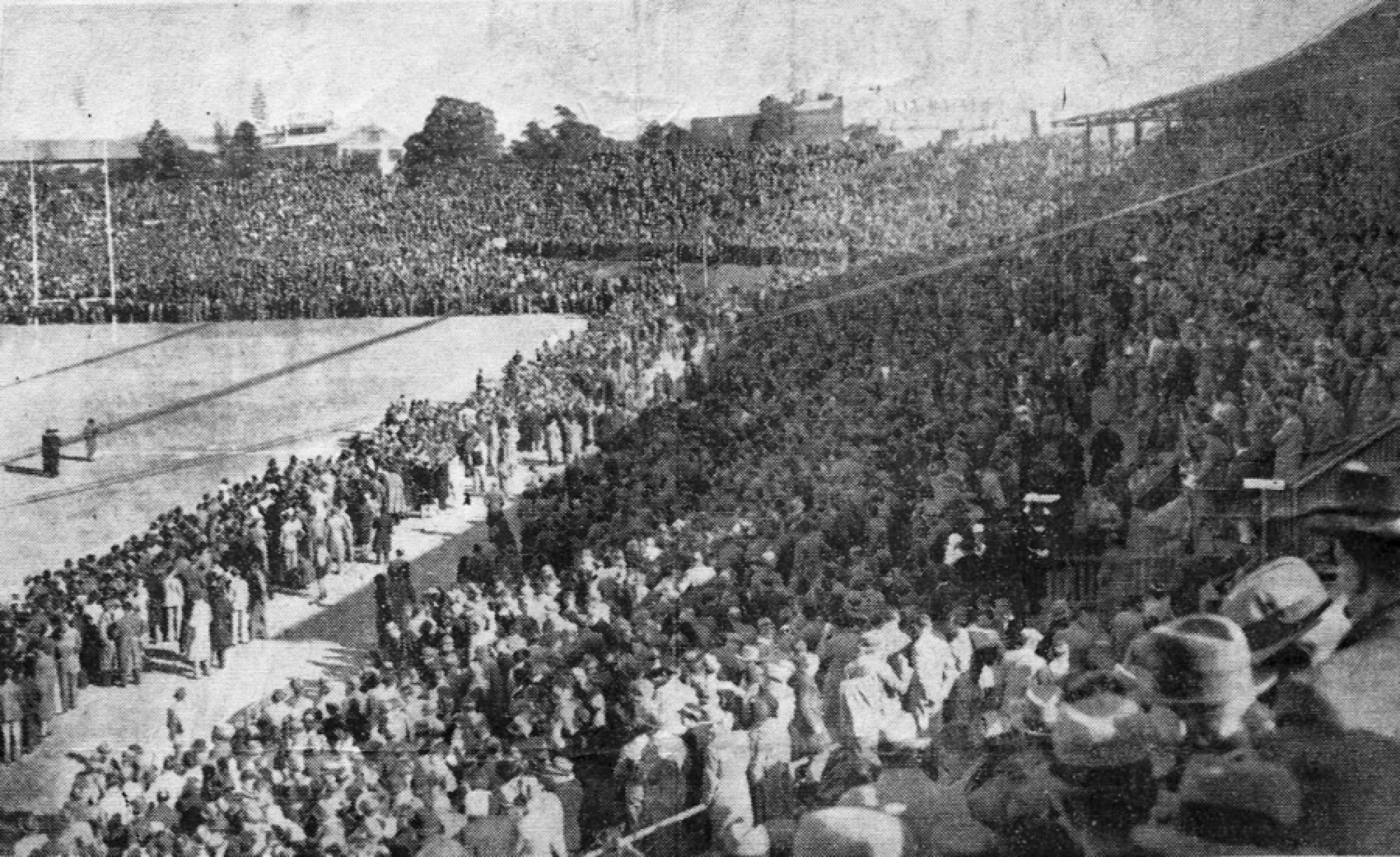

Ellis Park Stadium, 1938, South Africa v. British Lions, from Wikimedia Commons

CONSEQUENCES FOR A THIEF

By Meghan Tear Plummer

Mzansi South

South Africa’s spring feels much like America’s fall. I think of a graph with a sine and cosine curve; they mirror each other, and so are completely opposite, but at certain, single points, they are the identical. The weather now, for instance; a traffic light suspended above a street instead of on a post in the median; a lantana bush in bloom against a wooden fence—these are all places where such lines cross, where South Africa becomes indistinguishable from home.

We went to a Super Rugby match to see the Lions play. Ellis Park is in downtown Johannesburg, surrounded by the iconic buildings of the city’s skyline: Ponte City and the Hillbrow Tower. Despite its metropolitan setting, the sea of red jerseys and the concrete courtyards that funneled toward high gates reminded me of game days at the University of Alabama, where my husband and I attended graduate school. We lived in Tuscaloosa until we moved to Johannesburg.

“Keep your purse closed,” one of our friends reminded me before we went to the stadium. “A lot of phones get stolen.”

We sat in the top deck behind the try zone, and it was easy to get wrapped up in the match. Many of the players on the field were also Springboks—that is, select members of South Africa’s national team—and suddenly the world of South African sports seemed so intimate. It made me think again of Alabama, where Crimson Tide football players ended up as students in our classrooms. Nostalgia overtook me, and I thought of Tuscaloosa game days, the walk between our apartment and the stadium, how we’d stop at our favorite bar on the way home. Maybe rugby was a South African subculture I could really get into; maybe it would help me feel more grounded here. When “Sweet Home Alabama” came over the stadium speakers, it felt like more than just a coincidence.

But when the match ended, the spell was broken. We did go to a bar, but it was a strange warehouse of one inside the stadium itself, clearly open only on match days. Behind its counter, wrappings from pallets of Castle Light and cans of tonic littered the ground. Even the ice came from somewhere else, shoveled out of plastic bags into disposable cups pulled from tall cardboard boxes. The bar’s temporary nature made it feel so flimsy. This place wasn’t part of anyone’s traditions. “Sweet Home Alabama” came on again, and now it felt like a cruel joke. It wasn’t cosmic—it was just a song on a recycled playlist.

The women’s bathroom was at the end of a hallway built from plywood partitions painted white, and I stood in a corner just beyond the door, trying to find that balance between crying enough to feel better but not so much that we’d have to go home, where I’d likely shut myself in the bathroom and look at next-day flights to the U.S.

Other women paid no attention, and I thought they were merciful in ignoring me, until a security guard approached and put a hand on my shoulder and then on my cheek.

“Why are you crying?” she asked.

I told her it was because I wasn’t from here and I was very homesick, and she pulled me into a hug and I cried harder at her kindness. I could tell from her accent that she, too, was from somewhere else.

By the time we left the bar, it was dark out. We hailed an Uber from inside the stadium to avoid having our phones on display outside of it, and the driver asked us to meet him at a Shell station across the road so he didn’t have to stop in traffic.

It wasn’t a particularly large gas station, but it was full of people, inside and in the parking lot. The fifteen-passenger vans here, known as taxis, were parked at the pumps with no apparent desire to fill up, and other cars maneuvered around them as the taxi drivers chatted or went inside for food. Other Uber drivers waited, hazards flashing, and people passed on the sidewalk before us wearing their red jerseys from the match.

A young man, perhaps in his mid-twenties, was running hard away from the stadium, along the sidewalk we stood on, and other men were gaining on him. They caught him just in front of us, pushed him to the ground, and began to beat the young man with canes and sticks. We were stunned, unmoving, until the young man cried out in pain. I yelled for them to stop.

A few of the men did stop, looking up in confusion, which was enough for the young man to stand and run toward the Shell station. His attackers did not follow or call after him but only watched, casually tapping their sticks against their thighs. I noticed then that their shirts said ELLIS PARK SECURITY, and suddenly, I didn’t know if calling out had been right or wrong; private security in South Africa fills the roles that an overworked police force cannot. Everyone else seemed as confused as I was, as ambivalent.

One of the security guards approached me. “This man was stealing people’s phones,” he told me, not unkindly. “It’s you we want to protect.”

“I know. Thank you. I know you’re doing your job. I’m sorry,” I told him, touching his arm. “It’s just hard to watch.”

At that moment, the young man passed us again. Perhaps he thought the security guards had disbanded, but they hadn’t, and they pushed him to the ground again and resumed their beating. But knowing the men were security guards, I saw things differently. I saw that the men avoided the young man’s face, and it was only with whips that they beat him. No one kicked or punched him. There was no anger in the men’s faces. The more I watched, the more rules of engagement I could detect.

“This is barbaric,” someone said behind me, and I smarted at the word. I didn’t like what I saw, but “barbaric” implied senseless violence, and this wasn’t barbaric. Someone had done something wrong, he had been caught, and now his punishment was being meted out—and according to observable rules.

The young man was allowed to stand, and one of the security guards held his arm to prevent him running again. The group made toward the stadium, and I remembered a tour of Johannesburg’s Hillbrow neighborhood that we’d taken my parents on during their visit in April. Our guide had explained how the rule “snitches get stitches” worked in the community. Often crimes went unreported and unpunished because if someone led the police to the perpetrator, then the perpetrator, once out of jail, would come for those who’d turned them in. What we’d seen was an unreported crime, but it wasn’t unpunished.

I tried to imagine the American analog of what I had witnessed that night. There would have been police instead of security guards, batons instead of canes. There would have been fees the man could not afford to pay, perhaps time in a prison where he’d experience violence that had nothing to do with his original crime.

“Be careful you’re not romanticizing it,” my husband said a few days later as we talked through the experience. I knew what he meant, but it made me feel lonely that he and I did not agree; I thought this could be the moment when my beliefs allied with a South African’s, but it wasn’t. When I told my American friends and family about the men punishing the young thief, I knew they only envisioned a man being beaten in the street.

The truth is that I romanticize a lot of what I see—what passes outside my car window and rugby matches and even the consequences for a thief—because I’m always trying to get back to that individual, singular point where my experiences here are identical as at home, where what I see is something I recognize. Instead, I find I don’t belong in either place.

“Mzansi South” is a part of our weekly story series, The By and By.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.