DREAM OF A HOUSE

A Dispatch from the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University

By Alex Harris, Margaret Sartor, and Reynolds Price

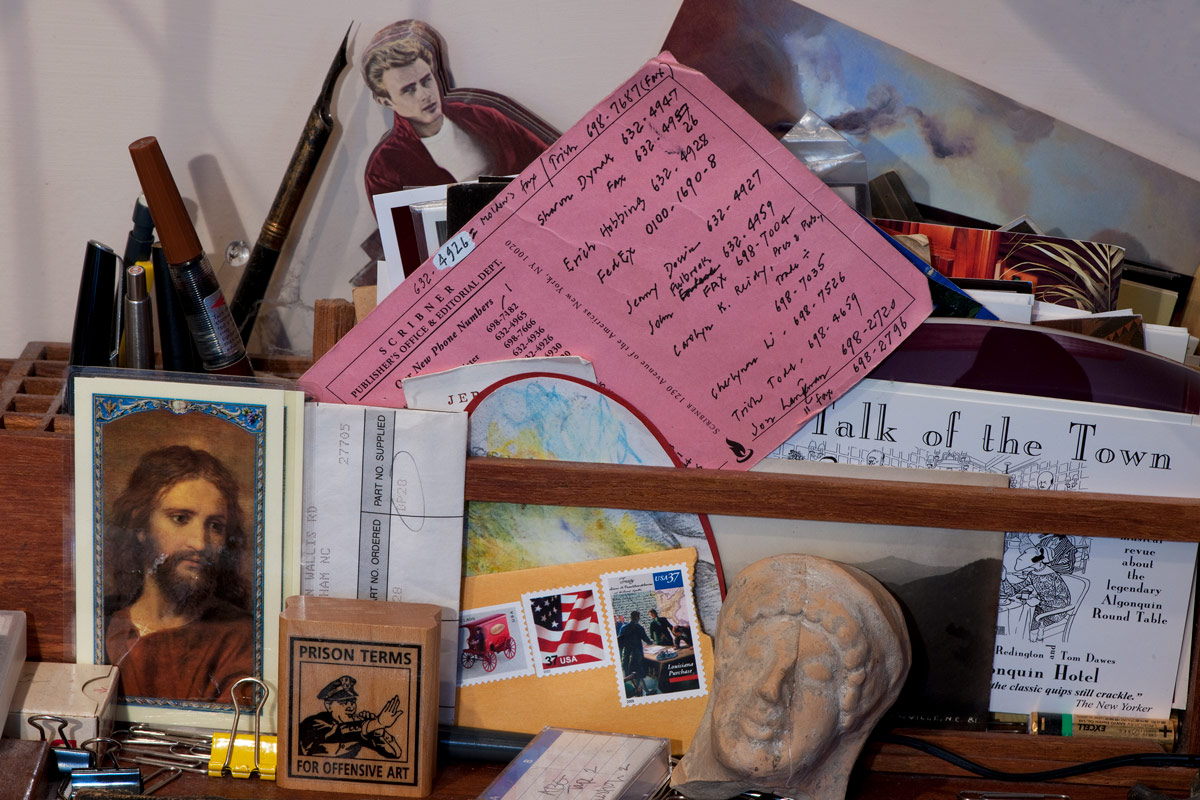

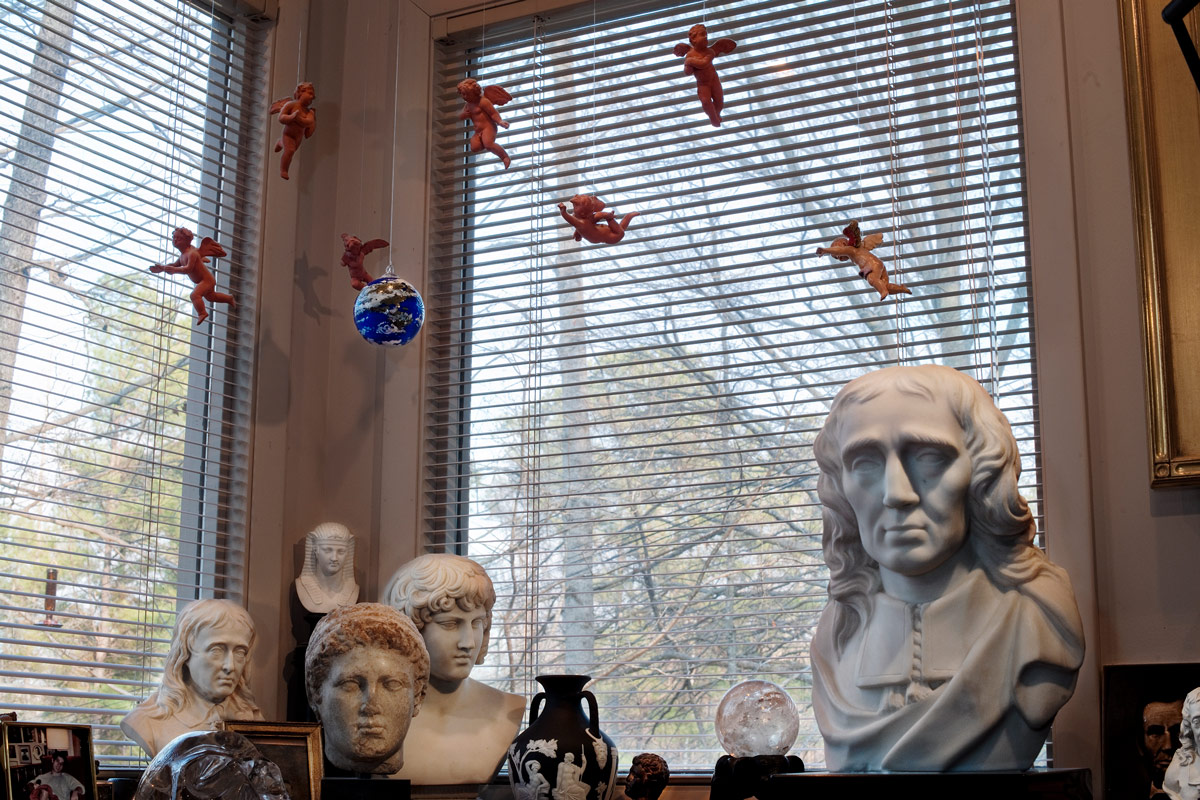

Reynolds Price’s house, Durham, North Carolina, 2011. Photograph by Alex Harris from “Dream of a House: The Passions and Preoccupations of Reynolds Price.” To see more photographs and learn more about the book, visit alex-harris.com

A couple of years ago, Alex Harris and Margaret Sartor, both photographers and writers and longtime colleagues at the Center for Documentary Studies (CDS), mentioned a book that they were working on about the house, and therefore the mind, of renowned Southern writer Reynolds Price. We were immediately intrigued.

Reynolds was an intimate friend of Alex and Margaret’s and a committed and early supporter of CDS, which Alex cofounded in 1989. Reynolds, a beloved teacher at Duke University for more than fifty years, lived in Durham, North Carolina, in a modest brick house surrounded by trees and quiet. The exterior of the house revealed little about its vibrant, sometimes nearly ecstatic, interior.

After Reynolds died in 2011, Alex was asked by the Price family and Duke University to photograph the house before it was sold and the artwork as a living collection disassembled. Margaret and Alex then began reading, and re-reading, Reynolds’s work; they have meticulously, and lovingly, selected excerpts from his poems and writings that interweave with and further amplify the effect and meaning of the images.

Dream of a House: The Passions and Preoccupations of Reynolds Price, published by George F. Thompson and the Center for Documentary Studies, will be available this month. An exhibition of selected words and images is currently on view in Duke’s Rubenstein Library Photography Gallery.

As James Taylor puts it, “These images of our dear friend and native son, Reynolds Price, are precious reminders of a lovely life, fully lived and generously shared with those of us lucky enough to have known him. Every page summons the memory of that indomitable spirit and wry conspiratorial humor. How could he be both compassionate and wicked? It is even good to miss him.”

So it is with great delight that we share an excerpt from Margaret Sartor’s afterword for the book, with selections of Alex Harris’s photos and Reynolds Price’s words, as our newest dispatch for The By and By.

—Alexa Dilworth, CDS Publishing and Awards Director

Painting of Reynolds Price (detail) by Will Wilson, photograph by Alex Harris

I’m perfectly prepared to believe that the world is not only more complicated than we know but than it is ever possible for us to know, simply because we are limited as human beings by the capacities of our sense organs. There could be incredible visual phenomena actually occurring in this room right now which you and I simply can’t see—no doubt they are occurring—because our retinas are only capable of responding to a very short portion of the spectrum of light. The room could be filled with angels, you know, dancing nude—and we wouldn’t know it.

—Reynolds Price, from Conversations with Reynolds Price

If Alex and I understood in outline the truths expressed in Dream of a House before knowing Reynolds Price, it was Reynolds who, over the years, painted in the colors, with shade and nuance.

My friendship with Reynolds Price began in the mid-1980s, soon after Alex and I married and not long after Reynolds was confined to a wheelchair as a result of radiation treatment he received for spinal cancer. I never knew Reynolds as a physically upright person. Yet, of all the people I have known, he is one whose intellectual and artistic stature was monumentally impressive. Yes, he could dominate a table or a room, but he made good use of the platform—storyteller extraordinaire, erudite but never elitist, a wise man, generous of heart and in spirit, if not always in sharing the limelight.

As it turns out, Alex and I are good at appreciating brilliance. Whether in cooks or carpenters, artists or academics, or the everyday banter of a comedic bartender, we are awed by originality, aptitude, and exceptional optimism. We can agree to overlook the human flaws that co-exist with such traits. After all, a certain amount of arrogance tends to come with the territory. And if brilliance is tempered with self-awareness and leavened by a sense of humor, we relish the role of audience. Our friend Reynolds Price was unquestionably brilliant. He was handsome and charming and gifted, and he knew it. He was also profoundly sensitive, or maybe it was sensitively profound, or both, and it showed. All the time.

When I first got to know him, I was in my mid-twenties and more than a little frightened by the immensity of my hopes and dreams for a fulfilling life. Reynolds was in his mid-fifties, around the age I am now. Reynolds, by that time, had achieved tremendous success, but he had endured losses and survived both. Then, he survived cancer. He comprehended to his core the essential importance of home and family, the necessity of reliable friendship, how in every breath we should welcome and acknowledge the unbidden power of grace. But early on he also began to recognize hard facts that most of us resist for years, if not decades or lifetimes: That living well is a complicated and conscious endeavor, that the so-called trivialities of life can serve as an antidote to that which feels too serious to bear, that relationships of any kind require both commitment and compromise, and that a partnership in love often boils down to the granting and honoring (by people of sound mind) of the right to use and be made use of by another.

He was, as everyone knew, intolerant of prejudice in any form, but he was also old-fashioned, hardwired to certain Southern rituals, and not just in his religious beliefs. For whatever reasons, none of them having to do with his respect for me or my work, he always referred to Alex and me together as “The Harrises,” though he knew I had not assumed Alex’s surname. And once, introducing me to a packed room for a reading from my memoir, Miss American Pie, he referred to me as a “swizzle stick of a girl.” (I was thin, but I was also over forty.) It was the kind of joke someone from my family might make, and it delighted me. This in itself was a gift because, in the simplest terms, Reynolds Price showed me that being Southern, irrevocably religious, and overly polite, with an uncontained curiosity for people, their stories, and an appetite for deep-fried food, was not synonymous with a lack of intellectual rigor. The picture Reynolds painted as a way to live was refreshingly honest and charitable with a healthy dose of hedonism. It still looks good to me.

The pictures are images of household gods, I suppose. Images of what I have loved and love and worship—worship in the sense of offering my life and work to them. The pictures are of members of my family—some of whom I never knew, who died before I was born—and of friends who have caused my life and my work. They are here, and here in such numbers, for the sake of my present and future work, not for the sake of nostalgia, not as souvenirs of a lifeless past. That is an aspect of my own work, as it is of almost every artist’s work, which is little understood by people who are not themselves artists—the extent to which any work of art, especially verbal art, is a private communication between the artist and a small audience, often as small as one.

—Reynolds Price, from Conversations with Reynolds Price

So, in 2011, we lost him. I’m still sad about that. Sad that I didn’t get around to sending him that postcard of Vivian Leigh I purchased in a bookstore in L.A., sorry I didn’t see him during those last, excruciatingly painful months of his life. But grateful that, as Alex tells in his essay in Dream of House, we found him again in a shared dream. That is, on the same night, about six months after he died, Reynolds appeared in each of our dreams. In both dreams, Reynolds was younger, slimmer, and seemed content but, in different ways, was having difficulty, struggling to see. When I think of that night, it is more as a visitation than a dream. The conversations between Alex and me that followed were the beginning of this joint project. And now there is this book, which, we hope, opens other people’s eyes to the richness of life that occupied and preoccupied Reynolds Price. This book, our loving farewell, is not compensation for the loss we feel, but it is some consolation, the best we know how to offer to him, to each other, and to all of you who have now shared in his world.

A need to tell and hear stories is essential to the species Homo sapiens—second in necessity apparently after nourishment and before love and shelter. Millions survive without love or home, almost none in silence; the opposite of silence leads quickly to narrative, and the sound of the story is the dominant sound of our lives, from the small accounts of our days’ events to the vast incommunicable constructs of psychopaths.

—Reynolds Price, from A Palpable God

In 2011, the Price family asked Alex to make photographs of Reynolds’s home after he died, before the inevitable process of dismantling had begun. Later, in 2013, after reading and searching through Reynolds’s published work and interviews, Alex and I together began to pick out quotes and match them with his photographs, to see what kind of chemistry occurred. Eventually, we created a sequence of images and words, at first unclear in purpose but with a rhythm, a heartbeat. In the next draft, Reynolds’s voice gained clarity and resonance, the arc of his story was dense but also more refined. In final revisions, with the excellent feedback and expert suggestions of our editors Alexa Dilworth and George F. Thompson, Alex and I polished it smooth and, it seemed to us, a kind of diamond emerged, something clear and true. Or that is what we hope. We know for certain that it is true to the Reynolds Price we knew.

—Margaret Sartor, from Dream of a House: The Passions and Preoccupations of Reynolds Price

How does a newborn child learn the three indispensable human skills he is born without? How does he learn to live, love, and die? How do we learn to depend emotionally and spiritually on others and to trust them with our lives? How do we learn the few but vital ways to honor other creatures and delight in their presence? And how do we learn to bear, use and transmit that knowledge through the span of a life and then to relinquish it?

—Reynolds Price, from Clear Pictures

This installment of The By and By is curated by the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University (CDS). CDS is dedicated to documentary expression and its role in creating a more just society. A nonprofit affiliate of Duke University, CDS teaches, produces, and presents the documentary arts across a full range of media—photography, audio, film, writing, experimental and new media—for students and audiences of all ages. CDS is renowned for innovative undergraduate, graduate, and continuing education classes; the Full Frame Documentary Film Festival; curated exhibitions; international prizes; award-winning books; radio programs and a podcast; and groundbreaking projects. For more information, visit the CDS website.