ON THE PLATE

By Dean Young

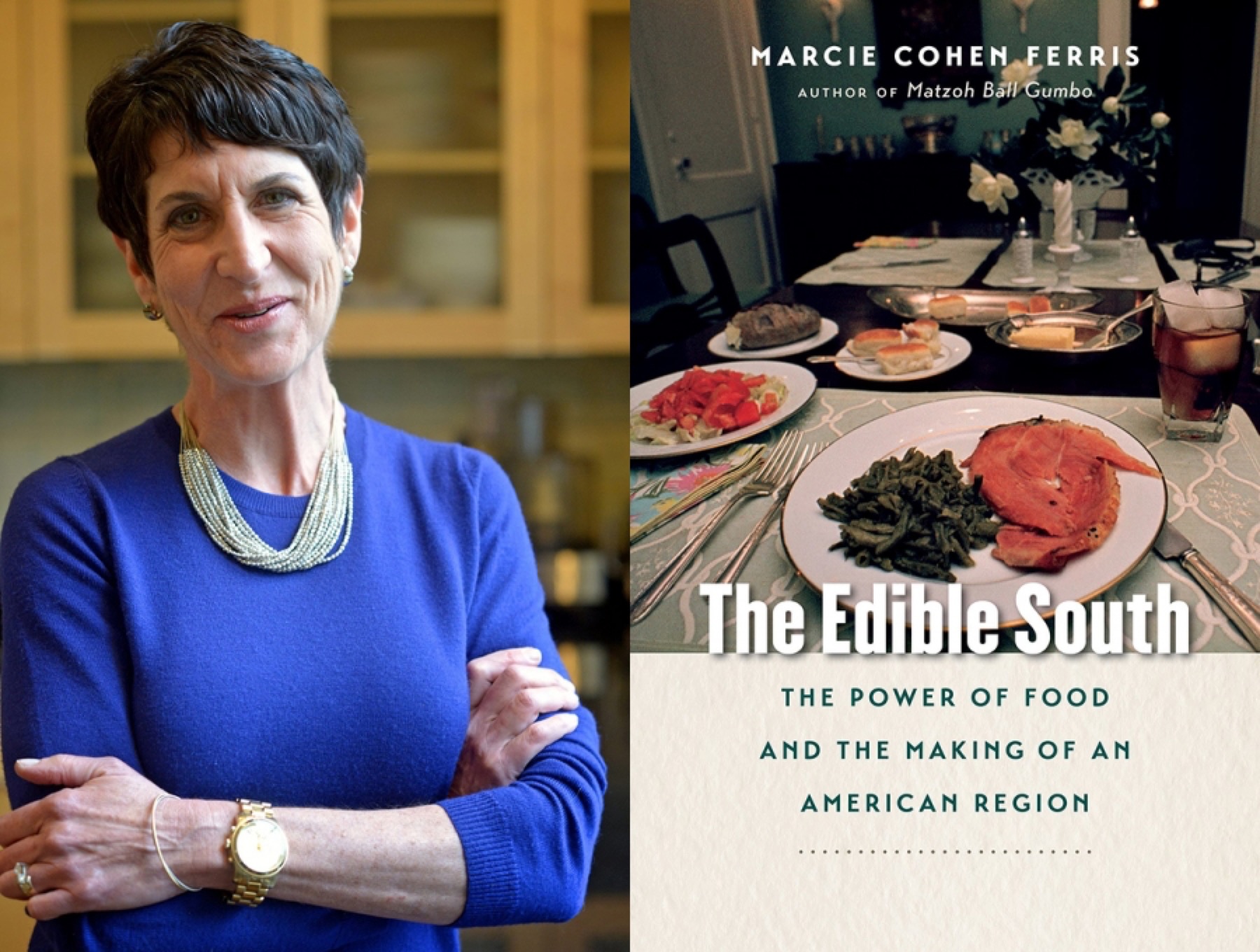

The South is a place of contradiction. The picturesque, pastoral scenes of a bountiful Dixie harshly juxtapose against the grotesque, historical realities of the region: slavery, racism, sexism, and exploitation. And according to UNC professor and author Marcie Cohen Ferris, nowhere is this notion more acute than at the Southern table. In her new book, The Edible South: The Power of Food and the Making of an American Region, she asks readers to look past the delectable, traditional fare that garnishes their plates to better understand greater truths about the fascinating but often disturbing history of Southern foodways. Not only does Ferris pinpoint and chronicle evocative moments throughout the South’s larger history, but she manages to eloquently express how this history shaped Southern cuisine and, to a greater extent, Southern identity.

I met up with Ferris in October while she was in Nashville for the Southern Festival of Books.

What led you to embark on such an ambitious project?

It’s been about a seven-year ordeal, though I think I’ve been steeped in this for about fifty-seven years, or however old I am; these are the waters that I’ve swum in for a long time. Food is really my way of understanding the Southern worlds that I live in.

I also felt that there was a need for a text that looked at a long arc of the American South, but was not an extensive culinary history. My work is more of a conversation about what I saw as watershed moments in Southern history that intersected with Southern food.

You use the word “conversation” a lot in your book to discuss that idea, too.

Yes, I do. This book is really a collection of the voices who were speaking, talking, and engaged with fighting about their experience as Southerners. Food is the way that we understand their experience of race, of class, of power, of gender. For me, food is just another lens onto the American South, but it’s a particularly compelling one because everybody eats.

Southern history is about contradiction and contrast, and we see those same forces at play in Southern food. I really wanted to bring together the important moments of Southern history that help us understand why Southern food is the way it is. I wanted to be sure that I told at least some of that basic history, as well as shared a range of voices, both black and white, that were important tellers of these stories.

So, this is my curated view of the important stories that reflect the intersection of Southern history andSouthern food. How do we make Southern food less of the caricature and stereotype that it is in popular culture? Then, flipping that, how does Southern food help us to break apart and make sense ofthe complex world of Southern history? Do we hear different voices? Do we perhaps hear women’s voices a little more loudly? We certainly hear African-American voices more loudly throughout this work; they own much of this real estate intellectually and creatively. This was an opportunity to foreground their responsibility in these worlds.

You write about the South as a global place. Was it difficult for you to define the South anddiscuss what it means to identify as Southern?

That’s a great question. As long as the people that I was studying and trying to capture identified asSoutherners and saw the world they lived in as Southern, then it was Southern to me—that’s how I defined it.

You write that food is often overlooked in much of Southern history. Why do you think that is?

I think historians in another era might not have understood food as a powerful, expressive force, but it always has been. There was a sexist understanding of food’s connection to domestic spaces, to women, and to their disempowerment. After the social movements of the Sixties and Seventies, we know that that is absolutely not true. In fact, food is really one of the most powerful ways for us to understand social history.

Does this get back to the idea as the South as a place of contradiction, especially regarding food?

Yes. I think Southern food is everything that Southern history is: it’s creative, it’s abundant, it’s full, it’s delicious, it’s beautiful, it’s warm, it’s inviting, it’s hospitable, and it brings family together. But when you flip it, as you do Southern history, you find a dark side of impoverishment, malnutrition, denied access to food, land loss, food-related disease throughout Southern history and even in the contemporary South. It’s complex, but food is history, power, place. I just hope that I can convey that it’s a complex, dynamic, multi-layered story.

Why is your book relevant right now?

It’s really important to have this book out today because there’s never been a time of more popularity regarding the presence and availability of food in American culture. There’s incredible work that’s happening in local food economies in the South and in restaurants and in small-scale farming. That work is best respected by studying the history that lies behind it.

In many cases, Southern food as a world becomes flattened—it becomes lampooned and cartoonish. Visitors want to taste a mythic South. I hope that that non-Southerners will begin to understand that there is a much more complex narrative—that this isn’t a world of plantation caricatures but a muchmore diverse collection of regions, each with its own distinct culinary culture.

What surprised you the most while you were writing this book?

The consistency of the three Ms: meal, meat, and molasses. Cornmeal, pork, and molasses are still at the heart of the Southern culinary grammar, from the early South to today’s vibrant reinterpretations of these core foods by farm-to-table chefs.

You know, there’s food everywhere—there are powerful food voices in every imaginable archival source. One just has to look for those voices, and youbegin to find food as a language in people’s conversation: in their letters and diaries, you very much begin to see this ethnographic experience.

I talk about young white governesses who come to the South to work for large plantations. They become ethnographers of sorts as they try to understand this beast that is the South. They are trying to understand this very strange world of race and class and gender that is so foreign to them, and they learn much of the racial etiquette at mealtime. Food is a powerful language to understand societal forces. It isn’t that we haven’t recognized some of the important women diarists before, but we just didn’t hear them speaking about how food empowered or disempowered them.

This project is more than recipes and cooking; it’s really about understanding how food helps us to better comprehend the Southern experience.

What does food mean to you?

For me, food reflects patterns of power, love, family, loss. Large issues that the South has grappled with for centuries: it’s all there on the plate. My favorite Southern food is a plate of field peas, collard greens, cornbread, and a piece of catfish. I don’t like it all fancy-fied; I just want it straight up with a little hot sauce. But today I also understand that this plate is weighty, and that it carries a deep history.

Food is a complex touchstone, and it’s so personal. After writing this book and my other book, Matzoh Ball Gumbo: Culinary Tales of the Jewish South,food became about my Jewish identity and the places where being Jewish and being Southern was distant. This book clearly helped me understand that food has been a place of great joy and great sadness. But, you know: that’s Southern history.