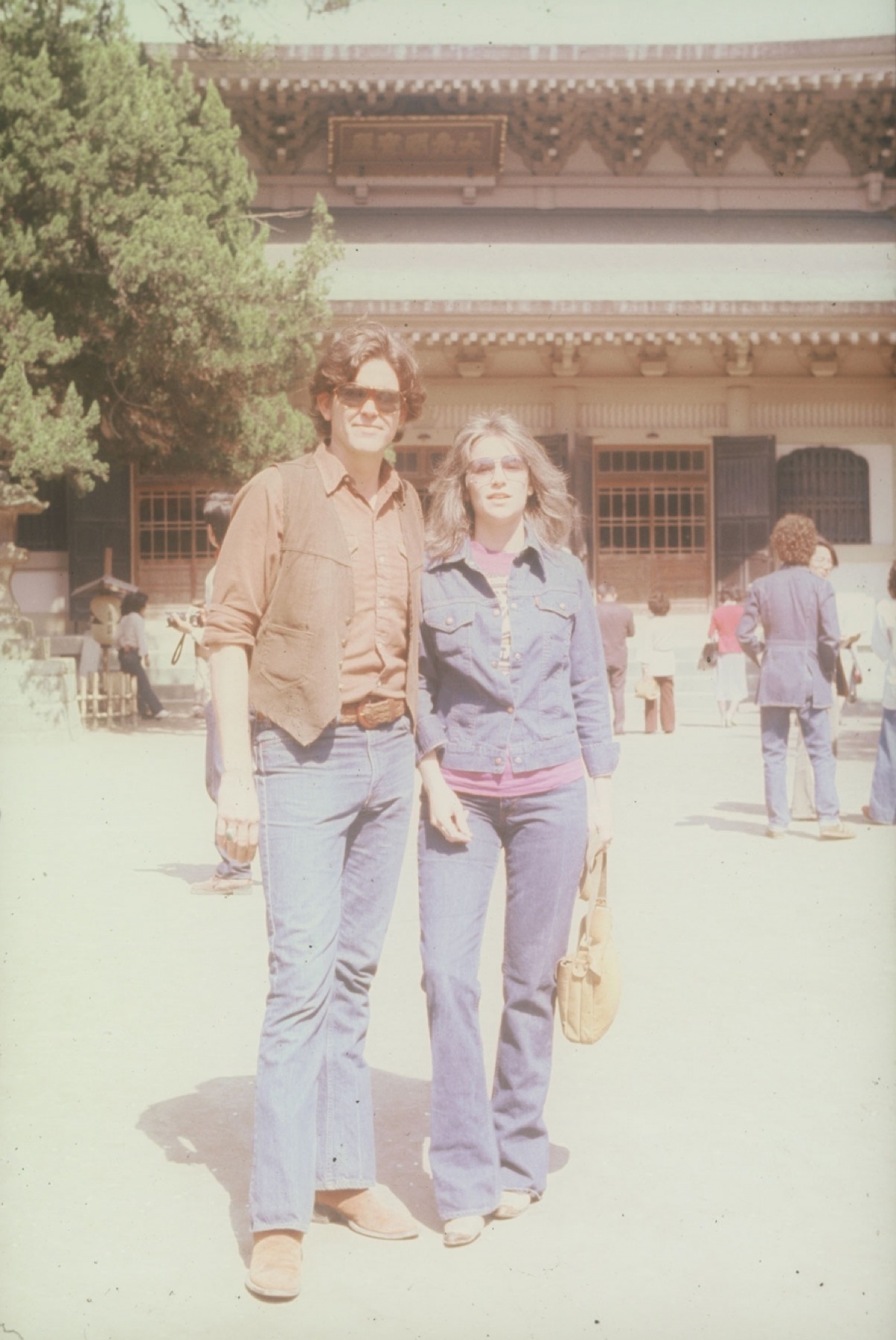

Guy and Susanna Clark in Japan. Image courtesy of Tamara Saviano

It Was What It Was

By Jonathan Bernstein

Over the last several decades, Tamara Saviano has seen almost every facet of the music business. She’s produced tribute albums for Jackson Browne (Looking Into You: A Tribute to Jackson Browne) and Stephen Foster (Beautiful Dreams: The Songs of Stephen Foster); worked as a journalist, profiling artists like Dolly Parton and George Strait; formed her own songwriting publishing nonprofit in Nashville, American Roots Publishing; and served as publicist for legendary artists like Kris Kristofferson. By her own account, the hardest thing Saviano ever did was write a biography of her close friend Guy Clark.

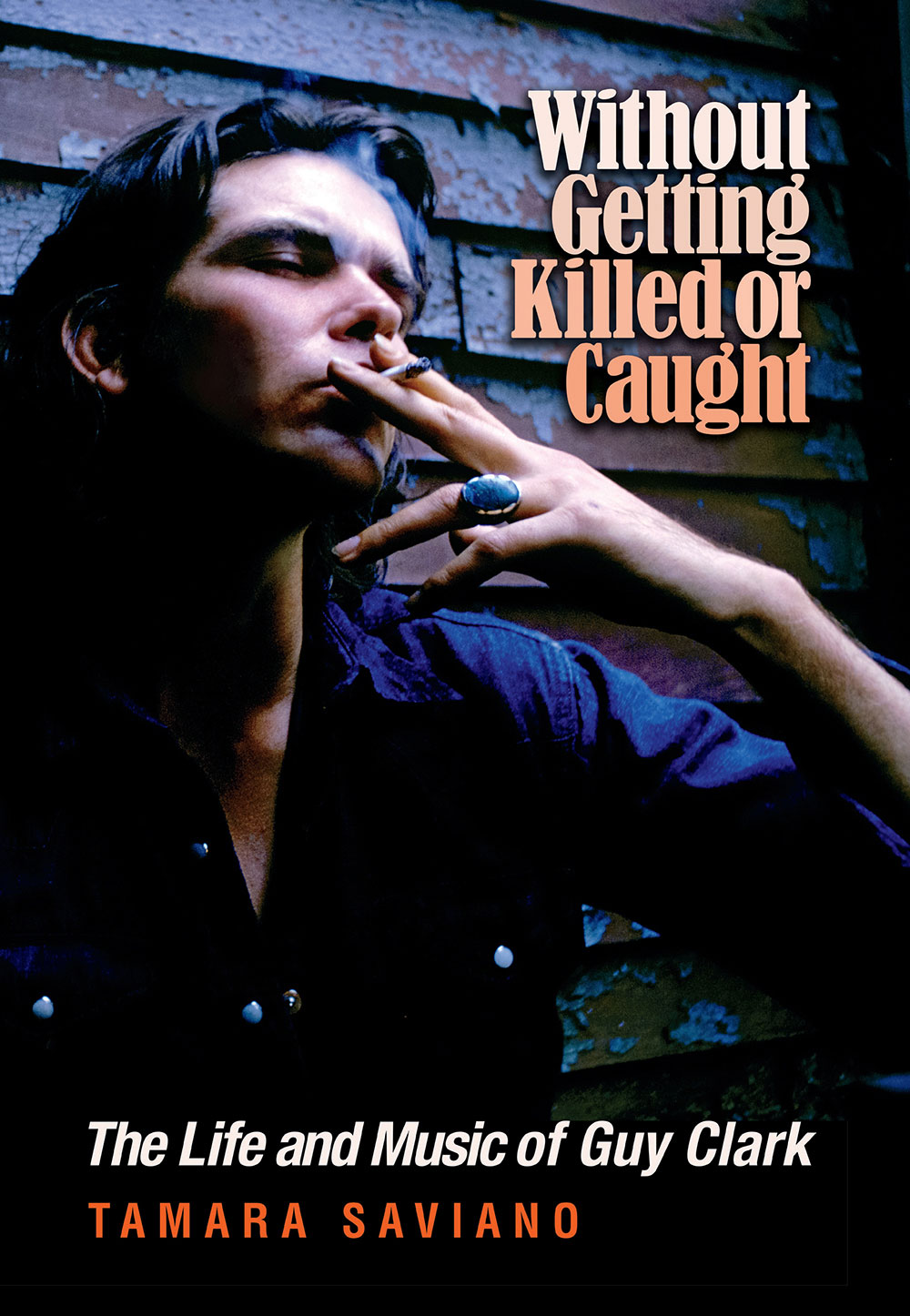

Without Getting Killed or Caught: The Life and Music of Guy Clark, released today, is the first-ever biography of the Texas singer/songwriter. Although the book is published just five months after Clark died—on May 17, from lymphoma—Saviano worked on the book for an overwhelming eight years, during which time she also served as the artist’s publicist. “The only reason I kept at it was because I didn’t want to let Guy down,” she says.

Fans of Clark’s music will be grateful to Saviano for completing the book, which is crammed with personal anecdotes from the likes of Rodney Crowell, Steve Earle, Verlon Thompson, and Emmylou Harris, reading at times like a who’s who of late twentieth-century Nashville. Without Getting Killed or Caught is a moving, revealing portrait of an artist whose literary storytelling set the standard for several generations of country songwriters. Saviano’s close relationship with Clark helped the notoriously guarded singer open up about all aspects of his turbulent life.

“The moment I turned on the recorder, Guy opened his mouth and spilled stories that many of his closest friends hadn’t heard,” writes Saviano. “He ventured down roads I never believed he would, not tiptoeing around the thorns but barreling right into them, scratches and cuts be damned.”

Regular readers of this magazine will already know Saviano’s name associated with Clark; she wrote a profile of him for the 2014 Texas Music Issue, which featured Clark and his late wife, Susanna, on the cover. Earlier this summer, I talked with Saviano about her new book.

That you were Guy’s publicist at the same time you were finishing this book must have made for a crazy last few months.

That you were Guy’s publicist at the same time you were finishing this book must have made for a crazy last few months.

Guy was telling me for at least a year and a half before he died that he would not be here when the book came out. Early on, I would try to joke him out of it. I would say, “Don’t give me that shit, Guy. I’ve done way too much work for you to die on me now,” and we’d laugh.

But when he ended up in a nursing home earlier this year, our conversations turned to me assuring him he had done all the heavy lifting, that I could take it from here. About a week before he died, I brought my page scripts with me and asked if he wanted me to read anything to him. I’m paraphrasing, but Guy said, “I’m sure you wrote the book that you were meant to write. It’s perfect the way it is.”

Had you handed in your first draft of the book before Guy passed?

I handed in my manuscript in September 2015. The day that Guy died, my manuscript was on its way to the press. We had to stop everything because I needed to write an epilogue.

The epilogue is such a moving story.

That day, I was in Phoenix. Guy died early Tuesday morning, and the Monday before Rodney Crowell called me and said, “You need to get on the next plane home.” I booked a flight for 6:30 AM the next morning, and I didn’t make it. When I got home Rodney called me and said that they had met with the funeral director and that they were going to UPS Guy’s remains to Santa Fe. That’s when Verlon Thompson said, “Can I just drive him out there?” And then everybody jumped in said, “I want to go. I want to go, too.”

So Rodney told me the plan. [Guy Clark had requested that his remains be turned into a sculpture by his friend, the artist/musician Terry Allen.] I called Terry Allen. And Rodney started calling Guy’s friends. By the time we made it to Terry’s in Santa Fe and were sitting on the patio, it was like this sense of relief that we’d made it, that Guy was where he was supposed to be. We were all together. Guy would have loved it. He would have loved it.

Were there times when you felt conflicted about what to include, given how close you were with Guy?

There weren’t, and that’s thanks to Guy. He said to me numerous times: “I want the truth. I’m not out to make my life prettier than it is.” A month or so after Susanna died [in Summer 2012], he handed me all of her diaries. I said, “Guy, have you read these yet?” And he said, “No, and I’m not going to. These are Susanna’s truths, and you’ll use them how you see fit.”

Guy was such an honest person about his own faults. He wasn’t one to put himself in the best light; he was comfortable with being human. He really did try to do the right thing most of the time, but he was comfortable having flaws. So I felt comfortable writing about them.

How did you navigate writing about Susanna’s decline after Townes Van Zandt’s death?

Rodney and Guy talked a lot, even after the fact, up until Susanna died and afterward, about Susanna’s pain in her back, and whether she really had pain and whether she should have seen more doctors. I talked to a doctor who I can’t name but who knew what happened to Susanna, and he told me that absolutely she had a major issue with her back, that it would have been really painful. But he also said it is true in all the medical literature, that we hold grief in our backs. So was a little bit of both going on? Maybe.

There was no doubt that Susanna and Townes loved each other deeply. In this book, I tried to convey that Guy was such a stoic Texan, a “stand up and be a man” type of guy, and Townes and Susanna were much more vulnerable and sensitive. Townes, being so close to Susanna, took a lot of pressure off Guy, and he admitted that. Guy didn’t have to be that person for her because Townes was that person. Susanna basically had two husbands.

Reading about their unique relationship reinforces that the three of them were operating on some higher plane or alternate wavelength than the rest of us.

It’s very powerful. I had asked Guy several times if he was jealous of the relationship Townes and Susanna had. He said, “No, he was always in love with my wife, and she was always in love with him. It just was what it was.”

Did you have any revelations about Guy during the process of writing this book?

Several. The first was when I realized Guy was really, really protective of his sisters, Caroline and Jan. He just loved them and took care of them. He also had these strong grandmothers and a strong mother—and then Susanna—so another thing that really stuck with me is how Guy loved strong women. Some men are intimidated, but Guy, he loved it. He loved people who weren’t going to take any shit from him.

Do you have a favorite memory of your time with Guy that you return to?

The first thing I think about is sitting at Guy’s kitchen table with him. I would go to Guy’s house for an official interview, and we would sit at his workbench and talk for a couple hours. But then I’d go the next day without my recorder and sit at the kitchen table and just talk, and he would go so much deeper into stories when there wasn’t any recording. So then I’d go back to my car and furiously write everything down that he had just said. During the last few months of his life I saw him nearly every day, and I loved sitting there with Guy and talking. That’s my comfort memory.

Another memory I think about is when I went on the road with Guy and Verlon for part of my research. Guy ate so much junk food. He ate more junk food than any one person I’ve ever seen, at every truck stop, at every McDonald’s. I sent Verlon a message, saying, “Does he always do this?” And Verlon said, “No, he’s holding back because you’re here.”

Enjoy this interview? Subscribe to the Oxford American.