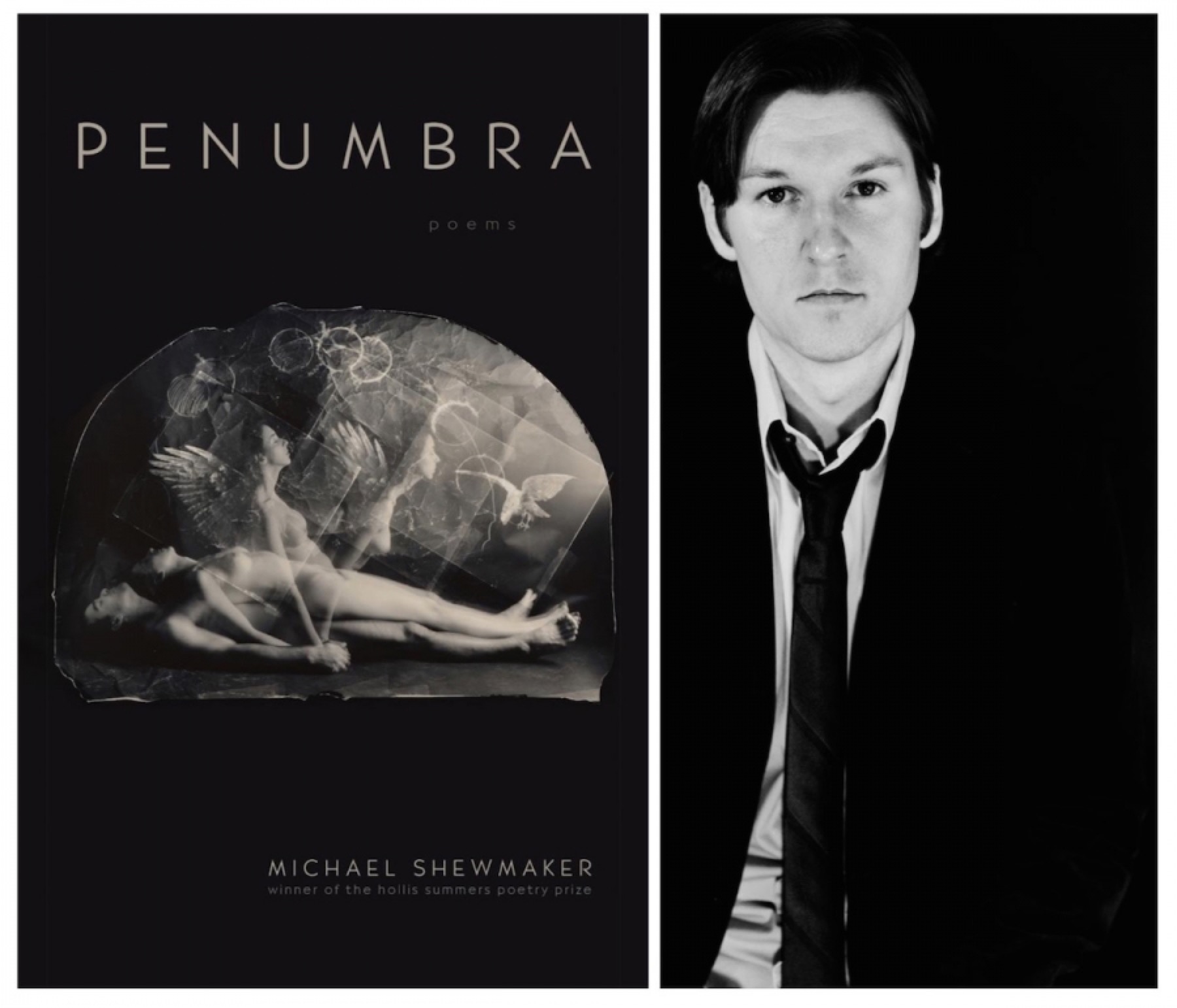

Michael Shewmaker’s debut collection, Penumbra, is just out from Ohio University Press.

FAITH FROM THE SHORES OF DOUBT

By Chad Abushanab

Penumbra, by Michael Shewmaker. Ohio University Press, 2017.

Michael Shewmaker’s debut collection, Penumbra, is the recipient of Ohio University Press’s Hollis Summers Prize, an open competition for a best manuscript from a poet of any rank. Hollis Summers, now too commonly forgotten, was a Southern poet given over to the pleasurable demands of formalism, believing that minding the rules of form required more from its writer’s soul, despite the trend of his time to compose more freely. In this way Shewmaker’s debut is perfectly paired with Summers’s legacy, as Penumbra is most certainly an introduction to an exciting new Southern poet of both dynamic skill and daring spiritual quest.

Penumbra, aptly named for the space of almost-illumination in an eclipse, contains virtuosic performances of formal technique, with poems ranging from traditionally received forms—Shewmaker is particularly adept at sonnets—to tightly wound nonce shapes, of which “Digging My Father’s Grave” is a superb example. I could spend the entire review discussing the poet’s lively attention to matters of prosody, but what I find even more impressive is the true sense of cohesion among the book’s poems. These pieces belong together, and their main concerns intertwine and converse over the arc of the book, dredging up answers in the form of more questions. We hear utterances across great divides: faith from the shores of doubt; death from the land of the living; darkness from the light, and vice-versa. Perhaps most importantly, Shewmaker increasingly asks the reader to share the poet’s occupancy in these uncomfortable, liminal spaces, to eavesdrop from the beyond.

The act of listening, then, becomes an important thread. We observe listeners in the act of listening, as in the cryptic and beautiful “The Lover.” In “The Pastor,” which was published in the Fall 2016 issue of this magazine, and “The Pastor’s Wife,” two speakers create a single story by sending their fear out into the ether. Or, as is the case with the macabre dramatic monologue “The Baptist,” the reader is approached by a voice actively looking for reception and a sense of understanding—“Don’t worry, son. I’m no evangelist./ Just try to think of this as my confession,” the speaker says in the poem’s opening stanza. We may be horrified by what we’re told (“The Baptist” spins the narrative of a serial murderer), but Shewmaker requires us to listen, to care, wringing humanity and empathy out of the reader as well as the speaker.

And yet among Shewmaker’s cultivation of multiple voices, there still emerges a strong sense of singular narrative consciousness between the poems of Penumbra. Pieces such as “Digging My Father’s Grave,” “Horoscope for My Dying Father,” and “Photo Found on a Dead Man’s Phone” generate the sense of a single, specific tragedy being replayed again and again. It suggests a likeness between that story—the death of one’s father—and the other tragedies and mysteries explored in the book. The inclusion of this meta-poem narrative forces us to reconsider seemingly unrelated poems in light of that subject, adding an extra layer of meaning to works like “The Baptist,” where a different kind of father/son relationship is realized. Or, as in the book’s powerful closing poem “The End of the Sermon,” how the speaker—a preacher in a crisis of faith—“spoke a single word” to the sky, only to receive “no answer.” These moments—powerful in their own right—are transformed in the shadow of the recurring dying father, making for multiple interpretations and guaranteeing rewards on multiple reads.

Of course, other elements of language bind these poems together. In addition to Shewmaker’s formalism, the poet has a propensity for carefully controlled syntactical arrangements. Take the closing stanza of “The Artifact”:

As the sentence tumbles over line breaks, the central idea is affected by a series of qualifiers, making what might initially be a simple utterance increasingly complex. In its best usage, Shewmaker’s syntax has the ability to enact the poem’s drama over the frame of the line. We see this technique used again and again throughout Penumbra, constantly modulated to suit the individual speaker of a particular poem, but all originating from a poet who dares to reach into the unknown for some expected cadence, returning again and again with something not only fitting but illuminating.

And perhaps this is the best way to bring the book back to its focus on versification. In Penumbra, I can’t shake a sense of faith-finding in the enactment of the verse itself. Despite the Summersesque ease with which Shewmaker satisfies his meters and rhymes, here he separates from his prize’s namesake by insisting on a sense of risk—how will each particular line complete itself? This is especially apparent in his sonnets, where he manages to remain syntactically and rhetorically surprising while suiting the requirements of the form. After all, much of the book’s interest lies in the tight-rope act which is the cultivation of the soul. It’s fitting that we should feel, too, that tension between sound and sense as clearly as we feel it between faith and doubt.

Ultimately, it is this space—the space shared between two opposing states—that Penumbra explores so well. Shewmaker’s exceptional debut hinges on the need, not to resolve form, but to further open it, a puzzle, a question, as though the very act of questioning keeps him in balance. Perhaps the penumbra, in this sense, becomes that most human state of being—one of uncertainty, piqued by hope.

Read “The Pastor” by Michael Shewmaker, from our Fall 2016issue.

Enjoy this review? Subscribe to the Oxford American.