Inside Broc’s Cabin

Sub Pop co-founder Jonathan Poneman on Rein Sanction

By Noah T. Britton

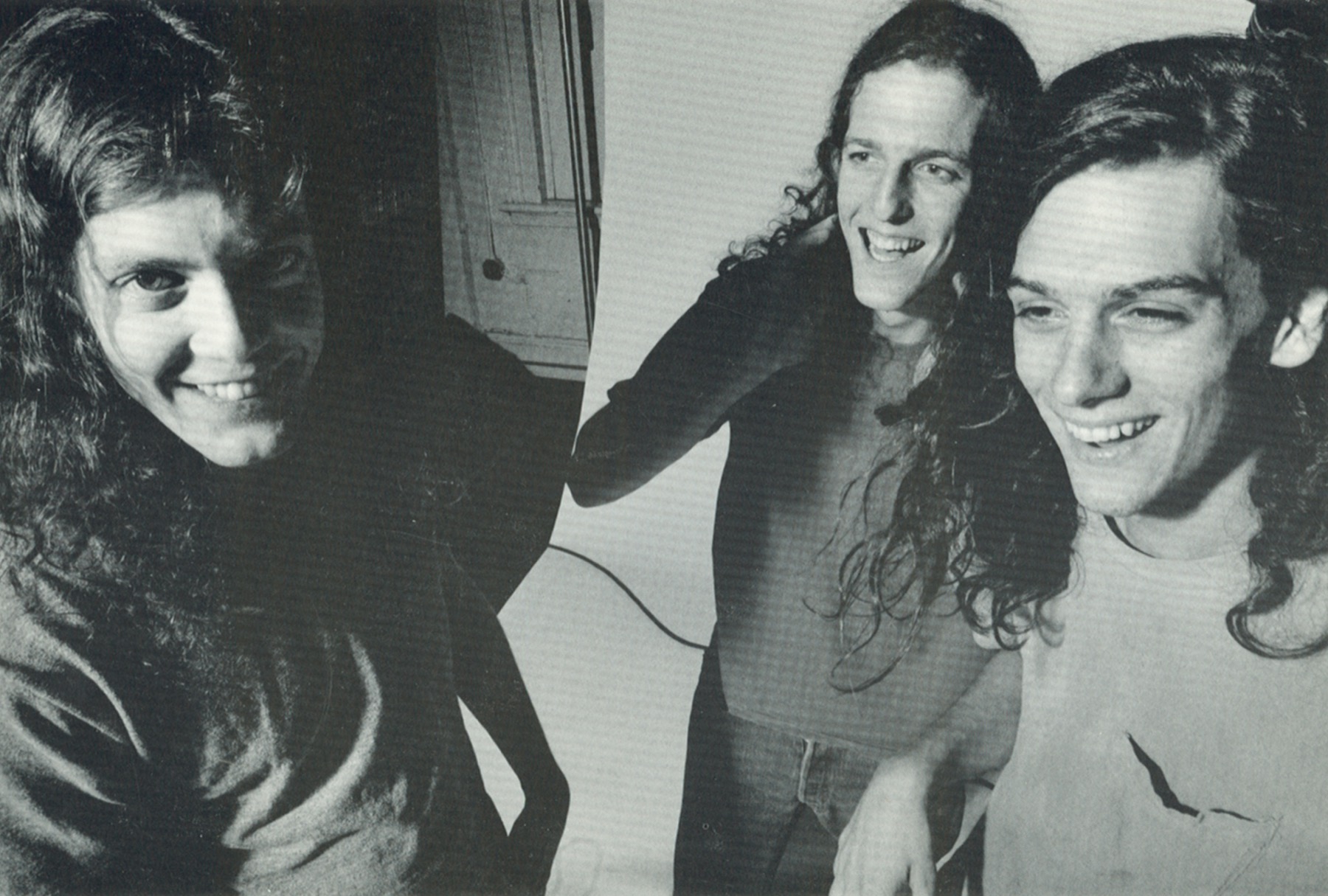

Courtesy Sub Pop Records

Soon after Bruce Pavitt published the first issue of the fanzine Subterranean Pop in 1980, a group of nearly teenage kids in Jacksonville, Florida started making music under the name Rein Sanction.

Brothers Mark and Brannon Gentry joined their neighbor and childhood friend Ian Chase, sifting through their parents’ records and bypassing the native influence of Jacksonville’s Allman Brothers in favor of Jimi Hendrix’s mind-bending riffs. Mark fronted the band with his guitar and vocals, with Brannon on drums and Ian on bass.

Rein Sanction’s evolution continued to parallel the birth of the grunge scene happening across the country, promoted by the Seattle-based label that grew out of Pavitt’s now-legendary zine and his curation of regional talent. Pavitt founded Sub Pop with Jonathan Poneman in 1988, both Seattle transplants united in their zeal for Soundgarden’s early club performances. The label’s initial slate consisted almost exclusively of acts from the Northwest, including the first releases by bands that would become synonymous with the grunge movement: Soundgarden, of course, Green River, and Mudhoney. “Focus on the Northwest, be a Northwest record label,” Pavitt recounted to rock historian Gillian G. Gaar, “the same as Motown was a Detroit label.”

Rein Sanction released a self-titled EP the following year, characterized by a frenzied, grainy density that would draw incessant (and unfailingly dismissive) comparisons with J Mascis’s Dinosaur Jr. Mark’s bleak, haunted vocals thread through scenic references to nature, evident in songs like “Limestone,” which reappeared on the band’s subsequent album. Throughout the decade of Rein Sanction’s emergence, Jacksonville was in the throes of a suburban sprawl that left parts of the inner city abandoned in favor of strip malls and resort communities. It’s the muted dystopia of their youth that might connect the band—three wiry, long-haired kids, pale despite the Florida sun—to the distant scene that defined their sound. Rein Sanction grew up amid the rapid modernity that grunge rebelled against, processing it all from their parents’ basement or maybe the garage where they first experienced the electric crackle of feedback.

Somewhere between howls of “Touch Me I’m Sick” and the impending upheaval of Nirvana’s Nevermind, Sub Pop’s co-founders met Rein Sanction at a party in Jacksonville. The band’s debut album, Broc’s Cabin, was released by Sub Pop in March 1991. Often heralded as the group’s finest work, the album thrives on wide-open, wall-of-sound dissonance, with standouts like “F Train” pitting Mark’s world-weary lyricism against Ian’s steamrolling bass. The album’s title track is an act of sonic prescience, hinting at the band’s unsettled fate. Halfway through, just as the song teases a subtle end, Mark doubles back with an earnestly introspective verse, high-pitched feedback and dueling drum giving way to a completely revitalized second half. The song reaches its breathless conclusion, and once again, we resist oblivion.

Rein Sanction would go on to release one more album with Sub Pop, the Jack Endino–produced Mariposa, before its abrupt and mystifying dissolution. The band maintains a dedicated cult following, mostly active on blogs and forums, with confessional threads offering a final attempt at rekindling Rein Sanction’s warmth. “It’s very easy for this music to get lost,” Poneman said during a Zoom call in July. “I don't want those records to be forgotten.”

Exactly thirty years after the album’s release, I spoke with Sub Pop co-founder Jonathan Poneman to discuss the legacy of Broc’s Cabin and the process behind its creation. We revisit Rein Sanction’s origins and the cross-country route of the band’s Up South trajectory.

Noah Taylor Britton: I’m curious to know how this Seattle label came to find this band in Jacksonville, Florida.

Jonathan Poneman: So, you know Rough Trade, the record store. There’s obviously a Rough Trade label. There was a Rough Trade distribution company, and Terry Tolkien, I think he was working in the distribution area at the time. He had great taste in music. He later went on to work at Elektra Records. But he tipped us off to this band of teenagers who lived in Jacksonville, Florida.

They had put out an EP and he got the record from Kramer, who was the founder of Shimmy-Disc. Very influential record label. Kramer also produced [Broc’s Cabin]. Terry turned us on to it, and I loved it immediately because historically, when people write about this record, there's a lot of references to Dinosaur Jr. And while there is definitely, you know, J [Mascis]’s kind of sound there, there’s also a larger SST [independent California-based label] influence. I hear some of Curt Kirkwood of the Meat Puppets, a lot of his early guitar stuff. Greg Ginn, obviously. There’s even some free jazzy, Blind Idiot God–type, you know. And this is what was happening in the late Eighties as far as progressive music went, and those kids really soaked it up.

So Bruce [Pavitt] and I flew down to Jacksonville, stayed in Jacksonville Beach. I think we actually ended up seeing them at a loft party. We were just enchanted with them because there was, from my perspective, a real Southern Gothic, expressionistic quality to music that went beyond influences. There was this real longing, this kind of mysterious, brooding quality to the music. It felt very regional to me, you know, as a Midwesterner trying to make sense of the South.

NTB: I was reading an interview with Mark Gentry, and he talked about how he started taking music seriously when he got into jazz and began to study classical music. That convergence of influences is something that I associate with Southern music.

JP: I also think that virtuosity in Southern rock is something that has never been shied away from. In the Northwest, there are plenty of great musicians, but Northwest rock is more primal.

I haven’t spoken to Mark in a very long time, but he was unashamedly a virtuoso, as was and is Ian Chase. And Brannon is a functional drummer—he’s a good drummer, actually—but it was the interplay between Ian and Mark that drove the musicality of that band in its early years. You know, if you listen to Rein Sanction’s later records, it sounds sedate, and it sounds tamed. It lost a lot of that wildness and the virtuosity.

A lot of the grunge bands, it’s more about the feeling and the attitude. And that’s important. That was important for the Rein Sanction kids as well. But they also were unashamedly flashy. Not in a showboat sort of way, but they were willing to fit in too many notes if it was to express what they wanted to convey. And I think they had a broader mission than just making a cool pop song.

NTB: There hasn’t been much online about the band, but in the few reviews that I’ve seen, they’re constantly described as “soulful.” I think that’s an interesting distinction to make between the Northwest and then the music coming out of the South, the element of soul in it.

JP: Yeah, and it depends on your definition of soul. Rhythm and blues music has played a heavy role in all forms of Northwest rock, be it the Wailers and the Kingsmen or Heart or Jimi Hendrix. There’s a lot of an r&b aspect. But the soul that I think you’re referencing is a vulnerability. If you listen to the first Meat Puppets record, you can hear that Curt is going to be a dazzling guitar player. There’s bits of dazzle in it. But songs like “Walking Boss,” it’s got, like, fuck-all attitude. You wouldn’t really find that in Rein Sanction, for better or for worse. They were emotionally invested in a very honest way. Maybe a lot of it had to do with their age and their choice of drugs.

NTB: Mark Gentry talked about this kind of freeform jamming being part of their creative process. I wanted to see if you knew if that was relevant to Broc’s Cabin as well, if parts of it came to be through spontaneity?

JP: I caught up with Ian a couple of days ago, and he still lives in Jacksonville. He says that he’s tried to get himself and the brothers to play together again. Reconstitute or try to get back what they had. It’s one of those things, you know, lightning in a bottle. You can’t capture it.

One thing I will say is that the jamming that they did, that’s something that, stereotypically, people of my generation associate with Southern rock, like the Allman Brothers tradition and stuff like that. Obviously, there are bands who jam now, but when Rein Sanction and bands like that would go at it, there was a desire to grate boundaries. A lot of the bands of that era would go further and try to conjure all sorts of musical combinations and dimensions. And I think that the Gentry brothers and Ian just took it as far as they could, and they could go far because they were gifted players. I know that their approach was a lot less linear than a lot of the grunge bands.

NTB: I also feel like there’s an element of intentionality in their work. I’m really fascinated by the decision to open the album with “F Train,” because you get that extended distortion at the beginning of the song. There’s just an element of suspense before you get into the album, which I think is cool.

JP: I talk about their otherness and their virtuosity and trying to make a distinction between their being a Southern band and not a Northwestern band. But the fact of the matter is that they were part of the greater American music consciousness of the time. To this day, Ian is tired of hearing Dinosaur Jr. comparisons.

Dinosaur Jr. [was] a great band. It’s not surprising that a dollop of what they do would end up in what Rein Sanction was about, because besides being great players, they were great listeners.

NTB: It seems like their entire career was kind of dogged by comparison to other bands. I’m wondering how you see the band’s legacy and their impact on grunge?

JP: You’ve listened to those records. Do they merely sound like something else, or do they have a mysterious quality?

NTB: I was listening to a few Dinosaur Jr. tracks after reading the comparisons, and [Dinosaur Jr.] seems a bit more subdued to me.

JP: Yeah, definitely. In [Rein Sanction’s] particular case, I think those records are really special. You know, Southern Lord reissued their first [self-titled] EP. Mariposa, which is the second Rein Sanction album on Sub Pop…Jack Endino produced it, who did Bleach and Superfuzz Bigmuff. The record is definitely Rein Sanction and there are some beautiful songs, but there’s more of a Groundhogs/Hawkwind in the musical breaks. Nothing overt, but it’s Jack bringing his sensibilities to their band. One can only do that so much, because the band’s internal dialogue is so involved that no matter what a producer tries to contribute, it’s still going to be what it is.

After that record, things started to unravel. As I understand, there were personal issues. But those two records—three, including the EP—capture Rein Sanction at their climactic best.

NTB: I wanted to get your perspective on Kramer and his contribution to the album.

JP: Kramer’s greatest gift is his ability to listen, and he didn’t try to impose anything on them. Speaking of Broc’s Cabin, it’s distorted and explosive, but there’s this fragile beauty at the heart of it that he was able to not just let it coexist, but he was able to even nurture it. I think that’s a producer’s gift. You can’t fake that with studio gimmickry. I think that’s something that you’ve got to be able to hear. That means listening. Particularly for music like that, which is not reliant on a performance like the great vocal take that’s important in other kinds of music, in pop music. It’s crucial. But for what they do, atmosphere contributes as much as performance.

NTB: I wanted to talk about the title track on the album. I think it represents what you’re talking about, that meshing of intensity with vulnerability.

JP: There’s a reason why it’s the title track. I know that they all loved that song and they were proud of it. But I also think that it captures the essence. It’s like a snapshot of where they were at that time. It’s like a pop song in that it’s a distillation of certain emotions and a certain place in time.

NTB: I was fascinated to learn the timeline for this album, because this came out in March of 1991. You have Nirvana’s Nevermind coming out later that year. But it’s my understanding that the first half of that year was a relatively tough time in Sub Pop’s history.

JP: Yeah, totally.

NTB: I think it’s interesting that you are assuming the risk of a debut album from this small band that’s outside of the Northwestern focus of Sub Pop at that moment.

JP: The thing is, Broc’s Cabin had been sitting around for some months before we put it out. Bruce and I got real self-conscious, I think is the best way to put it, of turning into self-parody. We parodied ourselves right off the bat, so on one level, what’s to be afraid of? But, at the end of the day, there’s marketing gimmicks and then there’s the music.

Bruce, much of what he was interested in and remains interested in, is regionality in popular culture. Sort of the statement we were making is not, “Here is the Mudhoney of Jacksonville.” But we were saying, this is a band that is obviously part of a greater milieu that is vibrant. And they’re different. They’re not, you know, the Smashing Pumpkins. They were something unique, they were geographically unique. Now there are tons of bands from Florida, but at the time, there weren’t that many. I mean, there were other styles of music, other communities represented, but for underground rock music of a certain vibe, they were unique. Also, Terry, the person who turned us on to them, was a great passionate salesperson. He went on to become a successful A&R person. I’m sure his being their champion pushed us along.

We were, in one sense, senseless and fearless. But most importantly, we were driven by our love for the music. And that’s what would put us in these stupid, ill-considered, risky positions for the sake of something we thought was exquisite beauty. We were younger then. I’m going to be sixty-two years old. Back then, I was in my twenties. Acting stupid was your birthright. I don’t know if I’d have the courage to be so stupid now. Who knows?

NTB: I have a lot of respect for Sub Pop’s origin and focus on these hyperlocal sounds. Our editor, Danielle A. Jackson, talks about the South as a marginalized region. I’m picturing these three guys, these childhood friends, in a basement in Jacksonville, Florida, making this music. It feels like a reminder of the importance of these oftentimes overlooked regional spaces that aren’t New York City or L.A.

JP: That’s true. I’m bedeviled by the horrible things, the atrocities, that have taken place in that region. But there’s also the greatest wealth of beauty. As far as culture and tradition, there’s no other place in the United States that can compare.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.