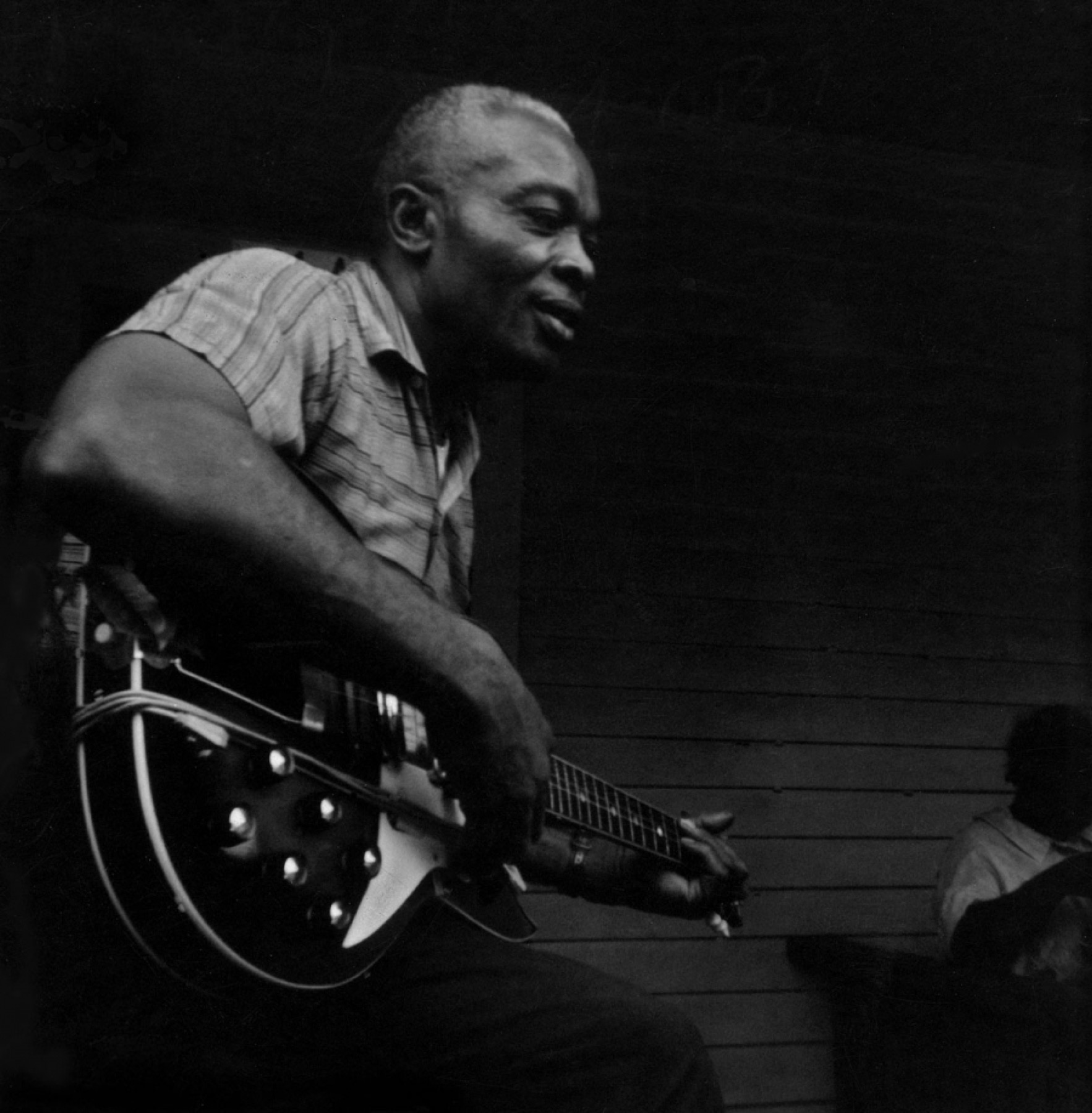

Photograph of Buddy Moss by George Mitchell

HOOT YOUR BELLY

By Brian Crews

Beginning in the 1960s, the folklorist George Mitchell spent the better part of two decades canvassing the rural reaches of the American South in search of the blues. His legendary career is one marked by passion and drive. As a young man, Mitchell roamed the back alleyways of Atlanta, his hometown, and later worked as a photographer for the newspaper in Columbus. On the weekends, George and his wife, Cathy, would drive around rural Georgia seeking musicians to record, often crossing stringent racial divides in the process. Like many folklorists who wandered the Southern states making field recordings, Mitchell spent a significant amount of time in Memphis and the Mississippi Delta. It was there he recorded and befriended blues giants Fred McDowell, Sleepy John Estes, and Furry Lewis, among others.

Captivating as his Delta recordings certainly are, it is Mitchell’s work documenting the uncharted, wildly singular blues culture of Georgia’s Lower Chattahoochee Valley that remains, arguably, his most lasting musical contribution. In many ways, these recordings are the only documentation of a once-thriving American musical tradition drawing its last defiant breath.

Along with his contemporaries, and fellow Georgians, Fred Fussell and Art Rosenbaum, George Mitchell’s work preserved an important aspect of Georgia’s vast musical landscape. Over the years, his field recordings have been issued by a number of labels, including Arhoolie, Rounder, Testament, Southland, and Swingmaster. Most recently, Fat Possum reissued a comprehensive box set entitled The George Mitchell Collection. Mitchell has also authored several photography collections, including the book Mississippi Hill Country Blues 1967, documenting his and Cathy’s first trip to the Delta.

I had the great opportunity to visit the Mitchells last March at their home in Fort Myers, Florida. The rest of George’s remarkable story is told here in his own words.

When did you first hear the blues?

The earliest experience I had that introduced me to the blues was at my friend Roger Brown’s house. We were turning the dial on his tiny little radio looking for the latest Elvis songs, like people in eighth grade were doing back then, and we suddenly heard a voice and I stopped—Turn that . . . what is that? Who is that? It was a black radio station and they announced, “This is Muddy Waters,” and I thought, Man, I love that sound. I loved it so much that I started listening to it—stopped looking for Elvis songs, started looking for Muddy Waters songs, Howlin’ Wolf songs, Sonny Boy Williamson songs. Only two places you could hear ’em was WAOK—Piano Red, a great Atlanta blues artist, was a disc jockey—and WLAC in Nashville. I had my little radio with wires up in the trees and everything out back where I could pick up a place at night that would play nothing but blues. And they played a lot of people like Slim Harpo, John Lee Hooker, Lightnin’ Slim—oh, I just loved that music.

I started going down to Central Record Shop on Decatur Street in Atlanta. Guy who owned it was a white guy named Bill, who was a great salesman—Hey man, listen to the newest Lightnin’! So I’d be buying the singles of these later blues artists as they came out. Not long after that, Sam Charters, who was a jazz writer primarily, wrote a book on an earlier form of blues that I didn’t know existed called The Country Blues. That’s what the old time blues is often called, the blues that predated the blues I was listening to, the main popular music of the day for black people in the twenties, thirties, and forties. So I got introduced to that, and then Charters put out a record in conjunction with the book. Roger bought that record and he called up and said, “Hey Mitch, listen to this,” and he played “Low Down Rounder” by Peg Leg Howell, who was from Atlanta, over the phone. I said, “Hey, man, that sounds good.”

After reading the book I started looking around Atlanta for some of these old time blues singers, but couldn’t find anybody. Sam Charters had done most of his work in Memphis, spending a lot of time with Will Shade of the Memphis Jug Band and some of those folks up there—Furry Lewis, Gus Cannon. And so my friends and I decided we’d go up to Memphis and hear this in person. We were juniors in high school, seventeen years old. We stayed with my aunt; it’s what we had to do for our mothers or whatever. Then we went down to Beale Street—this was the old Beale Street, not like it is now—and thought, Well we gotta find Will Shade someway. We went into this drugstore and asked somebody, and they said, “Nah,” they didn’t know him, “Go ask Whiskey,” and they pointed him out. Whiskey said, “Yeah, I know him. Want me to take you to him?” We found him so fast; he lived down an alleyway just around the corner from the drugstore. It was this very old, very broken down, dumpy apartment house with these very old stairs. It was my first time in a place like that. We followed Whiskey up the stairs and then heard some music behind the door. Whiskey knocked—“Somebody here to see you, Will”—and the door opened and there was Will Shade, head of the Memphis Jug Band who we’d heard on the Country Blues record doing “Stealin’, Stealin’.” He immediately stuck out his hand and said, “Son Brimmer’s the name”—that was his nickname—and in the room was Charlie Burse, who was in the band, with his four-string tenor guitar. They were practicing to go play in the lobby of the Peabody Hotel about twenty minutes from then. And so we watched ’em, listening to ’em play “Kansas City Blues.” Here we were, these seventeen-year-old kids in Memphis listening to this great music that we had only heard a little bit of on records.

When you came back to Atlanta from those early trips to Memphis, was that when you found Peg Leg Howell?

I had looked for him before going to Memphis, but, as I learned in later years, especially, it’s almost impossible to find unknown blues singers in big cities just by walking around asking. In a small town everybody knows everybody, but that’s not the case in big cities, which is probably why I found no one in Atlanta. But, later, I had some friends from college who were having this sort of rummage sale in Decatur, and most of the customers were black, and so I decided to just ask some of these people if they know anybody. Around the second person I asked did know somebody: Willie Rockomo and Bruce Upshaw. These were unknowns. They told me where I could find them, and I found them. They came over to my family’s house and recorded, and they were very good. Bruce Upshaw blew the harmonica, Willie Rockomo played guitar.

Here, I had found somebody in Atlanta, so I knew they were definitely around. Then I asked if Bruce and Willie knew anybody else, and they gave me somebody’s name, and I asked, “How do I find them?” They said they didn’t know, but to ask around on Decatur Street, which was one of the main black drags in Atlanta at the time. We stopped at a place called Shorter’s Barber Shop, me and Roger Brown and another high school friend, and nobody had heard of them. So I said, “Any chance you ever heard of Peg Leg Howell?” Boom. Everybody had heard of Peg Leg Howell. I had people crowding around me, “Want me to take you to him?” I said, “Man, I’m about ready to meet Peg Leg Howell!” A couple of guys took us to him, down a dirt road. Everything was still segregated, and most of the roads in colored neighborhoods were unpaved. (This is where the Braves Stadium is now.) He took us up there to a little tiny house, took us in, and I met Peg—that’s what people called him. He was a very old man then. He had no legs, and he couldn’t see very well. And he had not played since 1934 and this was ’62. But I had a guitar with me and he took it out of my hands and strummed on it some and sang some. He had quit playing because his fiddle player, Eddie Anthony, died in 1934, and they were so close he just couldn’t play anymore.

And you recorded him then?

Well, I had decided at this point that I was going to go work in Chicago for Delmark Records, cause they were one of the first ones—a small company—to put out one of the old timers, Big Joe Williams. They said for me to record him, and they’d pay for the studio, whether he’s ever recorded or not. So I worked with him every day. It’s kind of sad in a way—he had these long fingernails, and they’d hit against the guitar and make a rattling sound. That was one of the first problems. He could still sing some, but he hadn’t played guitar in so many years. So I said, “Peg, you need to cut your fingernails tonight.” Got there and his fingernails were not cut. So the next day I decided, Well, I got to cut his fingernails. But they were calcified, and I could not cut them. With all my strength, I could not cut Peg Leg Howell’s fingernails. The solution that I came up with was to get some foam rubber in the shape of the guitar and tape it on so his fingernails would be hitting against the foam rubber. But there would be other problems—he was almost blind and he would get his verses confused. I’d write his verses down on a big poster board and hold them up. I’d never been through anything like this before.

But Peg just worked, worked, and worked—at the age of seventy-six—to get things together. Finally, we went to the studio and figured out he couldn’t play in a chair—he had to play in a bed because he couldn’t sit up in a chair right. So we had to carry a rollaway bed up to the second floor where the studio was. He still never had it together, but it’s a moving record. That was my first experience recording a Georgia bluesman and a legend and one of the all-time greats from Georgia. He was just so nice, too. He gave me a picture he saw me admiring on his wall all the time. It’s of Peg Leg, Eddie Anthony, and the guitar player Jim Hill. Peg Leg Howell and his gang standing there. He wanted to give that to me.

Jim Bunkley; Georgia Fife and Drum Band. Photographs by George Mitchell

Jim Bunkley; Georgia Fife and Drum Band. Photographs by George Mitchell

You spent time in the late sixties recording artists in Mississippi and Tennessee. What was it that brought you back to Georgia?

I went to graduate school in Minnesota. I had a degree in Journalism. I was applying at newspapers in the South and I got a job in Columbus, Georgia, working for the Columbus Ledger. This was 1968. So we moved to Columbus, my wife Cathy and I. We’d been living there for a good long time. And then one day—we’d lived there for six or seven months— I said, “Man, why don’t we go out to these small towns around here and see if there’s any blues singers?” So we took off looking.

First person we found was Jim Bunkley in Geneva, Georgia, and he lived in this tarpaper shack. No other house around it. He was so friendly and invited us in. Just ready to play. And we went back a lot. It was always exciting to go to Jim Bunkley’s in Geneva, Georgia. His wife actually sang a couple of songs, sometimes others would come in. Bunkley told us about other people. For a number of months there—in our spare time, in the evenings after work, or on weekends—we would go to towns actually pretty far from Columbus: Waverly Hall, Talboton, all down in there, and we never went to a town without finding a blues singer who could do at least a few great blues songs.

The ones I recorded the most were Bunkley and George Henry Bussey of the very musical Bussey family of Waverly Hall, Georgia. The Busseys even had a fife and drum band. People thought those musicians were just in Mississippi, where I had recorded some old-style music, like West African. But there they were, the Bussey Family, doing old-style fife and drum music. It was unbelievable. And then George Henry told me about his niece Precious Bryant, who ended up becoming quite well known. There were so many great musicians at that time. Bud White would do “Sixteen Snow White Horses”—old songs you’d never heard of before. We hadn’t even thought about looking there and lo and behold there it was, rich.

That’s amazing. So it was a pretty undocumented region then?

It was totally undocumented, as far as I know. No one from that area had recorded during the heyday of blues recordings during the twenties and thirties and it had a style to the music—a frolicking sound. They would play at frolics and maypole dances. Pole platting. That sound was behind the style that was unique to the area. But they never recorded it because none of the big companies ever came to Columbus. They’d be in Atlanta, but there was no main road to Atlanta. These people were extremely poor and isolated, so this was the first time they had been documented. It was really a thrill. And once the record companies started hearing them, they wanted to issue them.

Dixon Hunt and his wife. Photograph by George Mitchell

Dixon Hunt and his wife. Photograph by George Mitchell

Was that when you first came across Cecil Barfield?

No, that was later. I can remember the first recording session. We had to record at a house in Bronwood, down from Cecil’s house because Cecil didn’t have electricity. We finally got everything set up, and Cecil came in and said “George, we gotta go someplace else.” What he was worried about was that his checks he got from the Welfare department would be taken away from him because he was making money from doing something else. So we moved over to Plains, Georgia, to a sharecropper’s shack on somebody’s plantation. Cecil had his old electric guitar, beat up old thing, beat up old amp, but man he could make that thing talk. And it was quite a recording session. I mean he was really going good. Even did a song called “William Robertson Blues.” He told me he wanted to go by that name, because he did not want people to find out he was making any money—although it wasn’t a lot of money—and didn’t want his picture on the record. He was a very superstitious man and spent most all of his record earnings on root doctors, taking off spells and everything. ’Cause he felt like—and who knows, maybe he’s right—that somebody could turn the album over and stick a pin in it if his picture was there and hurt him, kill him. For the album cover, my wife drew a picture of him from a photograph I had taken that you could hardly see, it was so underexposed.

He was receptive to you wanting to record him?

I was always welcome by the black artists. The only bad experiences I had were with the white people that lived in the area. We were about finished, but I hadn’t interviewed him or anything for the liner notes. And I wanted to record him some more, when someone pulled up in a pickup truck and a white man came in and said, “Hey, y’all gotta get outta here. Now.” And I said, “Why?” And he said because this house belongs to his father who lives in that plantation house up on the hill and he said, “See it?” He said, “Get out. Now.” And he left. I said to Cecil, “I’m pretty good at talking to all kinds of people, I believe I’ll go up there and talk to him and explain to him what we're doing.” And Cecil said, “George, I don’t mean to hurt your feelings or anything, but I don’t think you’ll succeed.” I said, “Well, we’ll see.” And I went up there and this man stomped out of his house. (This was at the time Jimmy Carter was running for President. The week before, on the cover of one of the newsweeklies, it talked about the racial progress in Plains.) The man said, “Listen buddy, niggers and white people aren’t in the same house down here. We don’t do that. Get the hell outta here. Matter of fact I’m gonna call the sheriff right now.” So I said looks like Cecil was right, better get the stuff outta there. Cecil said to follow him to someone else’s house who doesn’t live on the plantation. We went and I interviewed Cecil.

He was quite a great musician, an unusual musician, and he was a folk artist also; he made things out of Coke cans, like airplanes and things. He was a very, very intelligent man. We’d stay up all night talking sometimes. He was a real philosophizer. The way he put things would be so amazing, but he wasn’t educated at all. Lots of People from Germany, from Italy—after they heard the record—wanted him to come play. And he would not leave; he was not about to go anywhere. He wouldn’t even come to Atlanta, much less Germany or Italy.

Guys like Cecil Barfield were some of the last real country blues musicians. Is that why you quit doing field research?

Well, it finally started getting to the point—when I was working for the Georgia Grassroots Festival—that I’d be on the road ten hours a day, six days a week, looking for blues musicians and I might find somebody once a month and, you know, they were dying out. Young people were not keeping it going—reminded them too much of sharecropping times and everything. I decided it was time to do something else and basically stopped doing field research. So I said, let's see about organizing this huge blues festival; we’ll call it the National Downhome Blues Festival and get the best blues artists from every state in the South, and from the North—Chicago, St. Louis, Detroit, everywhere—and get them all together for one weekend. And I was able to pull it off. It was a big success. There were people lined up from around the block to get in, and the musicians were all at their best because they were playing for their colleagues, their best-known blues colleagues. So that was a thrill. That was in 1984. And then I pretty much stopped doing field research.

Now, when I came down here to Fort Myers four years ago, I said, well, I’m gonna see if I can find Blind Lime—the name I made up to go on Blind Lemon—just to see, ’cause nobody done any research down here, period. I didn’t know what had been here. I found out there were blues singers here, down in South Florida, just like everywhere else. Everybody knew their names and everything, but of course they’re all dead and gone.

George Mitchell

George Mitchell

Read more about Georgia blues in our Georgia Music Issue, on newsstands now.