LISTENING IN

By Will Stephenson

On November 4, 2008, the night Barack Obama was elected president, Greil Marcus, the first-generation rock critic, wasn’t watching the victory speech in Grant Park with the rest of the country; he was in Minneapolis at a Bob Dylan concert. As an accident of scheduling, it’s an almost too-perfect juxtaposition for a writer forever drawn to the buried political inscriptions in pop music, to the notion of a "vast historical drama emerging out of a small private drama,” as he once described a Peter Handke novel. He must have recognized this, because he later wrote about that night for GQ: “The country may not have changed,” he said of the election, "but its history did. It rewrote itself."

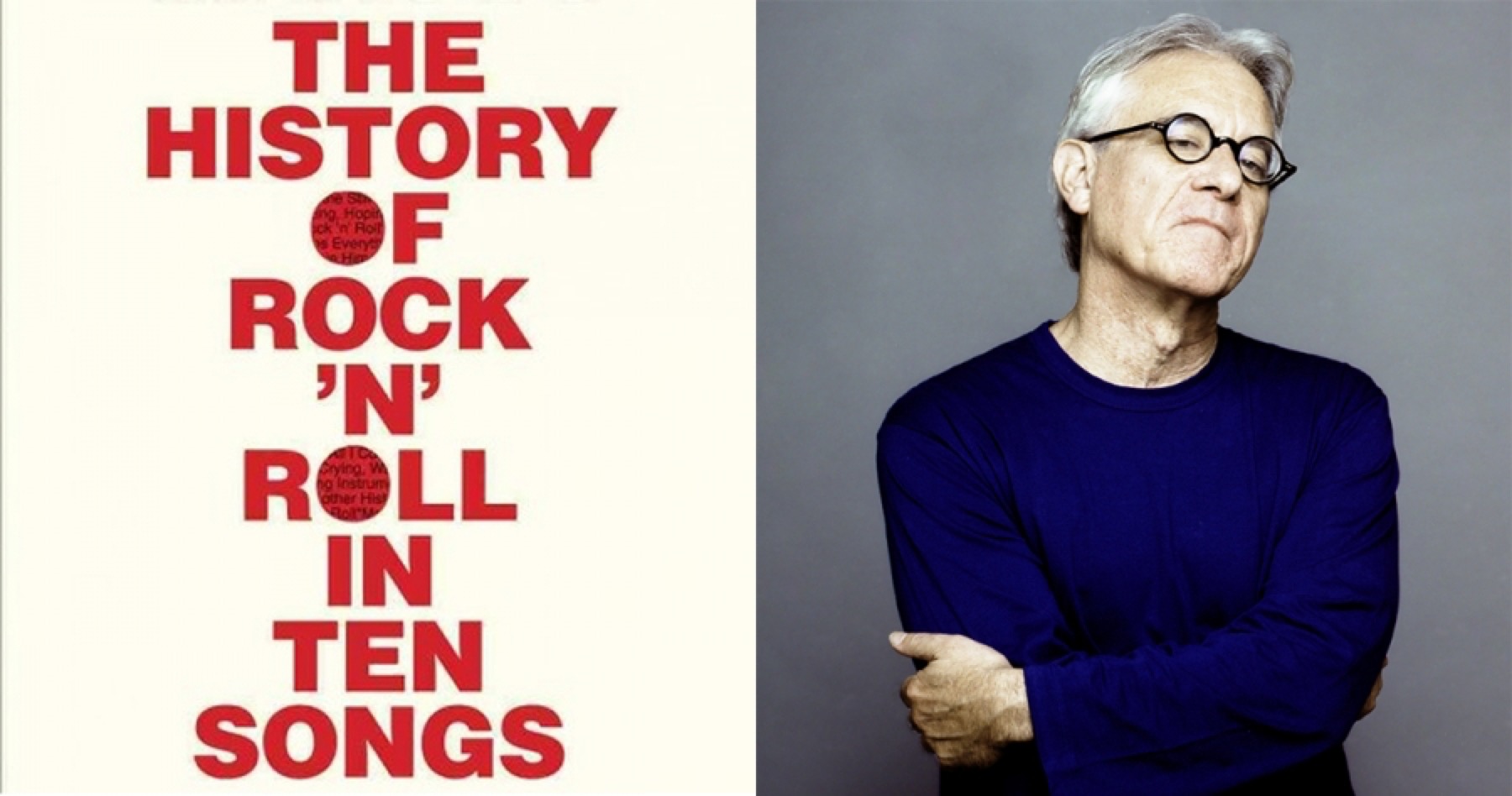

In an interview last year with the music journalist Simon Reynolds, as a half-baked, probably facetious aside, Marcus defined each of his major books by their corresponding presidential terms. His first, Mystery Train, he said, was “my Nixon book,” while Lipstick Traces, his study of the intellectual roots of punk rock, was his “Reagan book,” Invisible Republic (reprinted as The Old, Weird America) was his “Clinton book,” and The Shape of Things to Come, his 2007 essay collection, was his “Bush book.” It’s tempting, then, if maybe reckless—not that this would ever stop Marcus—to consider his latest, The History of Rock 'n' Roll in Ten Songs, in these terms. Obama, both as a public figure and as an icon of a putative era, is a constant presence here, a kind of ground note. There is the chapter on Beyoncé, which centers on his second inauguration, and the riff on Robert Johnson, which opens on blues night at the White House in 2012, with the president singing the chorus of Johnson's “Sweet Home Chicago.”

There is also that associated idea of history having rewritten itself, which is more or less this book’s animating impulse. As Marcus explains in his introduction, Ten Songs is an attempt to offer “a different story from the one any conventional, chronological, heroic history of rock 'n' roll seems to tell.” More accurately, it’s not a story at all, but, like an expanded version of one of his “Real Life Rock Top Ten” columns for The Believer, a group of idiosyncratic essays which use pop songs as jumping-off points for weird, prismatic webs of cultural observations. The songs, which range from Barrett Strong's 1960 single “Money (That's What I Want)” to the Flamin’ Groovies’ 1976 “Shake Some Action,” do not seem arbitrary, but they also do not seem especially important: They are occasions for his ideas about how music works on the public imagination.

Marcus has his prejudices in this respect; he views songs as documents of physical effort rather than as abstract, sonic experiences. He’s never shown any real interest in the recording studio as an instrument, in aura, artifice, or pure sound, which might explain his lack of serious engagement over the years with genres like hip-hop and dance—production for its own sake is of no use to his critical approach, which is built on public action. Even when he writes about Phil Spector, as he does here in one of the later chapters, he leans on the early, pre-“Wall of Sound” years (back when Spector still played instruments). The question guiding much of Marcus’s work, as he put it in the interview with Reynolds, is “How must the person who is making this music have felt at that moment?” And for this he needs to hear, or even better to see the human activity behind the record, so he often prefers to focus on real or imagined live performances—even the performances of actors in biopics like Cadillac Records or the Ian Curtis portrait Control.

Overall, though, the book is surprisingly inclusive for a brief, non-history of rock ‘n’ roll, a term which for Marcus encompasses soul, country, Christian Marclay installations, and contemporary R&B. Beyond the songs themselves, there is also his characteristically wide-ranging set of cultural reference points: Graham Greene, David Cronenberg, Colson Whitehead, Thomas Jefferson. Marcus, who like Tom Wolfe is a product of the mid-century emergence of American Studies departments, has always been a voracious and ambitiously interdisciplinary critic, and some of his more far-reaching analogies will seem either inspired or impractical depending on the reader. Like the subjects of the film Room 237, a documentary about eccentric interpretations of The Shining, no piece of evidence is too minor for Marcus, no historical event too distant. Beyoncé reminds him of Mitt Romney because she does; just as Elvis reminds him (in Mystery Train) of Herman Melville and the Sex Pistols remind him (in Lipstick Traces) of the British science-fiction film Quatermass and the Pit.

Over the years, Marcus has only gotten better at answering his own question—how must the musician have felt at that moment?—and more assured at describing the experience of listening. His prose, steeped in the disparate languages of academia, prophecy, and record reviews, has always been the fun part, and a few of the essays here mark some of his most vivid, brilliant work in years. His piece on Marclay’s Guitar Drag is a historical puzzle, pulling together a set of works in different mediums alongside musings on violence, noise, and history so that they all seem to belong together cleanly and absolutely.

Even stronger is the book’s centerpiece, a lengthy meditation on Buddy Holly’s “Crying, Waiting, Hoping” (particularly surprising to me because my interest in the life and music of Buddy Holly is essentially nonexistent). Marcus doesn’t so much ignore the kitschy legacy as see past it: “Holly looked for space in the noise,” he writes. “He built his music around silences, pauses, a catch in the throat, a wink.” He also makes a series of unexpected and powerful maneuvers, for instance triangulating the fact of Holly's death, making it physical and unsettling again, with stories like that of the woman he once met who, as a twelve-year-old, witnessed the site of the plane crash while the bodies were still being carried away on stretchers. The essay eventually intersects with the careers of Carole King, The Beatles during the Let It Be sessions, and the real women who inspired Holly and Ritchie Valens's most famous songs (Holly's “Peggy Sue” was Peggy Sue Rackham, later the “co-owner of the Sacramento sewer and drainage repair company Rapid Rooter”)

To Marcus, the famous and the obscure are as functionally indistinguishable as the high and low-brow. Motown leads him to The Brains leads him to Cyndi Lauper: all of it speaks, and deserves a response. The book it reminds me of most is Geoffrey O’Brien’s The Phantom Empire: Movies in the Mind of the 20th Century; both read like the dream journals of life-long obsessives, conspiracy theories constructed out of pop fragments. Marcus’s great innovation this time is realizing that, when charting the history of something like rock ‘n’ roll, it doesn’t really matter where you start, or which direction you go in. He allows himself to become, as he has written of Gilbert Seldes, a “time-traveling journalist listening in as a century spilled its secrets.” And at this point, there’s no better listener.