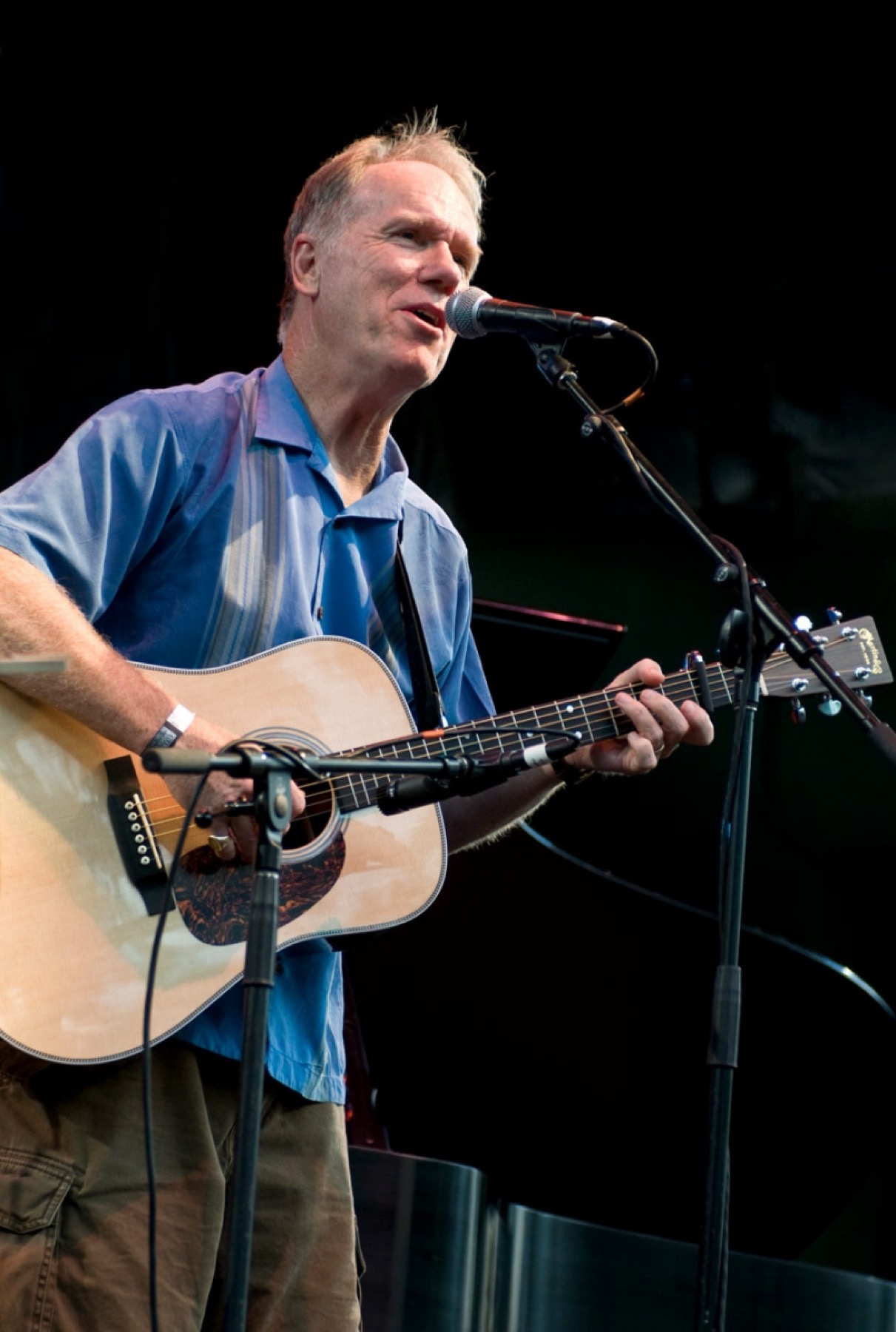

Loudon Wainwright © Ebet Roberts

LINER NOTES: A MEMOIR

By Loudon Wainwright III

From Liner Notes: A Memoir

An excerpt from Loudon Wainwright III’s Liner Notes: On Parents & Children, Exes & Excess, Death & Decay, & a Few of My Other Favorite Things, available now from Blue Rider Press. Reprinted by permission of Darhansoff & Verrill Literary Agents.

Nashville

This morning my old college buddy George Gerdes sent me another of his obit emails. I often get the news that yet another show biz luminary has passed, kicked, shuffled, etc. from the Double G. He’s had his antennae up for the final rite of passage for quite awhile. Double G made two albums in the 1970s. The first was called Obituary. That was followed by Son Of Obituary. This morning’s note from George was short and sort of sweet. Referencing my fourth record, Attempted Mustache, he wrote, “I am starting to grow a mustache in honor of the man who precedes us into the Great Unknown.” The record producer Bob Johnston had died at the age of eighty-three, ten days after Billy Sherrill bought the farm at seventy-eight. Two of Nashville’s greatest, down for the count in a single fortnight. Billy produced and wrote for George Jones and Tammy Wynette. Bob produced records with Dylan, Cohen, Cash, and even did one with me.

In 1972, after Album III and the strange, confusing success of “Dead Skunk,” I wasn’t sure what to do. I was now pegged as “the Skunk guy” and was feeling like I’d sold out. My first two Atlantic LPs had been voice and guitar affairs, critically successful but commercial duds. After being dropped by Atlantic, I was signed by Columbia. The powers that be (Clive Davis) decided that I had to stop goofing around and make a record that actually got played on the radio, so I was paired up with the producer Thomas Jefferson Kaye and a band called White Cloud. It worked. “Dead Skunk” got airplay and Album III got to about #35 on the Billboard album chart. But, always ready to indulge in self-loathing, I now felt guilty, ashamed of a commercial success, so when Bob Johnston came calling, in 1973, I got excited. This was the guy who’d produced Blonde On Blonde and John Wesley Harding. How could I not go there? There was Nashville.

Just a few weeks after Rufus was born in July of 1973, Kate and I set up camp with our newborn at Roger Miller’s King Of The Road Motel in Music City. That’s where we stayed while I made Attempted Mustache. There was a very talented blind singer-songwriter pianist working in the motel lounge bar every night named Ronnie Milsap. As long as I’m name dropping, my album was recorded at Ray Stevens’s Sound Laboratory. That’s Ray Stevens of “Ahab The Arab” fame.

I don’t know if they still make records quickly in Nashville, but Attempted Mustache was recorded in four days and mixed in two. We were out of there in less than a week. The players were some of the legendary cats of that time—Kenny Buttrey on drums and Tommy Cogbill on bass are both now dead. There were a clutch of great guitar players—Johnny Cristopher, Mac Gayden, Ron Cornelius, and Reggie Young. The piano player was Hargus “Pig” Robbins, who also happens to be blind. The late Doug Kershaw plays fiddle and yelps on “The Swimming Song.” Kate and I play banjos on that one, and she duets with me on “Dilated To Meet You,” a song written for Rufus when he was in utero, waiting in the wings, so to speak. Bob Johnston plied us with lots of red wine, as I recall. Rufus cried a lot in the motel at night, and we didn’t get a lot of sleep.

The record was a flop. Radio stations wanted to know why there wasn’t a funny animal song. The reviews were mixed, though Robert Christgau, of The Village Voice, gave it an A minus. In my opinion a number of my best songs are on it, including “Down Drinkin’ At The Bar,” “Lullabye,” “The Man That Couldn’t Cry,” and the aforementioned “Swimming Song.” A lot of people I played the record for, including my parents and my manager Milt Kramer, felt Attempted Mustache was over-produced and mixed badly. “It’s hard to hear the lyrics,” my father complained, and looking back, I think that’s a fair criticism. Still, the album has a loose, ramshackle feel to it, and some people like it a lot, including my daughter Martha, who has discerning taste. The photo on the front cover is pretty cool. We were driving around Nashville with the photographer Marshall Fallwell looking for a location to shoot in, when suddenly we drove past a funeral home—and there on the front lawn were a pair of plaster polar bears, each one holding an armful of plaster snowballs. I kicked off my shoes and posed next to one of them, flashing a stupid grin underneath the half-assed mustache I was attempting to raise at that time.

We’re wondering when you will arrive

We’re wondering what you’ll be

We’re wondering if you’ll be a her

Or if you’ll be a he

Maybe you’ll arrive today

Perhaps tomorrow night

We’re hoping you won’t hurt too much

And that you’ll be alright

Life has a few unpleasantries

We may as well confess

We suppose you’ll cry a lot

And that you’ll be a mess

Even though there’s trouble

Even though there’s fuss

We really think you’ll like it here

We hope that you like us

—“Dilated to Meet You,” 1973

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.