He Sang Me a Few Verses

The story of Gene Thomas and Bill Ede

By Sarah Graham

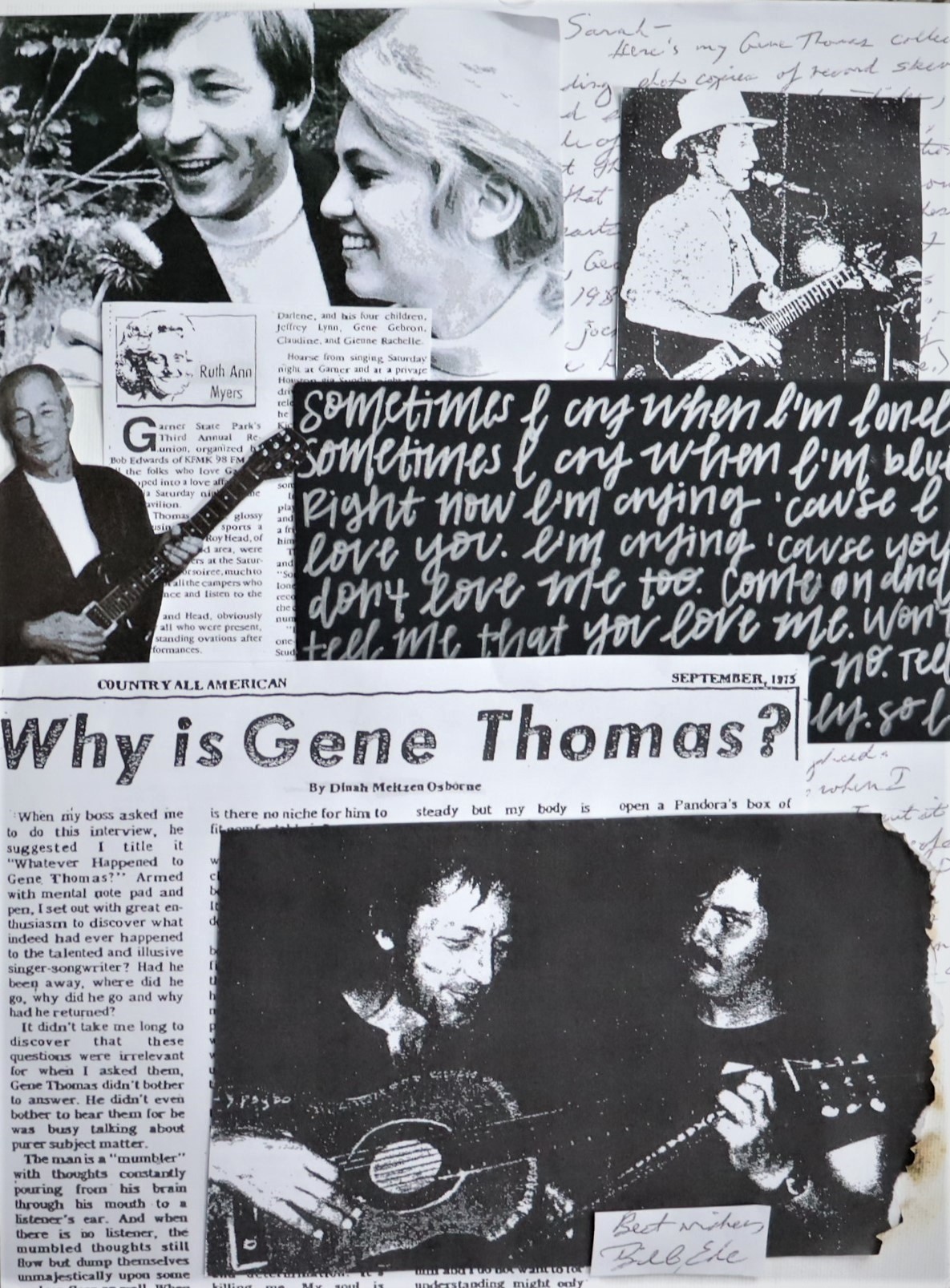

Collage of The Archive by the author

This exclusive feature is a part of the OA's Country Roots: Web Edition, an online extension of our annual music issue. Order the Country Roots Music Issue and companion CD here.

Bill Ede and I spoke on the phone for nearly an hour the first time he called.

Bill is a seventy-year-old singer, songwriter, and record collector from Louisville, Kentucky, who can only be reached on his fixed-line home phone. He writes music and writes about people who write music. He is an encyclopedia with two legs and a heartbeat. A conversationalist. An archivist. A friend.

Bill called the main office of the Oxford American and reached me, a receptionist by day and a burnt-out poet by night, fiending to write something other than nothing.

I was expecting another ghost caller. But instead I listened to a man rattle off stories of unknown Texas legends, the same ones he’d told a hundred times before. He has a fascination with lyricism, how melody and poetry burrow deep within our beings, how words can crawl under our skin, and fester within our soul. He has been known to meet up with the songwriters he most adores, writing them letters or sleeping in the hotel room across the hall, hoping they’ll write back, or bump into him at the ice machine in some sort of divine, deliberate serendipity. Bill told me jokes and sang me the choruses of old country tunes he thought I should have known, then thanked me for my time. He was expecting to make conversation with an answering machine.

Bill called to tell us the story of Gene Thomas, the man he calls his hero. Bill will mention Gene to anyone who is willing to listen, and he thought that the music enthusiasts running and reading the Oxford American might like to learn a little bit about the East Texas “swamp-pop” star with a soft voice and a loud mind. Gene was a self-taught singer/songwriter whose songs have been covered by Dean Martin, Waylon Jennings, Roy Orbison, Johnny Lee, Paul Revere & the Raiders, Don Gibson, Dottie West, the Everly Brothers, and Tina Turner, amongst others with big names in bright lights on busy street lines. In Bill’s recollection, Gene longed for the world to hear his songs and loved his music to the point of agony. He wrote about his severed ties with humanity, and wrote for those who found comfort in his cries. Gene was a devout father and husband. A prophet. A poet. A gentle voice in a world grown cold.

Though Gene garnered a small cult following, most of his fans are dead and gone. But Bill yearns to keep Gene’s legacy breathing. He wants the generations to know of his music, to sing his songs to their children, and their children, and so on. It’s been ten years since Gene left this earth, and most of us never knew of his existence.

Born Gene Thomasson in Palestine, Texas, in 1938, Gene didn't remember a life without music. He grew up listening to his father and father’s twin brother playing the fiddle, always in awe of their harmony, and the goosebumps crawling up his arms.

By age twelve, Gene was strumming on his grandfather’s guitar and started writing lyrics before he hit puberty.

“Paper dolls discarded long ago. Tender feet that chose the crooked road. Now they’re being bruised by the stones that we all throw… at the scarlet lady with no name,” Gene scribbled down somewhere at age thirteen. He dropped out of school the following year.

Gene was composing at sixteen and playing at clubs by his eighteenth birthday. His dreams led him to Houston, where he scoured the phone book in search of local record labels to no avail. He returned to Plainview and worked odd jobs to pay the bills and kill the time until his then-wife’s cousin heard him poking around on an organ a few years later. The cousin had ties with a local record studio and invited Gene to record a song. In 1961, Gene secured a record deal with his single “Sometimes” (often misprinted as “Sometime”), a song he had written only a night or two before. As Bill told me, “Sometimes” became a number-one hit in Houston, Dallas, San Antonio, and all other major cities in Texas, landing Gene a record deal with United Artists in Nashville. By 1962, his single was heard on radios all across the nation, and after hearing the song, Roy Orbison wanted to produce Gene’s further work, asking for him by name.

Despite the smell of fame, Gene was all on his own: no bandmates, or guitar. At each gig, he would play alongside whichever ensemble the venue had on hand. Gene always felt itchy on stage, and terrified when first recording his songs. He was a humble man, shy, and always mumbling. Local magazines predicted he’d be The Next Big Star.

When he got his first record deal, Gene was my age, twenty-two. Back then, my mom was in her mother’s womb; my dad still not even a thought in existence. My parents grew up listening to their parents giggling, then bickering—their fathers drinking cheap beer and playing guitar.

Mom would sing me the songs her dad sang to her. You are my sunshine, my only sunshine she’d hum, tucking loose strands of hair behind my ear. Dad blasted classic rock and impersonated Elvis Presley. He’d whistle the theme songs from our favorite childhood cartoons and nod along to whichever teen-bop-washed-up-Disney-star song my sister and I were listening to in the car. Mom was raised on white bread and Olivia Newton-John. Dad grew up with squirrel stew and the likings of Charley Pride. Mom’s dad, Grandpa Robert, was a clean-freak from Boston who collected cookbooks and fed stray cats up until he died. Papa Roger hand-built a beautiful A-frame cabin on the Caddo River and ate Spam off of the same knife he’d used to slaughter a small animal the week before. Both men were soft-spoken and big drinkers. Both gentle but thickened by war.

The only version of Grandpa Robert I remember is the one I’ve heard in stories. He would drink martinis and watch Grandma swing her hips to swing music then attend the opera and other shows that would now be considered drag. I never knew why my favorite childhood movie was The Aristocats until Mom later mentioned that he would watch it with me over and over. I tell Mom I remember him but I can’t.

After Papa Roger decided that his time on earth was through, the four of us went and stayed at his cabin on the river. I was seventeen. I remember Dad sitting on the porch, alone and drinking black coffee; Johnny Cash bellowing from the speakers on his phone. That’s all I remember Papa Roger ever listening to. When I miss him, I play “Folsom Prison Blues” and imagine him strumming along, holding his tea-cup poodle and puffing on a cigar.

I wish Mom would have kept the portable cassette player that she lugged around in the ’70s like it was a purse, or an extension of her body. I wish Dad would have kept the records he traded at school, and the eight-track he’d jam a popsicle stick into just to hear his own voice blare through the speakers. I wonder who sold Papa Roger’s guitar.

B

ill’s introduction to Gene’s music was in 1971, when he heard Lonnie Mack’s recording of “Lay It Down.” Bill couldn’t find the recording until several months later, when he got his hands on an Elektra-3 promo sampler LP, but the record didn’t specify who the man was behind the curtain. In 1972, he stumbled across a tapestry on the wall of a radio station that quoted the song’s lyrics, attributing them to Kenny Rogers, but Bill knew in his gut that the song wasn't Kenny’s. He then inspected a copy of Kenny Rogers and the First Edition’s album Transition, which credited “Lay It Down” to Gene Thomas. By then, Bill had already been performing the song around town for months without knowing the true artist by name.

Bill heard Gene’s voice for the first time later that year, while listening to the local country radio station. It was a new song, one he had never heard before. But something inside of him knew that these were Gene’s lyrics, even before the song ended and the DJ confirmed his suspicions. “That was ‘Watching It Go’ by Gene Thomas,” the DJ said. Bill could now put a voice to the mystical songwriter he admired, whose lyricism haunted him, seeming to leech onto a part of Bill’s brain.

In this song, Gene watches the outside world through the looking glass. In a sort of paradox, he questions his own free will and condemns his destiny. He writes of roaming the world on a puppeteer’s strings, alone and homesick for a place he’s never seen before. Where do you go when you’ve been? Gene sang, strumming along to the sanguine melody.

Bill only heard “Watching It Go” on the radio once more, but he had already started accumulating every record of Gene’s music he could find, collecting ten or so 45s throughout the following year.

In 1976, he snatched an album titled Hear and Now by Gene & Debbe. The LP was centered around the hit song “Playboy,” which reached number-seventeen on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1968, then went gold. Bill remembered the song hitting number-one in Louisville, as it was his little sister’s favorite record at the time. It took Bill a while to realize that this was the same Gene he knew of, as he wasn’t used to Gene singing alongside Debbe Neville, an aspiring crooner with a silky, seductive voice, who by then Gene had already married and divorced.

Gene changed genres like a chameleon changes colors, his songs a kaleidoscope, a cryptic camouflage. He was a one-man doo-wop group with a country twang and a pack of cigarettes; a horseless cowboy with a rum-butter voice and adrenaline pumping through his veins. Bill was utterly fascinated. He needed more.

Bill didn’t expect Gene to respond to his letter. Most people in the music industry never wrote back.

Gene’s third wife Darlene told Bill that if he wanted to meet Gene, he’d better get down here fast. So in September of 1980, Bill hitchhiked from Louisville to Longview, Texas, picking up a disposable camera at a gas station along the way. He stayed with Gene, Darlene, and their daughter Claudyne for three days in their home nestled near the Sabine River. Each man took turns serenading the other—Bill mainly played covers, but Gene sang originals, most of which had never left the four walls of his mobile home.

The two stayed up reminiscing about the good times and the bad times; the men they wanted to be but never were; the men they were but never wanted to be. Gene’s hands were always wrapped around an Old Milwaukee, and his guitar.

The night before he left, Bill was already drifting asleep when he heard Gene at the kitchen table singing endlessly into a tape recorder, as if he could never sing again, as if his songs would cease to exist come sunrise. Bill will always adore those tapes, all forty-or-so songs recorded for him alone.

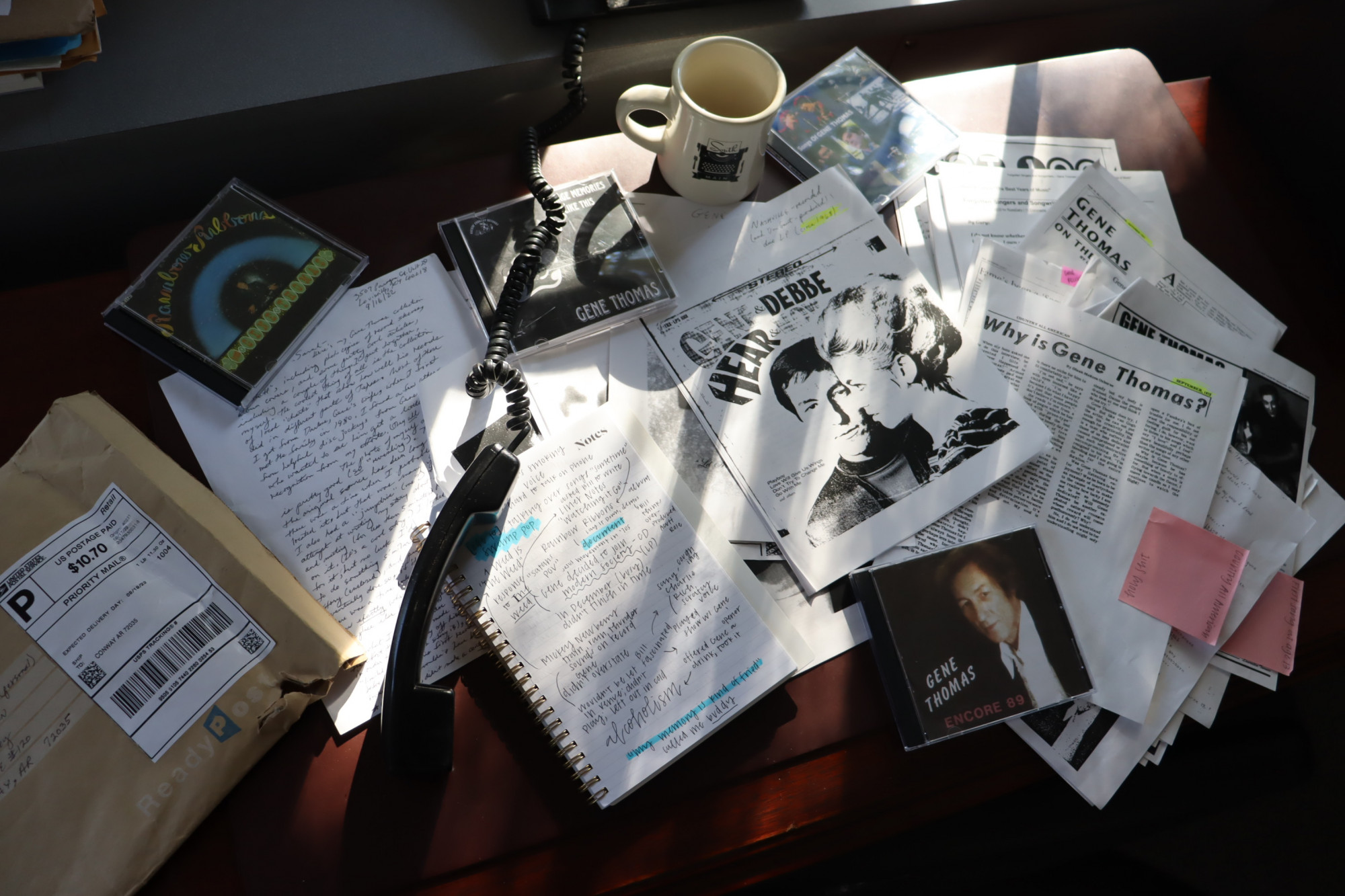

Photo of The Archive by the author

Bill told me Gene didn’t recognize himself in the photo he took of him on the disposable gas-station camera. Bones protruding and eyes glazed, it was the first time he realized how ill he had become.

He hadn’t stepped foot on stage or into a recording studio in over a decade. During his hiatus, Gene lived anywhere and everywhere, never staying in one place for too long. He kept writing, and drinking and writing and drinking, until he saw with his own eyes that he was dancing at death’s door.

Gene had weaned himself off alcohol by spring of 1982. It wasn’t long before he was back on stage, but putting on a show was never the same as it was decades before. It was uncomfortable to perform in front of a bunch of unfamiliar faces without a beer in his hand and booze in his blood. Sobriety felt strange, like wearing a pair of wet socks, or making conversation with an old, unwelcome friend.

Bill told me about one of his favorite humans on earth, a past editor of Louisville Music News. He talked of her keen eye and wit, the way she’d watch his shows and gush over his songs, until she couldn’t.

He once brought his guitar to the nursing home to play the songs she once loved, but she didn’t remember the sound of his voice, the shape of his face. The other patients tapped their feet and bobbled their heads to the tune, but she just watched, wondering who this strange man was, singing, and staring right at her.

Bill and Gene never lost touch. They stayed friends, phoning each other now and again. When the royalties ran dry and he fell back on hard times, Gene even tried selling his gold record to Bill to “keep it in the family.” Bill and Darlene still exchange Christmas cards from time to time.

Bill works the graveyard shift at the post office, the place where he’s worked for almost forty years. We both spend our waking hours packing up boxes and walking in circles, making a living off of sending mail to strangers before coming home to empty mailboxes and cluttered rooms.

We last spoke in September, when Bill told me he falls ill this time of year, and that this might be the last phone call for a while, until the wormwood and ragweed succumb to the first Kentucky frost. We talked for nearly an hour again. He sang me a few verses from Willie Nelson’s version of “Pancho and Lefty” then told me he’d better hang up before he started to cry.

The next day, Bill mailed me The Archive: a sprawling collection of articles, photocopies of record sleeves and album covers, pieces Bill had written about Gene, and a copy of the photograph the two took in 1980, the original long misplaced.

It seems like Bill owns every public record of Gene’s career, of his existence. He highlights all of the dates in the documents. He writes notes in the margins and amends the minor mistakes of articles now sixty or seventy years old. He sent me a two-page handwritten note, along with five burned CDs, two of which are from an album titled Teenage Memories Like This, featuring some of Gene’s greatest hits, as well as other songs that are seldom heard and hard to find. One CD is a compilation of Gene’s songs covered by other artists; another is an album titled Gene Thomas: Encore ‘89. He also sent me Rainbow Ribbons, which features songs titled “God Bless My Old Guitar,” “Jesus Hold Me,” and an alcohol-induced rendition of “Sometimes” in which Gene speaks over the track, as if he’s talking just to me. The CD was never released. I listen to the albums religiously, transcribing the lyrics into poems and tasting their sounds.

Bill has preserved the life of Gene deliberately and delicately, probably accumulating enough memorabilia to open a tiny library, or to curate an exhibit in some sort of niche museum.

Bill stockpiles articles and figurines the way that I mothball memories—storing them in my poetry, tucking them away in the folds of my notebook or brain. I try desperately to grasp onto the lives of late loved ones, listening to the music they loved and hoarding their things. Their stories are like heirlooms I wish to gift my unborn children; I must compile everything I know of their existences or I will begin to forget them, the way I no longer remember the shape of their faces, the way they said my name.

Before written language there was music, and poetry. The hums and thuds and echoes, a cry out to our fellow human beings. The sound the visceral lust for someone else out there to hear us, to listen. It is the knowing that our voices reach farther than arm’s length, that our words can linger, even for just a little while.

Gene’s music has bled through the generations. Some danced to his songs at their junior high homecoming dance, while others gathered in herds around the stage at Garner State Park, howling Gene’s name and handing over their worn records for him to sign. The lucky ones of the next generation grew up on Gene’s music, too. To them, listening feels like home.

Sitting in his overstuffed, faded blue recliner next to an ashtray and a portable radio, Gene clutches his guitar, and puts on his very last show. The collection is titled At Home With Gene Thomas and can be found within the depths of YouTube. The videos, recorded by a family friend with a cheap handheld camera, were uploaded nearly a decade ago and most only have a few hundred views. There are sparse comments on each video from straggling fans, reminiscing.

Gene died of lung cancer one year after the recordings and wrote songs up until the end.

Gene’s voice was bruised and beautiful; his words age like blue jeans. There is a warmth to his music, like being held in the arms of a loved one who has already passed on. Gene gives the listener permission to cry, to grieve, even if it's for the person we used to be. His music is not an escape, but some sort of liminal space. A corridor. A strange nirvana.

Sometimes, I dance to Gene’s music alone in the living room. I make myself dinner and babysit a glass of wine and scratch things into a notebook and pretend it's poetry. I smile at strangers on the street and light candles for the unliving and hug the ones I love and let the cicadas sing me to sleep. I go to work and stain my teeth with herbal tea and stuff envelopes with magazines, listening to the same few songs on repeat, always waiting for the phone to ring.