More Back Story

An excerpt from Word for Word

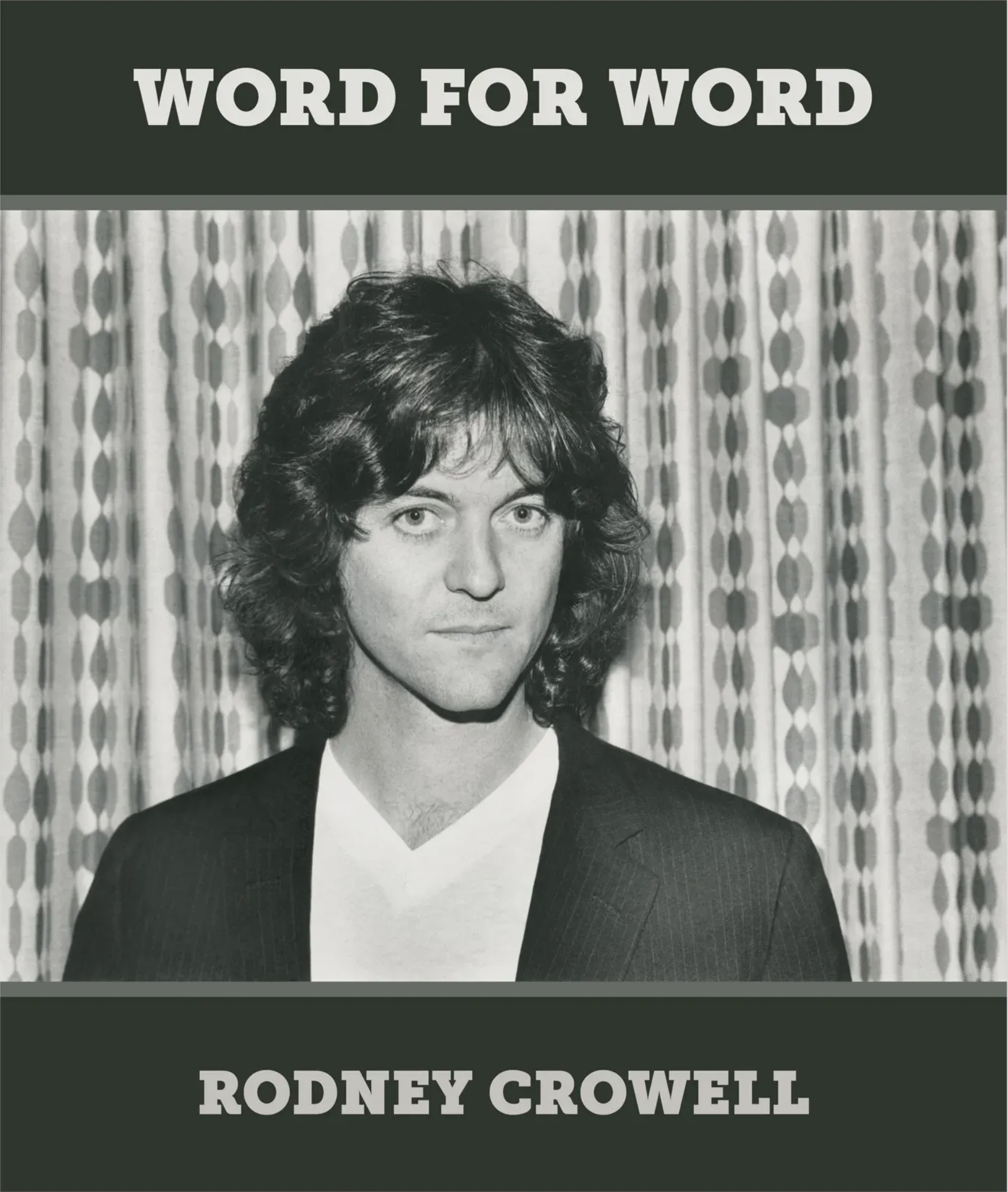

By Rodney Crowell

Word for Word is available now from BMG Books

This exclusive feature is a part of the OA's Country Roots: Web Edition, an online extension of our annual music issue. Pre-order the Country Roots Music Issue and companion CD here.

I left home at age fifteen to join a rock and roll band named The Arbitrators and five years later formed a folk duo called Rodney & Donivan with my college roommate. His older brother, Walter Martin Cowart, was a pot-smoking, Bob Dylan-quoting poet, songwriter, and long-haul trucker and instant role-model. His tales of the open road made the prospect of a degree in cultural anthropology, with a minor in political science even less appealing than assembling chicken coops for the Bright Coop Company, which is one of the ways Donivan and I managed to pay for the right to flunk out of Stephen F. Austin University. The other was playing cover songs in a half-empty Holiday Inn lounge.

In the spring of 1972, Rodney & Donivan got discovered by an alcoholic record producer from Pasadena, Texas, one of the incorporated cities contributing to Houston’s greater sprawl. In early August, I received a collect call from the long-silent producer with orders to round up Donivan and head for Nashville where a ten-year recording contract with Columbia Records and the opening slot on a year-long Kenny Rogers and the First Edition concert tour awaited our arrival. Around 3:00 a.m. on the morning after my twenty-second birthday, we rolled into Music City USA. The next three weeks were spent knocking on, and being turned away from, practically every door on Music Row. Nobody had ever heard of Rodney & Donivan. Meanwhile, no less than twenty of our collect calls to Pasadena went unanswered. Eventually, a songwriting friend of the producer’s decided to drive up from Houston and fill in the blanks on what had become of our skyrocketing recording career. In a meeting that lasted no more than fifteen minutes, the amphetamine-wired associate explained our ever-sozzled producer, for the price of a bus ticket home, had sold our eight-track, master tapes and song-publishing rights to a company called Sure-Fire Music. The next day, Donivan and I cased out the company’s building, and the day after that, during lunchtime, while he distracted the lonesome receptionist with small talk, I slipped the tapes and papers under my jacket, then we strolled out the door. This stolen property’s still in my possession.

After the heist, the duo broke up when Donivan and the young wife he’d left waiting (semi-patiently) back in Texas decided to give Arizona a try. I opted to stick it out in Nashville, which involved continuing to sleep in my car, or on top of picnic tables scattered through the city’s many parks. Thankfully, as the weather began turning cold, I ran into a pair of self-styled reprobates in the back room of Bishop’s Pub, the only venue in town where a street-level songwriter could sign up to play a twenty-minute set, pass the hat for tips, and, depending on how much beer he drank, walk away with a few bucks in his pocket. Luckily, the club owner’s girlfriend took an interest in my well-being, and every night I played, she’d spot me a hamburger and pitcher of beer. With that and the five dollars I usually found in my hat, I was getting by.

One evening I was looking for an empty booth where I could enjoy my free supper when I noticed a six-foot-seven, one-hundred-and-forty-pound humanoid leaning on a cue next to the pool table. As I passed by, he hocked up a giant loogie and spat it into my beer. “You won’t be needing any of this now, will ya?” Sneering, he grabbed the pitcher out of my hand and started glugging. I was surprised to hear myself say “I guess this means we’re gonna be friends,” and even more so when “Give me half of that hamburger and we’ll see,” was his response.

This, to my good fortune, turned out to be Dennis Sanchez, an out-of-work upright bass player from Long Beach, California, who Guy Clark had already immortalized as Skinny Dennis in the song “L.A. Freeway.” Skinny Dennis needed some help with the rent on a two-bedroom house that happened to be within walking distance of the pub and, as luck would have it, the restaurant where I’d just stumbled onto a job as a dishwasher.

Overnight, that house on Acklen Avenue became a magnet for all the alternative-country, Texas blues, folk-rock and mainstream country singer/songwriters who, thanks to Kris Kristofferson’s mega-success, were pouring into Nashville in the early seventies. That’s where I met Guy and Susanna Clark, Townes Van Zandt, Mickey Newbury, Rocky Hill, Jim Maguire, David Allan Coe, Rex Bell, Harlan White, John Lomax III, David Olney, Mickey White, Steve Young, Johnny Rodriguez, Dave Loggins, Robin and Linda Williams, and Mayo Thompson. More often than not, after getting off work around two in the morning, I’d walk home and find the house full of stoned songwriters hell-bent on one-upping one another with whichever song they’d just written and could barely remember the words to. A rare perk of late-shift dishwashing was the opportunity to finish off all the leftover half-empty cocktails, so most nights I stumbled home in the same shape as our drunken houseguests.

My first contribution to these get-togethers was a song my father taught me, “You Gotta Have a License.” From then on, I was known as the guy who knew the words to more old songs than anybody else. Which might be why Guy Clark and I became fast friends.

Guy was the curator of this Acklen Avenue song-swapping salon. When too many brand-new clunkers started grinding the party to a halt, Guy would call on me to play Chuck Berry’s “Nadine,” or an up-tempo sing-along like “My Home’s Across the Blue Ridge Mountains” to get things moving again. As daybreak approached, it might be an Appalachian dead-baby song I’d learned from my dad or, even better, the not-so-subtle “Show Me the Way to Go Home.” This knack allowed me to contribute without exposing how vapid my own compositions were at that time. Even more important was the chance to witness great songwriting up close. I was sitting two feet away from Townes Van Zandt the first time I ever heard “Poncho and Lefty.” Same goes for Dave Loggins’s “Please Come To Boston.”

Our growing friendship began having a lasting effect on my abilities as a songwriter. Guy was fond of making the point that for any dedicated writer—poet, novelist, songwriter, or journalist—getting better at what they do is the only measure of success. He put it to me like this: “Look, you can be a star, or you can be an artist. If rich and famous is what you’re looking for, go on and knock yourself out. Just know that staying rich and famous will eventually involve putting your personality ahead of your art. If you pay attention only to the quality and integrity of the work, the money will eventually come. Probably just not as much as if you were a star.”

Now and then, he’d play his prized recordings of Dylan Thomas reading A Child’s Christmas in Wales and Under Milk Wood and reiterate his belief that the words to a well-written song should sound as good read aloud as they do when sung. As time went on, and I started writing slightly better songs, if I thought I’d written something worthwhile, I would head over to Guy’s house and—looking him square in the eye—recite the lyrics. Any impulse to turn away from his all-knowing gaze was the tell-tale sign that a line or couplet didn’t make the cut. Occasionally, he’d drop by my place and do the same. This went on until the last few months of his life.

Susanna’s influence was more intuitive. While Guy and I often tried to bring the practicalities of songwriting—self-editing, narrative structure, and integrity—into focus, with Susanna it was all about the emotional experience. She was interested only in how a song made her feel. More or less by osmosis, I adopted her credo that a song should never draw attention to the mechanics involved in its creation. “I don’t care how it’s done, I only care what it does,” is how she put it. As eager as I was to read new lyrics to Guy, I was even more keen to sing them to Susanna. Without her approval, a song simply wasn’t a song.

By the winter of ‘73, I was holed up in a Hillsboro Village duplex with a new girlfriend and my beloved dog, Banjo. Meanwhile, Skinny Dennis had hot-wired the one-room efficiency behind our apartment and was squatting there, Ratso Rizzo style, with his bass, a hot plate, and one change of clothes. The four of us (Banjo included) passed many bitter-cold evenings huddled around a pathetic little heater, eating brown rice and beans, and watching crappy black-and-white TV when we weren’t listening to records. In those short gray days, I wrote “Bluebird Wine,” “Song For The Life,” and “An American Dream.”

In early spring, a Nova Scotian bass player, Skip Beckwith, breezed into town hoping to convince a friend of mine to join him in Anne Murray’s touring band. For reasons long since forgotten, their meeting took place in our apartment. After making a deal with his guitarist, the band leader then turned to me and asked if I had any new songs he could hear. Caught off-guard, I managed to play somewhat decent versions of the three I’d just written and, much to my surprise, he said he’d deliver a demo tape to his boss up in Toronto.

The songs never reached Anne Murray. Her producer, Brian Ahern, was also working on Emmylou Harris’s debut album. As she later told me, they’d wasted several days playing demo tapes without hearing a single song she could imagine recording. As a last resort, Ahern pulled out a reel-to-reel demo a bass-playing friend had given him a couple of months before. The first song on this tape was “Bluebird Wine,” which wound up being the opening track on Emmylou’s Pieces of the Sky.

For much of the late summer and fall of ‘74, I was in Toronto. Then, in January, Emmylou called to say she and the Angel Band would be playing at the Armadillo World Headquarters in a few days and that she was hoping I’d sing a couple of songs with her. After the show, she casually mentioned that she was flying out to Los Angeles the next morning and thought, since she just happened to have a spare ticket, it would be great if I wanted to come along.

Meanwhile, Skinny Dennis had returned to Southern California and was backing up a folksinger named John Penn. I’d been in L.A. only a month or two when I heard he’d collapsed onstage at a Long Beach folk club and was dead before he hit the floor. Would I mind being a pallbearer, the caller asked.

At the funeral, I learned from a family member that the cause of my friend’s physical abnormalities, and perhaps even his heart-attack, was a genetically-inherited disease known as the Marfan Syndrome, which affects the cardiovascular system and skeletal structure of its victims. I also learned that Dennis’s family members were descendants of an Indian tribe in northern Mexico whose adult males averaged five-feet-four-inches in height. This explained why I was a full head taller than most people there, and also clarified something Dennis often said that I’d never fully understood: “I’m as long on lonesome and ugly as my people are short on tall.”

After I said goodbye to my old bass playing friend, I hit the road as a member of Emmylou Harris’s Hot Band.

Used with permission from BMG Books, © 2022