Photo by Aral Tasher on Unsplash

Doing Nothing

By Julien Baker

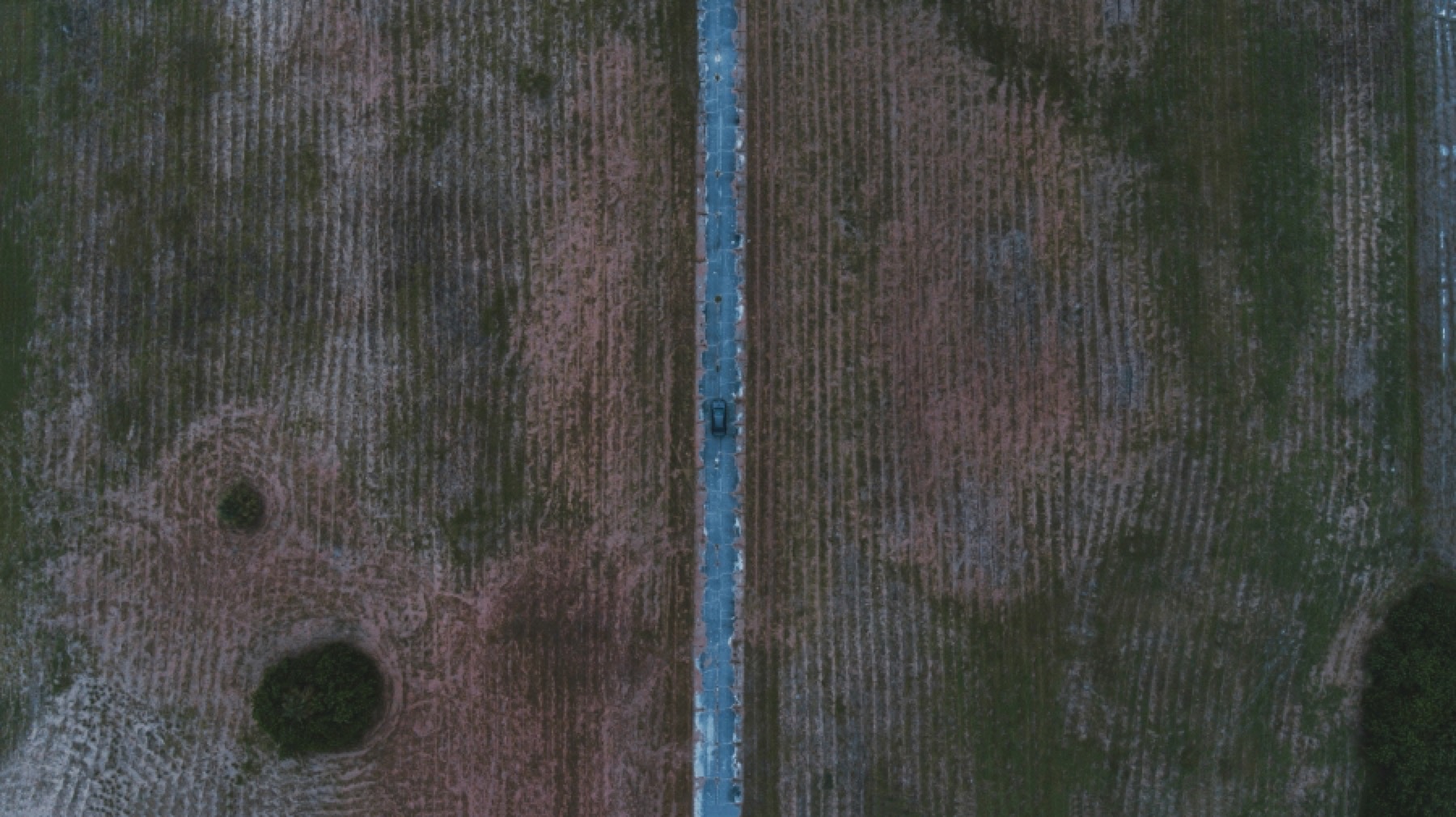

West Tennessee is flat, barren earth. In winter, everything dies and turns the same gray-brown as the sky, both sides of the horizon meeting in a blur of beige foliage and ruddy clouds. On a drive home for the holidays after three months of consecutive absence on tour, I stared out the windshield trying to calculate how many cumulative miles I’ve spent on this three-hundred-mile strip of road and picture my tires carving grooves into the asphalt of Interstate 40.

My mother would take this route on our countless drives from Memphis to Smithville to visit her parents in East Tennessee. Often it was just the two of us, my mother, piloting our family’s modest sedan through hills and blasted rock, and me, with the backseat to myself, becoming familiar with the mountainous landscape through the porthole of my window. Their house was modest, decorated in the muted taste of rural American South, with floral print furniture and collectible plates bearing airbrushed portraits of Elvis. It felt as dull as all adult homes must feel to children, and so I’d kill time in the yard building entire worlds out of old water hoses and discarded tires that littered the creek, the neighbor’s tiny makeshift landfill. When it was time to go, I brought the worlds with me. Four hours was an eternity to a child, and I spent it looking out the window, lost in another plane, debriefing missions and inventing histories of rivaling nations whose unstable foreign policy posed a dire threat to the safety of my tree fort.

My life is still comprised of these moments. Being a touring musician is mostly travel; in between the minutes of performance stretch weeks of time spent in transit, on to the next show in the next town as a View-Master slideshow of gas stations whips by. That forced idleness creates so much time to Do Nothing: to say nothing, to sit and think, observe and digest. In fact, having nothing to do for long enough makes you realize that Doing Nothing is actually a fruitful activity.

To a culture of productivity, unscheduled time is a cardinal sin. Idle time is discouraged because it is often collapsed with laziness. We fear that stillness indicates stagnation, as if inaction is an opportunity cost to possible joy or success. We fear silence most of all, believing it signifies emptiness, and we rush to fill it with stimulation and communication, publicly cataloging our thoughts and memories as evidence that we are alive. But there is value in unoccupied time, empty space, and silence. Doing things without a purpose gives us a chance to consider the purposes of things around us.

Lack and need cultivate the power to imbue existing objects with new function and meaning. In the absence of the real thing, we invent solutions where unusual things take on new potential. The mental alchemy of childhood that turns snapped branches into daggers becomes the ability to transform a fire escape into a dryer, cinder blocks and plywood into a bed. Imagination gives us the optimism to uncover usefulness in what is otherwise discarded as the ugly or insignificant. From the overpass behind the neighborhood where I grew up, I remember watching the freight trains covered in spray paint slither by and looking on with awe and interest while cars of cartoonish pastel on rusted metal canvas passed. I was confused when someone’s parents told me that those things were ugly; until then I thought it was just innovative. The mind supplies beauty in a world that is often not beautiful to make it tolerable, then it becomes truly believably beautiful, or we realize the things that already were.

This capability to discover extraordinary significance in the common is exercised in scarcity of stimulation. To glean knowledge from our experience we need time to be educated through humble observation. If we are always keeping silence and stillness at bay, we can never find those things embedded in our world, we drown them out.

On the drive to Memphis, the exercise of transmuting the usual into the remarkable was still ongoing. The horizon flattened into a gradually less stimulating plane, and I began to eye other motorists, naming the drivers of semitrucks and sports cars, entertaining myself by imagining scenarios of their journey. Alone in the car with no noise except sagging duct tape on my headlight flapping against the bumper, I waded into the familiar blankness of idle thought. Today I want no sound, no music at all.

It was devastating to find how much I enjoy quiet. For a person whose life is consumed by music, it felt like blasphemy. The first time that I sat down to play guitar and nothing came out, I was terrified. I had thoughts and thoughts and thoughts but the prospect of communicating them was impossible. Memories, feelings, opinions, fears, plans, all the raw ore of the mind heaped up around me, yet I had nothing to say. As my world expanded, I shrank. I saw in the eyes of people I’ve encountered through years of shows, who I’ve met on a bus or at the grocery store, whole lives. Inundated with the closeness and realness of others, my puny idea of the self shriveled up, withered when confronted with the awareness of everything else that is already there. Suddenly art was a feeble offering. To absorb these things was an undertaking enough, and I had no idea what a response could possibly look like. I did not understand the worth in silence or the action in listening.

Our culture is one of constant engagement and documentation. The infinite connectivity of social media presents us with endless access to information, and gives us the power to respond. We are urged to share, prompted to comment, to participate. Eagerness for involvement is not a bad thing. Neither is outspokenness, nor conviction. Constant engagement is a far better alternative than the detached apathy which tacitly endorses a status quo of inequality and oppression. But in a political landscape that demands representation and visibility, listening is as important as speaking. Silence can be powerful, reverent. So much of our social dialogue is about who is permitted to take up space and where, what structures are preventing the marginalized from existing peacefully within public space. Carving out that space for others to inhabit it is not passive or apolitical. It is the active work of seeing and hearing each other.

When we listen to others, we learn as much of ourselves as we do of the other person. By listening to others’ stories we learn how to tell our own stories with more reverence, with more awareness and perspective, how to situate ourselves in the universal character-cast of human beings. Playing music for a living makes creating and sharing thoughts central to my existence, and it affords me an atypical platform to promote things that are important to me. Yet ironically, what having a microphone has taught me is how much I have to learn from listening.

When I began writing this essay, I couldn’t find any piece of wisdom or anecdote from my life that seemed absolutely crucial or profound when measured against the oceans of other human experience. If I felt I couldn’t offer something meaningful, well, maybe there is something to be learned of having nothing to offer. I choose to start trying to document what is already meaningful. There is a vital lesson in allowing yourself to be silenced.

“Getting Out of the Way” is a part of our weekly story series, The By and By.