Big Class Books

FREE THE MEMORY

By Kiese Laymon

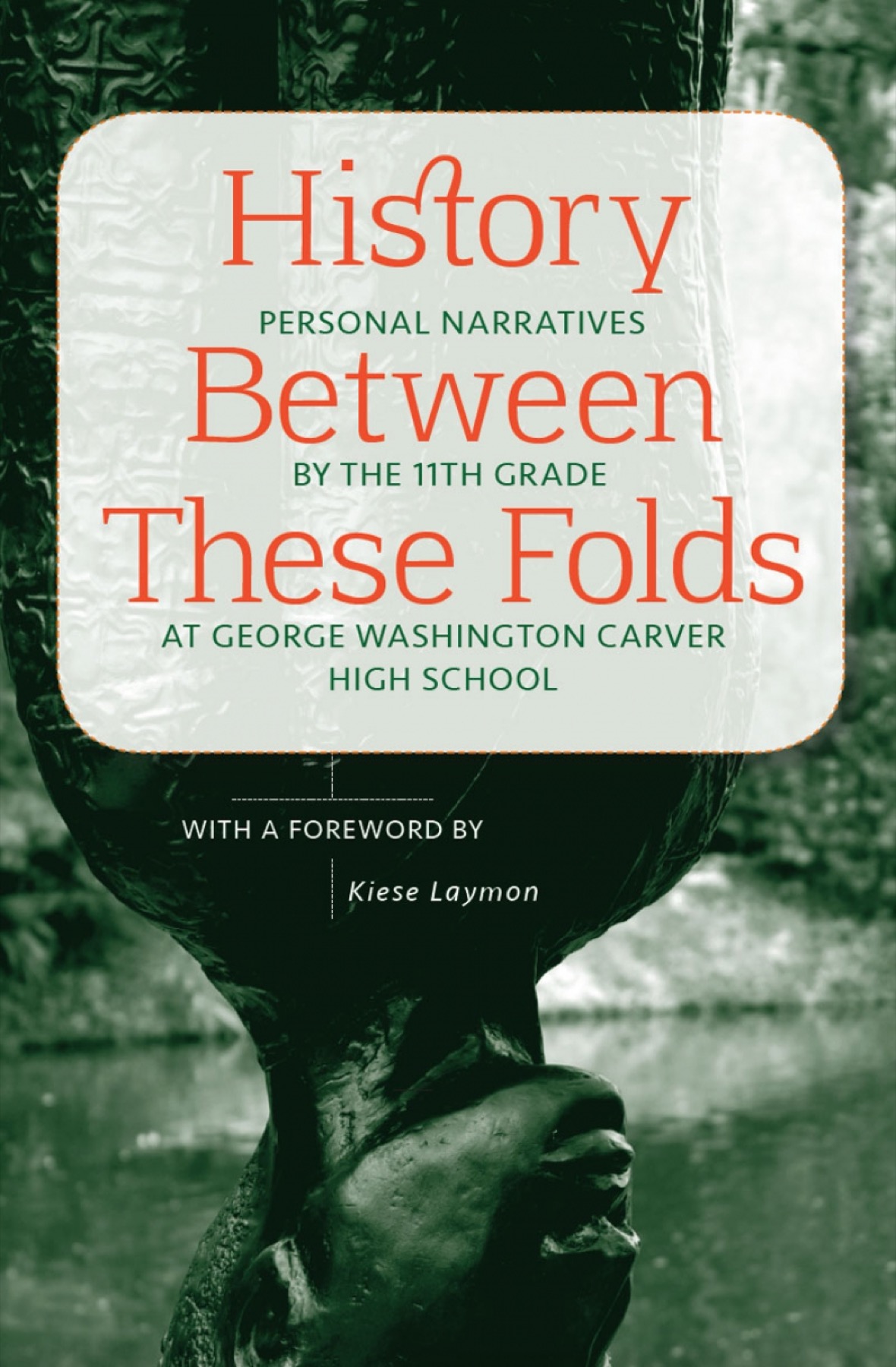

Foreword to History Between These Folds: Personal Narratives by the 11th Grade at George Washington Carver High School

During the spring 2017 semester, the junior class at George Washington Carver High School in New Orleans’s Ninth Ward worked with Oxford American contributing editor Kiese Laymon to write History Between These Folds, a collection of essays published in partnership with Big Class, a nonprofit organization focused on youth writing.

“Writing it was hard,” wrote the editors in the book’s introduction. “We had to open ourselves up and be vulnerable. We had to find just the right words to help people feel and understand the things we go through every day. We had to tie in our personal histories. And we couldn’t help but consider what people would think of us when they read our stories . . . Through this journey we learned we all have different voices, but we came together for one goal: to let people hear our stories and to tell the world about us. Yes, we are in New Orleans, but we are more than the stereotypes that come to mind when you think of The Big Easy. We are rare and powerful. Through this book we will make you laugh, we will make you cry, and we will challenge the ideas you may have had about us.”

Laymon wrote the foreword to the collection, reprinted below.

—The Editors

“When you don’t care about making other people feel pain, I’m wondering if are you are being a violent person? I wonder if America is filled with all violent people.”

I wrote these two sentences with a dull New Orleans Saints pencil in a black and white composition folder when I was fourteen years old. I was supposed to be taking notes in my Social Studies class in Jackson, Mississippi.

When I was fifteen, Mama and I moved from Jackson to College Park, Maryland, for a year. I spent most of my time in Maryland playing basketball, missing my friends, listening to Ice Cube when Mama went to sleep, and reading a book called Coming of Age in Mississippi by Anne Moody.

One Sunday night, I read over those two sentences I’d written in Mississippi. Nothing I’d read in school prepared me to think through my real relationship to violence in my home, my city, my state, or my nation. I remember looking at those two sentences, knowing there was more to say, but not sure if I should erase both of the sentences and start over, or if I should add something to what was already there.

Monday morning, before school, I kept reading and rearranging the words I’d written in Mississippi, trying to understand what the writing meant. After erasing and writing, I revised those two sentences and wrote:

When I don’t care about making other people with less than me feel pain, am I being violent? White people in Mississippi are violent to black people. White people in Maryland are violent to black people. Police are violent to my mother. All parents on earth are violent sometimes. Boys on earth are violent to girls. Mike Tyson lost tonight and no one on TV called him or the man who knocked him out, or the rich fans watching violent. The black man who knocked Tyson out was named Buster. Buster is a funny name for someone who knocked out Mike Tyson.

For the first time in my life, I realized that telling the truth was way different than finding the truth, and finding the truth had everything to do with revisiting and rearranging words. Revisiting and rearranging words didn’t only require vocabulary; it required will and courage. Revised word patterns were revised thought patterns. Revised thought patterns shaped memory. I knew that the memories were there. I just had to rearrange, add, subtract, until I found a way to free the memory. I understood in Maryland that sitting and sifting through memory took imagination and revision.

But even after embracing revision, I didn’t have anyone I felt comfortable sharing my revisions with. I’d never read the kind of paragraphs I was writing in school. My teachers in Maryland didn’t want to know my thoughts on violence or revision. My Mama wanted me to write about famous black political figures like Fannie Lou Hamer and Medgar Evers. My boys in Mississippi might have been interested in my revised paragraphs, but they were one-thousand miles away, and showing them my revised paragraphs felt like something they’d think only weirdos would do.

I’ve written and shared thousands of paragraphs since realizing I was a weirdo obsessed with paragraphs and revision, but I didn’t think about the first paragraph I revised twenty-six years ago in Maryland until I walked into George Washington Carver High School in New Orleans this February. The eleventh graders at Carver welcomed me into their space with plenty of questions. The students talked about their New Orleans, their families, their loves, their anxieties. They talked specifically about what they wanted to smell, taste, touch, feel, and hear five years into the future. They’d yet to write the essays in this book when I visited, but they were excited at the idea of being read by teenagers all across their city, their state, and their country.

Then they wrote. And they revised. And they wrote. And they revised.

When I asked the students on the editorial board at Carver whom they most wanted to read this book, they were clear. They said Jesus, Oprah, Solange, my dad, my boy cousins, Audre Lorde, America, Grandpa, people who struggle and people whose family turned their backs on them.

I’ve read the essays in this book at least ten times each, not because I have to, but because I don’t think there is another book like it in the world. The really terrifying thing is that I need this book even more now than I needed it as an eleventh grader. If every American book published in 2018 were written to the eleventh grade at Carver High School in New Orleans, the world would be less violent. If every American book published in 2018 were written by eleventh graders at Carver, the world would be more loving. Though these young folks are rarely written to in American literature, they know who they are. And they know who the folks are who refuse to see all of their complexity. “We are rare and powerful,” the younger writers tell us in the introduction.

I thank the eleventh graders at Carver for the brave collaborative work they have created. They are not just the best of this nation; they are what this nation can be if we all commit to a lot more revision and honesty. They are eleventh graders at Carver High School in New Orleans, and as you will soon see, taste, touch, smell, and hear, they are the History Between These Folds.

Please consider sharing our book with as many young people as you can.

Buy a copy of History Between These Folds.

Enjoy this essay? Subscribe to the Oxford American.