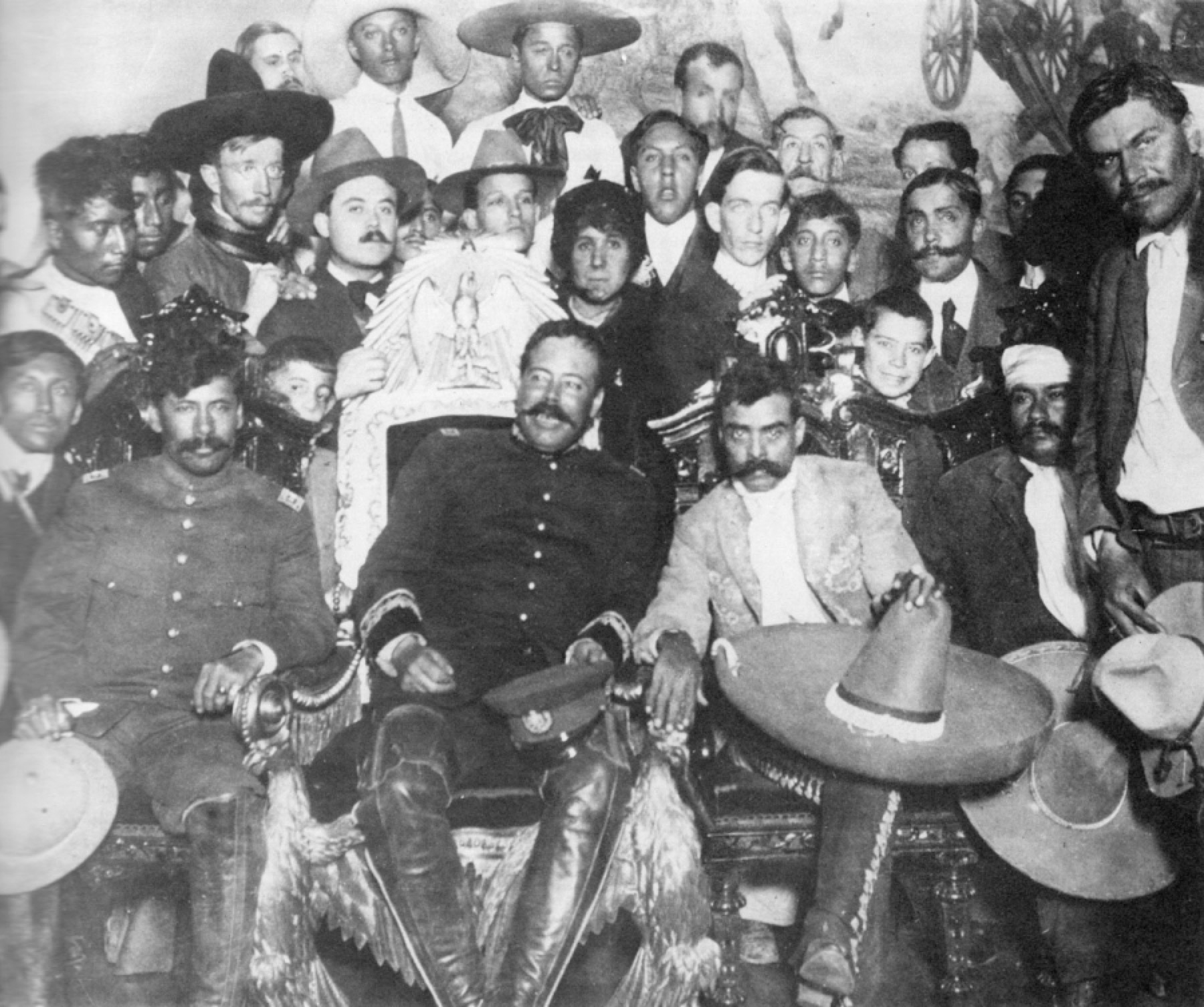

Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata in Mexico City. December 1914

EMILIANO ZAPATA COMES TO SAN ANTONIO

By Bárbara Renaud González

The Alma in the Alamo: Stories from San Antonio’s 300th year

Emiliano Zapata, peasant and spiritual leader of the Mexican Revolution, wasn’t killed during the Mexican Revolution. In his sombrero, moustache, and muslin garb, he still lives in the descendants who crossed the border with their family’s property titles sewn into their clothes, settled in San Antonio, and are categorized as undocumented or illegal. Like two elderly siblings, Lupe and Luis, whose story is about a crossing that never ended.

The Mexican Revolution that made Zapata so famous was a war that killed ten percent of Mexico’s population—the children of the big haciendas and their campesino workers alike. It lasted ten years and people starved—like in today’s Syria. The survivors of the Revolution arrived in San Antonio in the twenties and thirties. They had no choice. My own mother, who was born during the Mexican Revolution, told me once that after all that happened to her family, she didn’t believe in owning land anymore, that it belonged to everyone. She used to say that if we could become a world of at least two cultures, American and Mexican—this world would be perfect. My mother saw the border as a metaphor for possibility. To her, the border wasn’t geography, but poetry. Sometimes the border is a crisscrossing, with some children born here and others born there. Not a river, but a poem filled with words waiting to be written down. A brave new music.

Like my neighbor, Lupe, who was born in San Antonio. As the oldest of many, Lupe was born here because her mother came to visit relatives in the early thirties. Like my own maternal grandfather, Mexicans have travelled from there to here to work on the railroads, to work in agriculture, to visit relatives, and because they want to see another world, too. Lupe’s mother returned to Anenecuilco, Morelos, in Mexico, with Lupe in her arms. El destino. For some of us, it is our destiny to cross borders over and over again. As a young widow in Mexico, Lupe returned to San Antonio to pursue a career after World War II, when America needed workers. She quickly got snapped up by KCOR, the historic and independent Spanish-language radio station in this country, because of her old-world Spanish.

Lupe interviewed all kinds of people on air. Throughout the years, she helped half of her siblings come to the U.S., where they settled and became middle-class professionals. The other half stayed in Mexico and made their lives as engineers and businessmen, too.

Lupe was separated from her youngest brother, Luis, who was born in Mexico. She had raised him after her mother died and missed him terribly. She convinced him as a young man in the 1950s to work on this side of the border, and he married and had children here. In time, Luis became an esteemed master carpenter. Now blind and divorced, he depends on Lupe. And his English is better than hers because he worked in Chicago and Georgia for long periods of time. He was also recruited to work in Europe, turning down that opportunity to stay with his family, and of course, Lupe.

Last summer, I saw the iconic painting of Zapata and Pancho Villa’s arrival in Mexico City while visiting Lupe and Luis at their home in San Antonio and heard the story of their revolutionary uncle. Then the rest fell into place: their love of democracy, their constant reading, their informed politics, their infinite generosity.

Their uncle was Emiliano Zapata’s right-hand man, standing next to him in a photograph taken when the two victoriously arrived in Mexico City in December of 1914. Everyone I know has seen this photograph; it’s in Mexican restaurants all over Texas. For Latinas like me, this is better than claiming your heritage from the Mayflower. This is like seeing your ancestor standing beside George Washington as he crosses the Delaware.

In the case of Mexico, the Revolution was a political one. The Mexican elite, descendants of the Spanish elite, were overtaken by the new mestizaje—the mixed people of Mexico. The war was over land, as most of it had been awarded to the Spanish and the Catholic Church. But nothing really changed. The poor got poorer, and the rich kept their power. Emiliano Zapata was an indigenous blood-native of Mexico, and he had his original papers. He died trying to make Mexico honor them.

We are all children of Zapata. We resisted, we fought, we died, we crossed the border to survive. We have fought more wars, won some, lost others. And we still don’t have any land.

Our land right now is my memory. My books. My story.

Lupe and Luis’s family never really regained their ancestral land. Just like Zapata, who was the inheritor of land appropriated by the owner of the hacienda where he worked as a horseman. He and his family lived in a starving, chewed-up, poverty. This is the basis of the Mexican Revolution: Tierra y Libertad, or Land and Liberty. But the heart-pumping memory of land and its sharing remains in both Lupe and Luis. I saw it in the way Lupe would bring me a plate of enchiladas or the way she raised money with those enchiladas to contribute to a family’s emergency in Mexico. She was always doing something like that. I remember how she and Luis asked me to help them register to vote in our last election. And I did, though neither could see where to sign. They asked me the best questions about American democracy. They talked about how worried they were about the rising attacks on Mexican immigrants, the war in the Middle East, you name it.

Their questions were better than MSNBC. Their analysis was too richly Michenerian for the New York Times. They were walking libraries. They had read all the great novels, too. They were a novel.

Lupe died last week from liver cancer at eighty-six. Something unusual because she didn’t drink. The only addiction she had at the end of her life was playing braille-dominoes with her brother. And voting. She was constantly worried that the wealthy and privileged here would ripen the conditions for an American version of the Mexican Revolution.

As Lupe’s health failed last summer, Luis’s American daughters separated the siblings, sending the seventy-plus-year-old brother to a rehab center. Lupe was going blind too, she was tired, telling everyone she had digestive problems—not the truth. Losing her brother meant that she couldn’t live alone anymore, and was forced to pack up and leave for Mexico, where her granddaughter, an engineer, assumed care of her.

Luis stayed in San Antonio, visited by his daughters who haven’t told him that his oldest sister died. He can’t take it, they say. He is so frail.

Lupe and Luis travelled back and forth between two countries constantly until they couldn’t anymore. At home in each, trying to make the best of both. They witnessed many people re-establishing old borders as new, and shrinking their lives to fit inside them. The two siblings kept their passports close for a country that has no name but in their hearts. Both knew that the border of ideas is a place where you can be burned, decapitated, assassinated, arrested, hung, and then celebrated as a nation’s hero.

Only to resurface as a monster when fear crosses the border again.

“The Alma in the Alamo: Stories from San Antonio’s 300th year” is a part of our weekly story series, The By and By.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.