Photo by Wyatt McSpadden

MUSICAL TRUTH AND BITTER BEAUTY

By Ronni Lundy

Lowdown from the High Country

Dreams are about the future

Songs about the past

Sometimes it takes a suture

To make a feeling last.

—“Sweeter than the Scars,” Shinyribs

Ihave never been keen on equipment. Back in the day when I reviewed pop music for a living, I depended on my spouse and an old friend at Circuit City to figure out how I’d play the deluge of albums. The sound surrounded and seemed just fine to me, but when a critic mentee/whippersnapper dropped by one afternoon, he was appalled to find me so far from state-of-the-art.

“Hey,” I said, with what I hoped was a lofty lift of the eyebrow, “I listen to music, not sound.”

That hardly explained a thing, but was cryptic enough to end the discussion. And maybe it opens to a zen koan-like corollary about lyrics now, since the ones I love the most are less about something tangible and direct than about the shadows they cast, off to the side.

All this is to slide sideways into saying that lately, in these days of Weltschmerz and my aging, I’ve been finding comfort and healing in riding the mountains with Shinyribs in the Chevy Astro’s old snap, crackle, popping CD player.

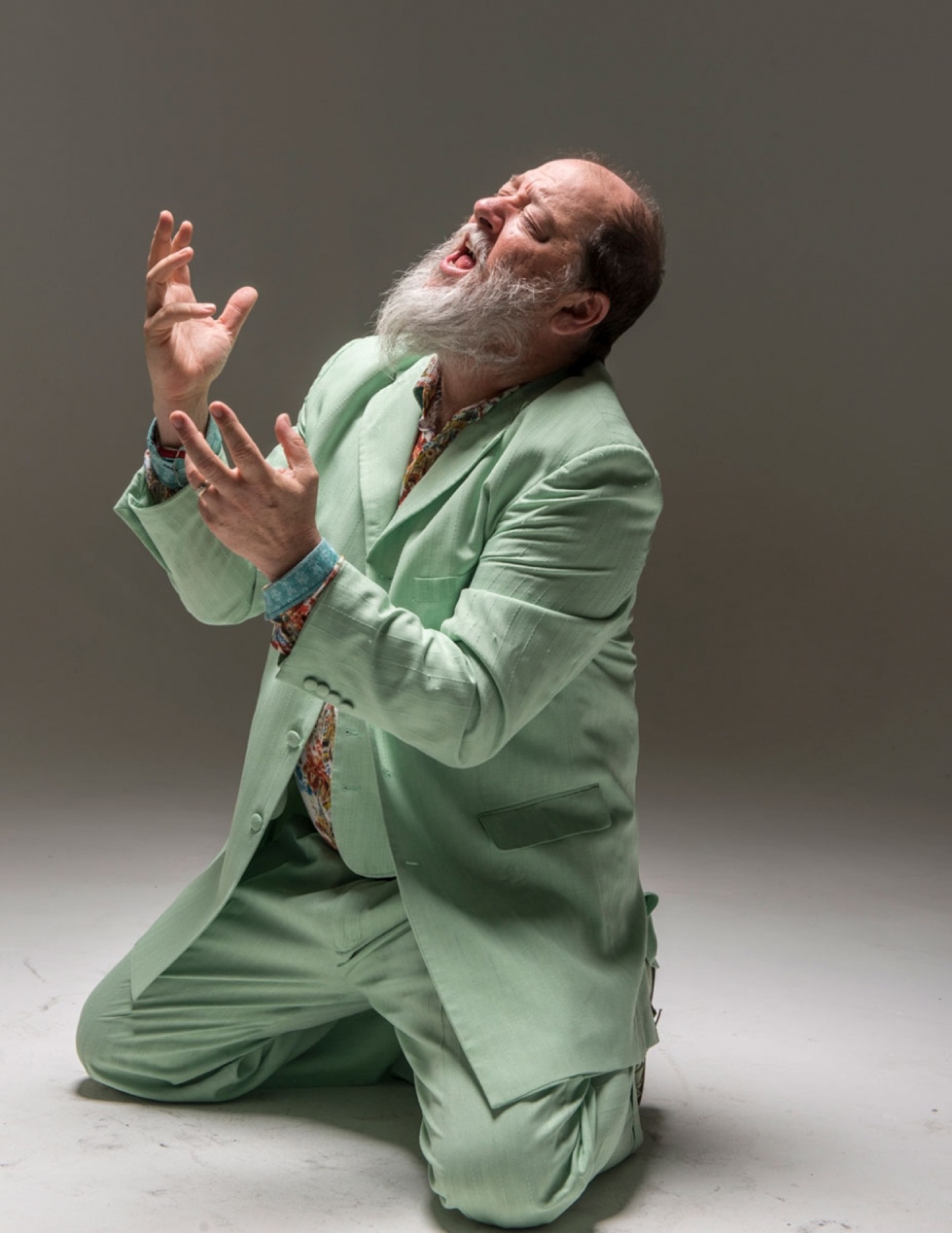

If you are unfamiliar with Texan Kevin Russell, the singer/songwriter and guitar, mandolin, and ukulele player who lately goes by the nom de pluck Shinyribs, as does his brilliant funking, picking, and punking band, it is totally misleading for me to introduce you, as I just did, as if he were a man of constant sorrow. In fact, Russell—clad in his pistachio green, or orange plaid, or lip-blotting pink/red booty-shaking suit, and backed by a core of ticking, riffing sidemen, the Tijuana Trainwreck Horns, and the Shiny Soul Sisters—leads one of the finest party bands around and, when called for, a heckuva crowd rousing conga line.

When I’m riding with my grandson in car-seat shotgun, he requests “Donut Taco Palace,” and I crank this Farfisa glittering, Joe King Carrasco invoking ode to Austin fast food as loud as it will go and we both shout along. Someday “Bolshevik Sugarcane” or the ska-powered “Upsetter” will force me to pull over, hop out, and start dancing on the side of the highway. And the band’s sizzling live cover of “Golden Years” (check out the YouTube video from Music City Roots) makes me want to outfit the back of the Astro with a bunk and a burner, and spend my life following Shinyribs across their Texas homeland.

But even a tune like “Red Quasar,” with its Soul Train drive and exhilarating horn break, reveals a palimpsest that is ultimately, inevitably darker. I “met” Shinyribs when this song came crackling through the static on the Astro’s radio, courtesy of Spindale, North Carolina’s WNCW. Happily hooked by the music, I was utterly wowed by what lyrics I could catch. Magical metaphors for spinning: “Like a disco ball at a new gay bar / Like a beach ball baby in a livestock yard.” But as the plangent edge to those horns began to sink in, so did my awareness that the spin was a spiral descending just a bit darker with each turn: “Like a piston pinging in a breaking down car / Like gravity in a collapsing star.” Seeping in, “Quasar” became for me a bittersweet, irony-tinged, it’s-the-end-of-the-world-so-let’s-dance anthem.

So in the spring of last year, it was a no-brainer to make a trek to Knoxville for a trifecta of musical truth and bitter beauty: Darrell Scott opening for John Prine at the Tennessee Theater one night, Shinyribs on the tiny stage at Boyd’s Jig and Reel on another. By the time my immersion was over, I felt as if I’d been baptized at an old-time revival—one full of gospel shouts at Armageddon. Each of these brilliant songwriters is a master at revealing the depths of both despair and redemption lying just below the quotidian. Prine crafts short stories set to simple unforgettable melodies. Scott is a heart stopping poet weaving magic with words and meter. Russell, as Shinyribs, flings glittering carnival beads strung with haiku.

“Little boy gnawing / on a cinnamon roll / he loves his mama so / and he’s five years old / tomorrow.”

—“Limpia Hotel [Chihuahua Desert].”

“It’s like lighting yourself on fire / in your own home.”

—“Feels Like Rain.”

And back again to “Sweeter Than the Scars”: “A story lost in time / folded in mold and mildew / tied in dry rot and twine.”

In fact, the entirety of “Dead Batteries” is simply one poignant slash mark laid after another marking a path to acceptance and compassion. “Lately I’ve been going home / on bridges over low water slow.”

Russell’s gift for juxtaposition in lieu of exposition allows a song to become as deeply layered as a memorable dream. In his capable hands, “Pack-It-Rite” becomes a paean to the corner store, a quick slap at “that same old bourgeois bullshit / always killing the spark,” and a sweet moment of reverie for carelessly lost love. “Take Me Lake Charles” lays out the irresistible allure of both addiction and the silver-tongued addict clearer than a year of codependent meetings will, while “Walt Disney” delivers the tough love both need with a cleverly lethal cleaver.

And somehow “Song of Lime Juice and Despair,” the yodeling ode that inspired the descriptors Crisco Music (country disco) and Salvador Dolly Parton-esque, dances its way straight into the realm of an epic somewhere between Marty Robbins’s “El Paso” and Townes’s “Pancho and Lefty.”

But enough. I’ve never been as keen on talking about music as driving or dancing to it. So click on over to whatever place you can to get a taste of Shinyribs. You can thank me later.

“Lowdown from the High Country” is a part of our weekly story series, The By and By.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.