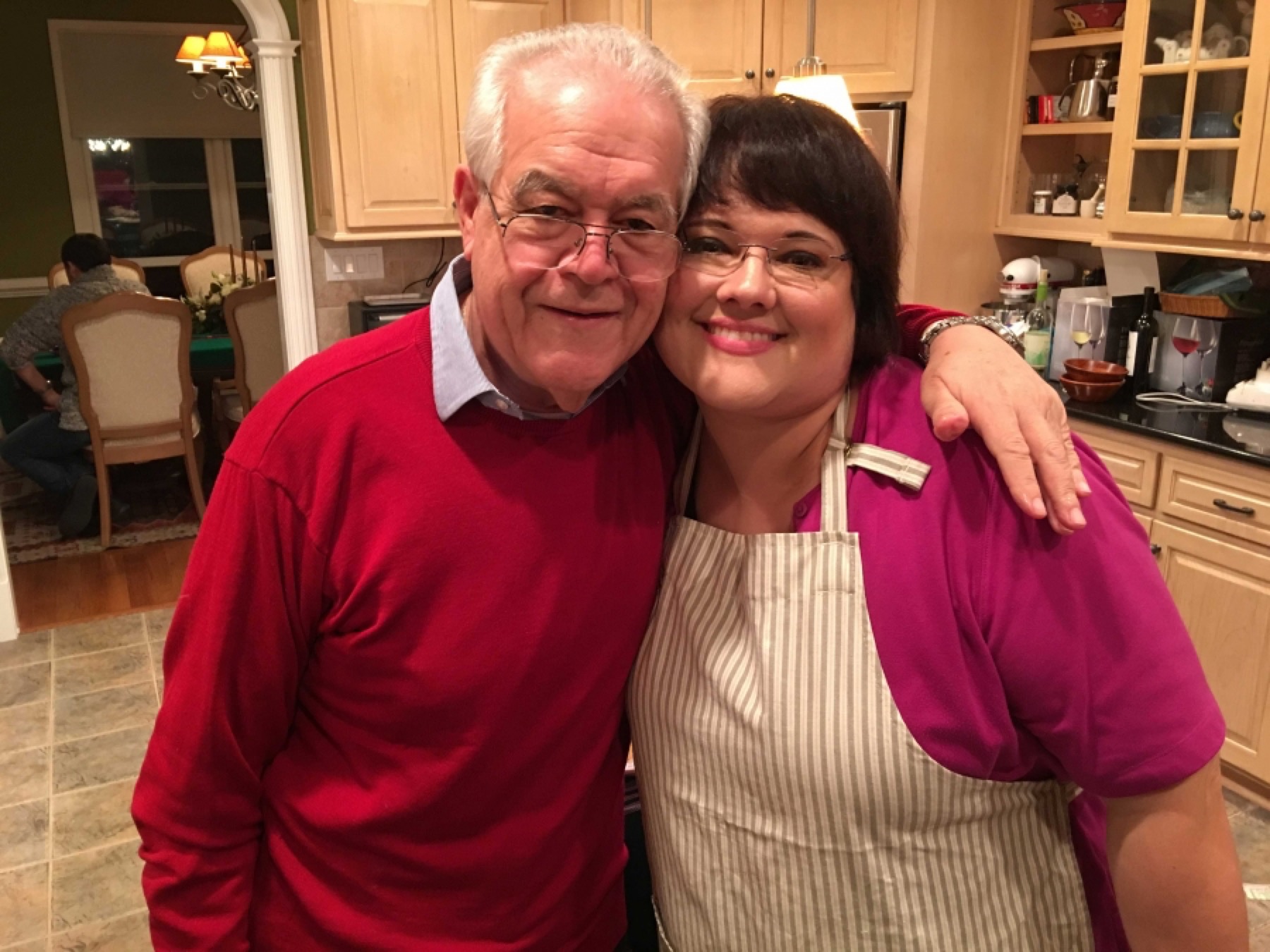

Sandra Gutierrez and her father | Photo courtesy of the author

FOOD MEMORIES

By Sandra Gutierrez

Chronicles from the Nuevo South

We all have an emotional connection to eating—anyone who has ever soothed hurt feelings or mended a broken heart with food will agree. Food can appease sadness, albeit only temporarily, and sometimes be a silent companion while we try to come to terms with loss. Food can also bring back a memory of a loved one and revive long-passed moments. I call these food memories.

I’ve never forgotten my first taste of bamboo shoots at a Chinese restaurant in Miami Beach with my Papa, or our many adventures discovering the taste of frog legs, snails, baby eels, or fish eggs. He taught me the joy of cutting into a slab of prime beef, still juicy and pink; to twirl sauced pasta on a spoon so that more would make it into the mouth; to add enough chile to bean dishes so that the palate danced without burning to numbness; and yes, to savor my first sip of beer. Some of those first tastes became the butt of many jokes, but others remained so deeply engrained in memory that they became a source of comfort and joy.

Miami Beach, 1970. The six-year-old girl held tightly to her father’s giant hand as they walked briskly through the sun-scorched streets. Her tiny legs had a hard time keeping up with his long strides. It had been a long day of shopping and sightseeing—they were exhausted and hungry. Her mother and brothers had preferred to hide from the heat in their air-conditioned hotel room. But the little girl and her father had bigger plans.This wasn’t the first time that they were going on a dinner date; nor would it be the last. They were food buddies—for life.

“Papa, where are we going?”

“I’m going to take you to eat something you’ve never tasted before. How would you like to try bamboo?”

“Grandmother has a fence made out of bamboo.”

“Yes, she does. Would you like to eat it?”

“Are we going to eat a fence?”

“Yes. I’m going to take you out to eat fence, cooked with chicken and vegetables in a delicious sauce.”

The restaurant was spartanly decorated, the walls a pale sky blue, with white and silver formica booths and red and gold paper lanterns hung from the ceiling. The father ordered from the menu in broken English, which the girl spoke rather well. She paid attention to every word he said—and at no time did she hear him mention any fence. Still, the girl imagined cutting into a miniature fence, piece by piece. She was delighted to get her own bowl of rice and two chopsticks, but she was eager to see the pièce de résistance. Soon, they were presented with two tall, stainless-steel tureens, covered with high lids. Her father lifted the lids, one by one, letting the aromas escape in whisps of steam.

“Ah . . . here you have them,” said the father. “Bamboo shoots!” He pointed to the thinly sliced, beige, and rectangular tiles nestled between diced chicken, carrots, celery, and onion.

He watched her closely as she carefully speared through one piece with a single chopstick and lifted it to her nose. She sniffed it—it didn’t smell like a tree. She studied it—it definitely didn’t resemble her grandmother’s fence of giant round stems, covered in thick, woodsy nodes. It wasn’t green like the grass attached to the bamboo she had seen in her tropical homeland, either.

“Are you sure this is fence?” she asked dubiously.

“I promise.”

Her father spooned some of the food onto their plates and pointed to all of the little pieces of fence. Then he took one, ate it with gusto, and asked her what kind of adventure it would be if she didn’t try a little bite? So her teeth bit into a slightly crunchy piece, and it burst with briny juice; it was coated in smooth white sauce that tasted of chicken soup. She took a bigger bite and swallowed—then she smiled. She had discovered that food could be an adventure.

I recently asked my friend Debbie Moose, who has authored myriad books, among them Buttermilk: A Savor the South Cookbook, if she could remember her first taste of buttermilk. She answered with a food memory.

“My earliest memory about buttermilk is about my father,” she said. “He grew up in the country in Iredell County, North Carolina. When my mother would make cornbread for dinner, he’d have the leftovers as a snack later in the evening. He’d crumble it into a glass, then pour in enough buttermilk—left from making the cornbread—to just cover it, stir, and let it sit for a few minutes until it became sort of pudding-like; then he ate it with a spoon. He did this every time we had cornbread.”

Teaching someone to cook can build comforting food memories that last a lifetime, memories that bring back feelings of deep love and shared intimacy while you learned to measure, stir, shape, season, and taste beloved recipes. Every time I bake almond cookies and roll them into powdered sugar, still warm from the oven, the spirit of my Tía María is near me. I can almost see her hands handling the fragile cookies so they won’t crumble. Perhaps it helps that I still make them with her old hand-carved wooden mold. When she taught me to bake almond cookies, she knew that she would leave me soon—she wanted me to remember her every time I baked them. Forty years later, I still do.

One of my dearest friends and my soul sister is Virginia Willis, who is a beloved, Southern author of five books, including the James Beard Award-winning Lighten Up, Y’all. Whenever we cross paths in each other’s hometowns, we make it a point to cook for one another. We keep it simple, often roasting a chicken or grilling steaks, and we always prepare a recipe that brings back memories of someone we love. For Virginia, this is often a batch of flaky biscuits, rolled and cut by hand.

“Sometimes I feel like I was born in my grandmother’s kitchen—it figures so prominently in my memories,” Virginia recently shared with me. “Undoubtedly, making buttermilk biscuits is one of my earliest and most favorite cooking memories. She’d roll out the dough and let me punch them out with her aluminum cutter, then let me make a handprint with the scraps of dough. It’s the same recipe I use today. Several years ago, I was teaching my godchild Ruby how to make biscuits. I reached to the board and took a nibble of the dough and said, This tastes like my childhood. She took a nibble and looked at me and said, Your childhood tastes good!”

Those of us who have found a vocation in foodways—not just a career—often have a strong emotional connection to food memories. I’ve spent my adult life trying to comfort others through food because I feel enormous joy while doing it. And it’s nourishing for the souls of others.

I’ve seen a grown man cry over a bowl of corn ice cream with praline sauce; it reminded him of eating caramel corn with his dad at a state fair. I’ve observed my students recall their grandmothers, mothers, fathers, or someone long gone when tasting a dish I prepared for a class.

There is cathartic power in food memories. They soothe and they strengthen.

Guatemala, 2017. The little girl is big now, but she still dreams of food adventures with her father—if only there was more time.

“Papa, please eat something.”

“I can’t taste anything.”

“Just a couple of bites, please.”

“I’ve no appetite. Remember our adventures when I’m gone.”

“Promise that you’ll find new ones so that when I see you again we can share more.”

“I promise.”

“Just not yet . . . just one more bite.”

The food memories will remain. There must be a corner table in heaven, a place where one can meet with those we’ll forever love. A place where food memories come to life once more.

I’m counting on it.

“Chronicles from the Nuevo South” is a part of our weekly story series, The By and By.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.