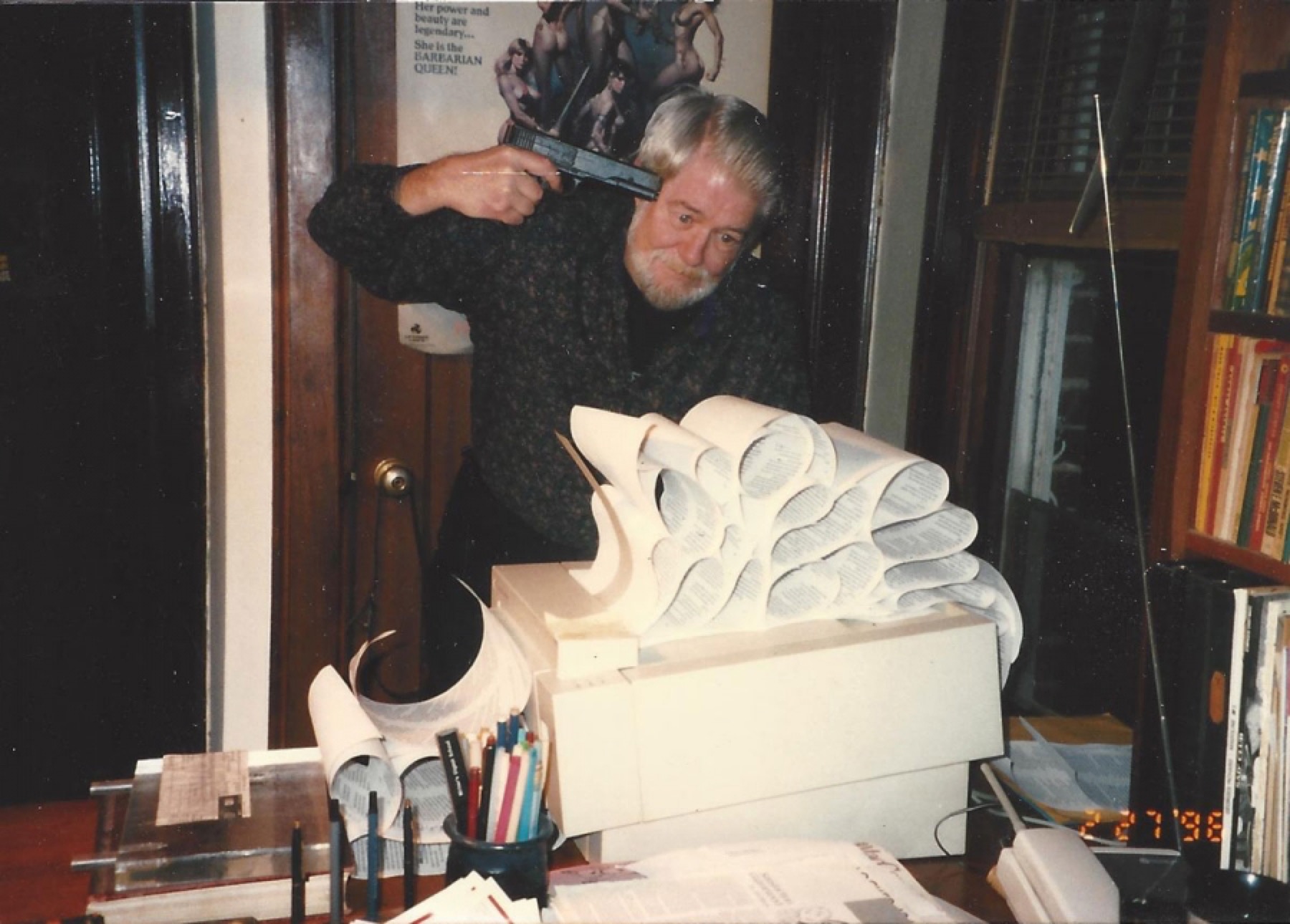

Andrew Offutt with his new printer in 1996. Courtesy of Chris Offutt

EXAMINATION AND COMPASSION

By Phil McCausland

Two years ago, I interned for the Oxford American between semesters at the University of Mississippi, where I studied English. During that summer, I recall a fact-checker working on a piece for the magazine that involved certain details of a possum’s anatomy. One assignment was to confirm the existence of a bone in the animal’s penis. Despite consulting marsupial experts and biologists, the checker could not get a straight answer. No one seemed to know whether or not possums possessed such a bone. Throughout the ordeal, the author of the piece, Chris Offutt, wasn’t easily reachable, adding to the frustration. (Eventually it was determined that possums do not; see Offutt’s essay “Baked Possum” for more.)

Offutt’s absence at that time is explained in his new memoir; his father, prolific science fiction novelist Andrew J. Offutt, had died. Chris, as the eldest child, had returned to his hometown in East Kentucky to box up his parent’s possessions and move his mother to Mississippi with him. The death of a parent is complicated, and having a difficult history with one can complicate their passing even more. Offutt explores the latter experience in My Father, the Pornographer, out next week from Simon & Schuster. The memoir elucidates the emotions that stemmed from the loss, the intricacies of their complex father-son relationship, and the author’s feelings about the four hundred pornographic novels his father published over a thirty-year writing career. It’s a genius combination of sadness and humor, brutality and joy.

When I returned to Oxford, Mississippi, after that summer I became Chris’s student and, later, his friend. One afternoon I ran into him at a bar and he asked me what I knew of pegging and another sex act in which a woman dons high heels and steps on a man’s testicles. I admitted I knew very little about either and listened to his waggish explanations. We soon moved on from the topic, and I considered it nothing more than a casual, if strange, digression. But for more than two years, subject matter like this consumed Chris’s life as he worked through 1,800 pounds of his father’s archive, including countless manuscripts, tens of thousands of pages of letters, and various comics, porn, papers, and paraphernalia.

Andrew Offutt quit a job as a successful salesman at thirty-six to become a writer of science fiction and pornography and had an incredible output under a number of pseudonyms. Through the success of titles such as Bondage Babes, Swallow the Leader, and Pussy Island, Andrew supported his family—an act that Chris, an acclaimed writer himself, ultimately deems courageous.

Last month, I returned to Oxford to visit Chris Offutt at his home, a barn in the midst of renovation. Like the house he grew up in in Kentucky, it is outside of town, in the country. We sat in his office, next to his father’s old writing desk and four liquor boxes of his father’s pornography—all of the archive that remains in the house, now that the book is done. Before I could ask my first question, Chris cut in, and we went from there.

I know this interview could be cool in one way, but it’s probably not completely comfortable for you.

Yeah, this is a pretty personal book.

Is it? Well there’s nothing I won’t talk about.

I’m curious about the work of digging through your father’s physical archive—what did the average day of research consist of?

There were over a hundred boxes, and they were stacked up in my living room. When I started going through them, I didn’t have enough space. I took every table in the house and made a giant horseshoe shape and put six chairs—two on each side—and then would begin sorting through them and taking notes and come in here and write.

Going through the boxes: first they all smelled of the house I grew up in, just the dust and cigarette smoke—all of it. The pages were yellow and old. There were a lot of memories that got triggered by going through it.

I’d work ten to twelve hours a day on it. I didn’t leave the house for a summer. People thought I was on vacation, that I had left the county. I didn’t go anywhere for the holidays. Melissa [Ginsburg, poet, author, and Chris’s wife] went to see her family three or four times, and I would just be here doing it. It was obsessive, but I couldn’t see stopping and didn’t know how to do it faster. I wanted to get to the bottom of it.

Did it start as a book project or as a deep fascination?

Neither. In Kentucky, I’d boxed it all up and I decided to go through it all later. I didn’t want to throw anything out. My siblings wanted to get rid of everything—I thought, No, Dad deserved a bibliography as a writer. He’d never assembled one. So that was what it started out as.

There were the published books, but then there kept being books that I wasn’t sure if he’d written or not. The only way was to confirm that was to go through and find a manuscript; that was a lot of what I did. Sometimes the titles changed, sometimes the characters changed—so I really had to do a deep comparison of the book and its potential manuscript. Because in addition to the porn he’d written, there was his collection of porn, which was another four hundred novels. I knew his style of writing and the kinds of themes he pursued, so I could rule out some stuff. I also knew the times when he was active, so there was a window. I realized there were forty unpublished manuscripts; he had more unpublished manuscripts than most writers publish in their lifetime.

Some of them were mysteries, and I called porn book dealers—mainly on the West Coast and one in New York—to get information. There was a hesitancy to talk, because it still has a taboo, but once I told them what I was doing and who my dad was, people were really eager. There are two books that remain unaccounted for that are referenced to in Dad’s work. I called Dad’s editor and publisher—he’s in his late eighties now and lives in Arizona. His name is Earl Kemp, and he was the last guy in America who went to prison on obscenity charges, in the seventies.

He said, “Oh yes, I remember your father. Yes, I remember those books, but I don’t know what happened to them, I don’t remember the titles, and I don’t know when or if we published them or what name we published them under.” It was such a fluid operation, and Dad had said he’d done these books as a favor to Earl after he got out of prison. Well, that was what he always said to the public. They were published under a female pseudonym, the only female pseudonym he ever used. He called them “lightweight incest” books, which is a funny term. That implies there’s a heavyweight. Where is the line between light and heavy incest?

There were also tens of thousands of pages of letters and his early works that go all the way back to college. There was nothing from high school, although he claimed he wrote two novels in high school. The earliest extant work was a short story—that I thought was a pretty good short story—he wrote when he was in college.

How long was that process of going through the boxes? Were you still going through them as you were writing?

At the beginning it was just to establish a bibliography, but I began taking notes about the work in order to keep it all straight in my head—I had to, there was just too much. And it was overwhelming in a number of ways: emotionally and psychologically. The notes began to become more extensive, and I realized maybe I should focus on these notes, too. So I began writing a little more seriously about what I was uncovering, what I was finding out, and what my thoughts and feelings were as I went. In a way, writing about it as I did it was a method to make the process more acceptable to me—it gave me an outlet to write, while at the same time making it palatable, the material I was dealing with.

I finally had all these pages, and I didn’t really know what I had. They weren’t sequential, there were many short sections with scrawled headings that did not always match what the material was—four pages here, eight pages there, ten—I had to cobble it all together, figure out what I had, what worked and what didn’t. As a result, there’s a hundred-fifty pages, almost two hundred pages that I cut out of the final book. They just didn’t seem to fit. I cut out a lot of stuff about the porn industry, the porn publishing world, about the history of it—stuff that I found really interesting but didn’t really apply.

In the book, you mention that in the nineties you considered writing about your father and your childhood, but you didn’t because your mom asked you not to. When you started this project was there any hesitancy?

No, not really. I had tried to write about my childhood a couple of times before with big plans. I had journals and diaries and everything I wrote as a child, all the short stories. I started writing at seven and I saved it all. But every time I started writing about that it became about my father, and I got depressed.

Both my mother and father did not want me to write about this, which was a problem in our relationship because it made me mad. My parents collaborated on porn without consulting their children, so to speak. Here I was, a professional writer being told by my parents not to write about that part of their lives. It really made me mad, and I did it anyways or I started to.

What I wrote at that time didn’t work because the motivation was anger. I was so irritated by the whole situation, I think there was anger in the work that I did. But then I was also still trying to protect them. With Dad, I think I was simultaneously trying to hurt him by imagining him reading it but also protect him. Both are suspect motivations and the combination is terrible. So I stopped.

When Dad died, those obstacles weren’t there anymore. There was no motivation to hurt him. And he was dead, which meant he couldn’t hurt me anymore. His death gave me compassion for him that I’d never had before. As I began going through his archive, it became much more interesting than I thought. I really had no idea the extent of his involvement in pornography. He passed as a science fiction writer to the world, but also to his family.

It really seemed like you avoided that bias, that anger, and there’s an immense amount of control as you describe those early years. How did you balance that, and not tend toward crucifying him?

There’s a long history of bad memoirs written by angry offspring. Sons and daughters are mad at their parents. They’re not that interesting to read. They might be valuable for the writer to write, but I didn’t want to write something like that. I knew this material I had had the potential to be very strong, very powerful. I thought anybody could take this material of dad’s career in the hills of eastern Kentucky, in the woods, contrast it with my childhood in that same place, an unusual place—anybody could take that material and make a mediocre book. I didn’t want to do that.

I thought: I need to overcome that, I need to transcend the material, and whatever I write needs to avoid the salacious, scandalous aspects. Part of that turned out to be trying to understand my father from his work in a way that he would never have allowed while he was alive—ever. It was impossible to communicate with him very well. Then it was just: Well, I’m a grown man now, I’ve got grown children, and I have this writer’s archive that I’m interested in.

The other thing that happened as I was going through this process and going through the work and trying to write was that I had to be objective, really objective. And not judgmental. That left examination and compassion. I think that this objectivity created distance in myself from everything—a distance from my own existence—which was essential in order to confront this material every day, the constant barrage of pornographic depictions.

In the book, your brother says to you, “You’ll always be afraid of him.” I wondered if as you were going through it, if that fear or anxiety resurfaced. You’re saying that it didn’t at all?

The fear didn’t. If it did, I wasn’t aware of it. The fear didn’t. He was gone. Whatever anxiety it may have triggered—and I was sad during part of it, the whole process was sad—I think it was tied up with the death of a father, even if it’s an odd man you don’t get along with. He’s still my father. Dad died. I’ve got his desk, his gun, and his porn. No matter what, it’s that.

But whatever anxiety I had probably just fueled my energy because I was exhausting myself in a way that I don’t think I’d ever done before. I’d experienced anxiety, and that would usually keep me up but I slept well during that period. I didn’t have the typical problems associated with anxiety: attention, focus, fatigue, or insomnia.

The more I learned, the more I ultimately realized what became impressive. His prolificacy for one thing—the rapidity, the speed, the discipline—but also what he was able to accomplish despite what were pretty severe limitations that he had on an interpersonal basis. That became really interesting to me.

He had considered a career in politics. He was a successful salesman. This writing life of his he started at thirty-six-years-old. I hadn’t really considered that before. Seeing his material and seeing his writing up until then and realizing the references to me as a child in some of the work and realizing that this is a man at thirty-six-years-old who had four kids, a wife, and a mortgage and a successful business career just quit everything to write—that’s unusual.

You discuss your dad’s early work and how, as a writing professor, you’d consider him a student with immense promise. You write that you’d say to him, “Don’t squander your talents.” Do you think he did?

His earliest work in my opinion is his best. I don’t mean the college work, but his work from around 1968 to 1972, when he was in his early thirties. Then he had to write faster and faster, which he did; this meant revising less, relying less on research—he loved research and his early books were heavily researched, whether it was science fiction or pornography or fantasy or a historical medieval novels—and more on invention. He also became more socially isolated and drank more. I think the combination of all those things affected the quality of his work.

I don’t think Dad cared. The quality of work was not as important to him as getting it out there and getting a contract and getting more, being known and having another pseudonym. He delighted in having pseudonyms and getting one over on the publishers. It was a very private delight; he couldn’t share it with that many people.

Do you think he ever wanted literary recognition? Did he want a career like yours?

He studied English in college and started writing seriously in college, even though he’d written as a child, same as I did. I think with Dad, he loved science fiction and other-world adventure novels. They were all popular in the thirties and forties when he was young and reading them. He believed he could write better than the writers he’d read and learned from, and that would be what he would do and he would be a great writer of science fiction and the other subgenre—planetary adventure novels is what I believe it is.

But that market dried up right around the same time that he decided to quit everything and focus on writing. Also the American economy really fell apart that same year—1971 and 1972—so there was this combination of things. He had changed his life drastically to write and at the same time there’s this huge market and demand for pornography because the world was changing: obscenity laws were relaxing, it became less taboo, you had X-rated movies in theaters, and porn bookstores were in big cities whereas before they had to be tucked away. He was at the right age and right time to take advantage of it. I think he exploited the demand for it and in some ways was exploited himself.

Andrew Offutt reading in 1974. Courtesy of Chris Offutt

Andrew Offutt reading in 1974. Courtesy of Chris Offutt

I’m curious about your use of humor. How do you earn that or how are you able to place that into a work like this, that is both sad and upsetting?

I have no idea. I don’t even know what would be considered funny in there. I know that often I can write deliberately to be funny. I am capable of it and will set out to do it. Only recently have I set out to write in a comic, humorous fashion—mainly with the Oxford American food essays. Before, humor was in my work, but it would just creep in there now and again. It was in language or in scene, more like black comedy. With this book, I have no idea if anything in there is funny. I’m surprised to hear you say that because I can’t remember anything in it that was supposed to be funny or considered comic. I’m glad there’s humor in there.

The book covers an entire career but isn’t structured chronologically—yet the narrative travels through time so easily. Somehow, I never felt in danger of getting lost. How did you figure out the structure?

At a certain point, after almost two full years of dealing with this, I had gone through all the material, or the majority of it—I didn’t read everything—and felt completely familiar with it. I had read as much porn as I could stomach, looked at as much visual porn as I would ever want to look at again, and had three hundred pages of a manuscript. I realized, yes, there are more things I can write about, there are more avenues I could explore, there are things I would really like to examine in greater depth, but I was done. I was exhausted from it. I needed to stop.

I took all the material that I had and printed it out, and realized, Oh my god, this is a gigantic mess. The first thought was that revising these three hundred pages was as oppressively overwhelming initially as the opening of all of the boxes. The biggest creative effort was really how to structure this material in a way that made sense, was not confusing, and that moved through time. The book, I realized, covers from about—the earliest reference is in 1945, when dad was nine or ten, all the way to present day. He died in 2013.

Your mother is a really interesting character; while your father is alive she’s this incredibly passive figure, but as you move into the present we see this transformation.

She’s eighty-one. She’s a kickass old lady who is charming to everybody.

I don’t think I was aware of those changes that she was undergoing, so it’s good to hear that is in there. Every time I would see Mom, I would try to record our interaction as honestly as possible. I knew she had to be part of this narrative about Dad. She was part of Dad’s life and a partner in much of his work. She was the ultimate, final source.

It was a jolt for her. Not only did her husband die, but she left her house where she lived for fifty years and moved to a town in Mississippi. She lived her entire life in two counties in Kentucky. It was a big, big transition. Now she travels all over the place.

One of the things she said after reading it was that it made her miss Dad. I was astonished by that response because my thought was “My gosh, I’m afraid that I’ve written about her husband in a way that she was either blind to or didn’t want to know about or want to know about the effects that it had on me and my siblings and that might hurt her feelings.” It took me a few days to realize that if the book about Dad made her miss him, then it was an accurate portrayal. It was really powerful. And then we’ve never talked about it since. Now it’s UK basketball or whatever she bought at Walmart.

Do you think you learned too much about your father?

I think I was in an unusual position. Most people never have the opportunity I had to learn about a parent. They just don’t. But Dad never threw anything away. He saved everything—everything! He was born in the Depression, he didn’t throw anything away, and they lived out in the country where they didn’t have regular garbage pickup; Mom didn’t want to throw stuff away because she thought it would inconvenience the garbage men. I always thought, Wow, that’s an unusual way to think about garbage pickup.

It wasn’t a case of learning too much, it was more a case of realizing that I can’t shy away from anything. If I’m strong enough, if I have sufficient courage, then I can maybe make something out of this.

My Father, the Pornographer by Chris Offutt is out on Feb. 9.