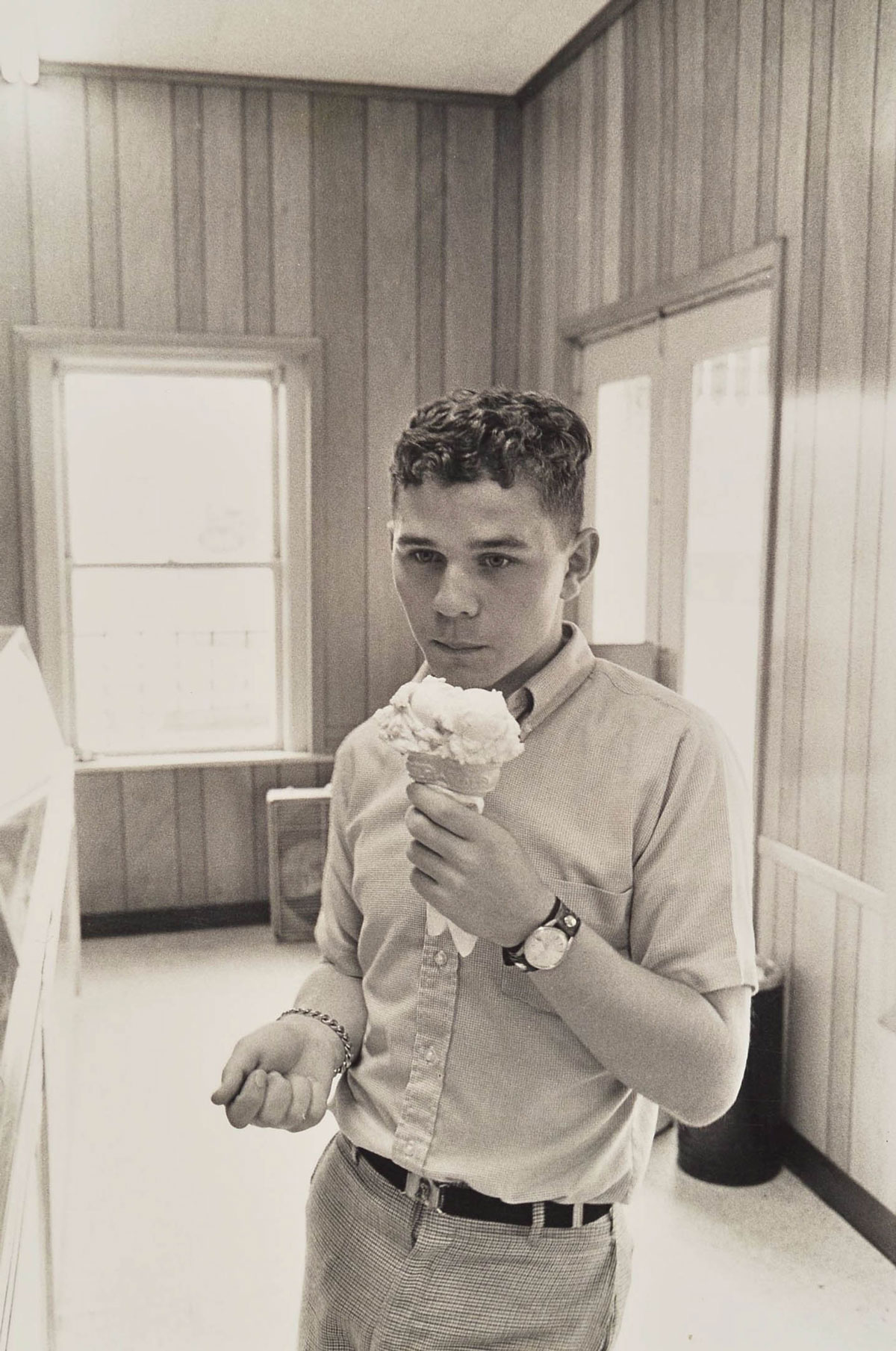

1988. 5.54. Untitled, 1962, black and white photograph

1988. 5.54. Untitled, 1962, black and white photograph

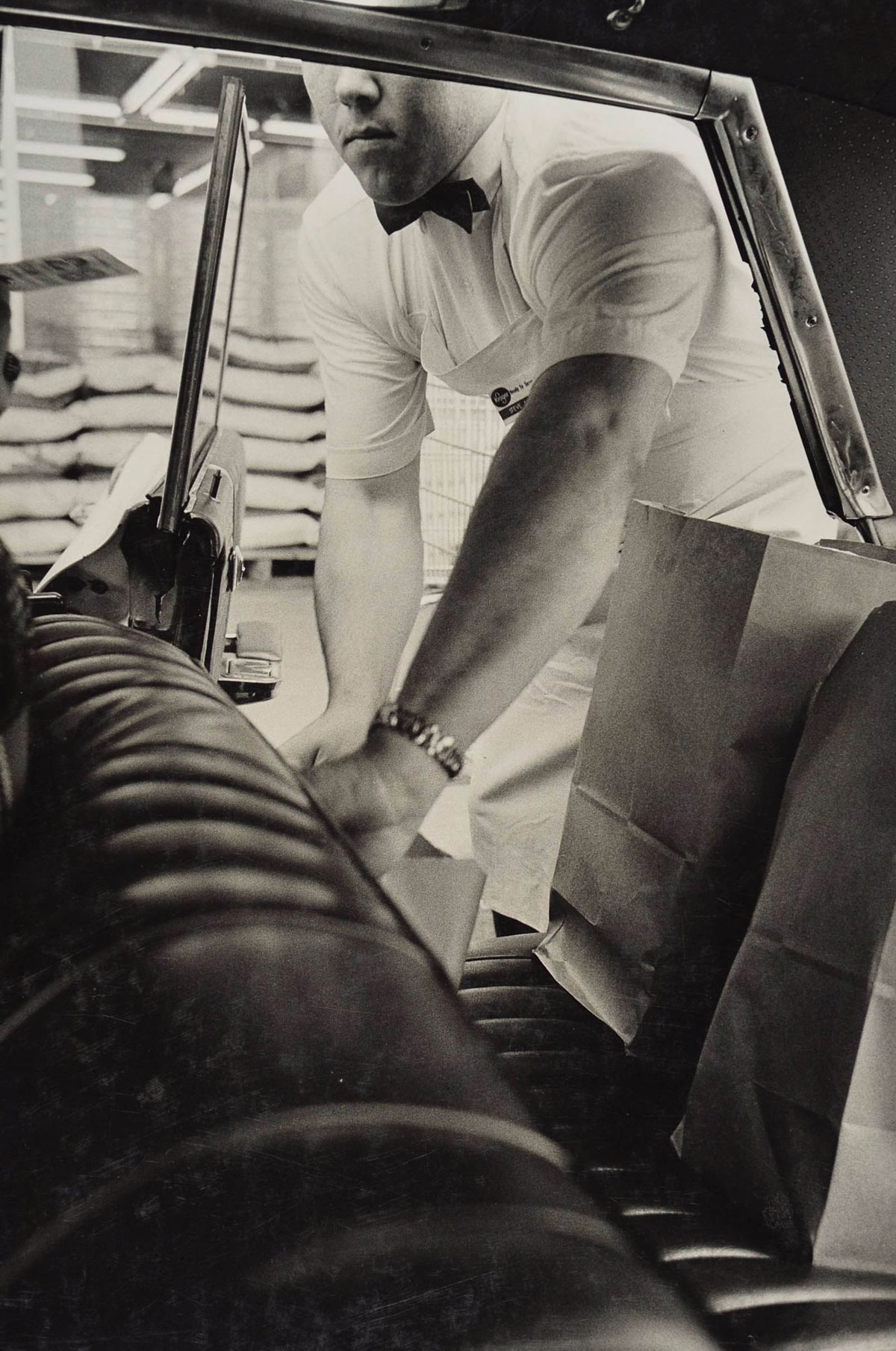

1988. 5.57. Untitled, 1964, black and white photograph

1988. 5.60. Untitled, 1973, color photograph

1988. 5.7. Untitled (Door with Dixie), 1981, color photograph