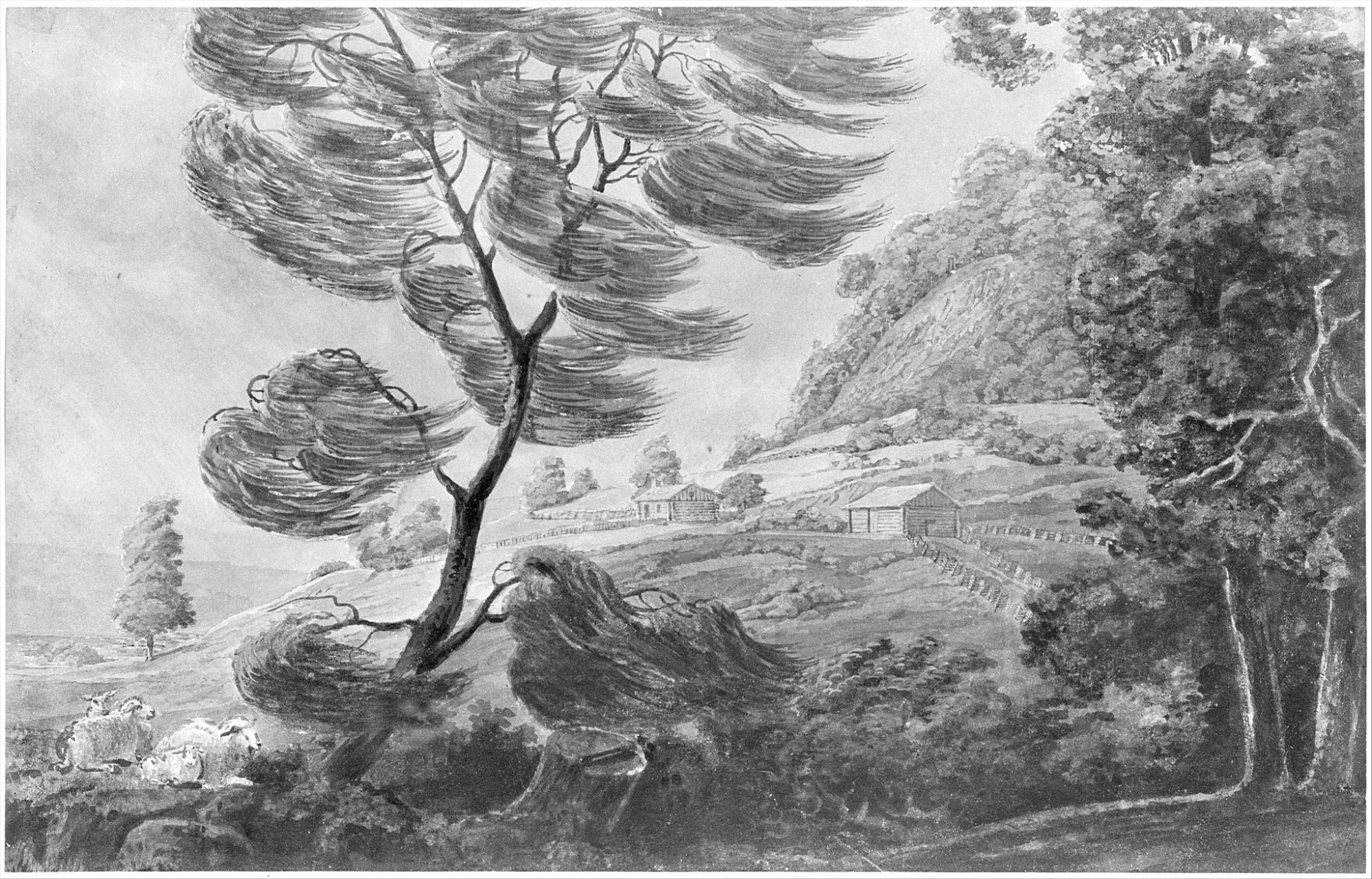

"The Tornado," 1811-ca.1813. Watercolor and graphite on white wove paper, by Pavel Petrovich Svinin. Courtesy the MET and Rogers Fund, 1942

Other Kinds of Power

By Allyn West

They drove as far as they could, Nanc Gunn told me, and then she and her husband got out of their truck to walk around the trees and utility poles blocking the way.

It was Saturday morning, December 11, 2021. The night before, after my 6-year-old daughter had fallen asleep at her mother’s house about 25 miles away in Murray, the tornadoes that had blown across four states for hundreds of miles arrived in Mayfield, Kentucky. More than a hundred people were working late at a candle factory to fill seasonal orders when, around 9:30 P.M., the roof blew off, and people were trapped under collapsed walls while the air filled with the scents of lavender and vanilla.

Gunn told me the tornadoes stayed in Mayfield only forty-five seconds—long enough, somehow, to kill nine people and decimate the town’s historic core—the 1889 courthouse, the post office, the police and fire departments, a hotel, the American Legion building, a church, just about every goddamn tree. The courthouse’s ornate clock tower was toppled and lay scattered around the obelisk of a Confederate monument relocated from Georgia more than a hundred years ago.

We woke up without power. The group text I’m in with the parents of my daughter’s closest friends in Murray started pinging: Everyone OK? Anyone need anything? One mother said she’d heard it could be weeks until our power came back.

In Mayfield, a town of about 10,000, Gunn and her husband had driven in toward the art guild where she’s the director. Located in a former ice house near the courthouse downtown, it had a small gallery, a shop, a space for classes and events. The other side of the building was a kind of museum filled with rusted plows and other tools of rural life. For years, this building was where people came for blocks to make ice cream at home. “The gallery,” Gunn told me, “was full of beautiful things.”

But many of them, she’d find that morning, were lost—eventually, after she and her husband filled their truck with the things she could save, she’d file insurance claims for 109 artists.

In her office, Gunn had hung a painting by Helen LaFrance. A Mayfield native, LaFrance, who was Black, grew up during Jim Crow. She taught herself to paint and produced hundreds of works before she passed at 101 in a nursing home just a few miles away. When Gunn found her painting, which depicted a house, surrounded by “yellowish wheat fields” and a perfectly “teal” sky, she saw it had been torn in three places.

I’d seen LaFrance’s paintings before. During the pandemic, I relocated from Houston to Murray, where my daughter had been living with her mother since 2017. Every other weekend, when I didn’t have her, I tried to get out to see as much as I could of western Kentucky, the part of the state the rest of the state tends to forget, I’ve heard. One of my first stops was the art guild. Driving there on 121, I was feeling embraced by the landscape, surrounded by rolling farmland with fence posts where hawks perch, passing house after house LaFrance could have painted by heart.

But it took me a while to go see the damage for myself. I didn’t want to be a tourist, but I’d come to believe it’s important to witness, to pay respects, as peculiar as mine are. Turning off the highway, I saw Mayfield as I’d always seen it. The newer chains at the edge of town—the Walmart, the Applebee’s, the Lowe’s—were as busy as they always were. A blown-out Sonic sign a mile in was the first real evidence of what happened. Soon, though, as I crested a hill into downtown, it was everywhere. So much of everything was nowhere to be seen.

I parked at the CVS, the cheap architecture spared, somehow, and started walking, listening to the low grumble of generators, excavators clunking heavily over uneven ground to take one more bite of debris. I saw, in a pile of tinder that used to be a house, someone’s kitchen sink. I saw a child’s formal dress lying in a parking lot, still on the hanger. A car missing every window. A strip of lace entwined with a power line. The blown-out wall of the theater inside the American Legion building, the seats now facing the rubble. The graffiti of search-and-rescue teams tagging houses cleared of bodies. A street lined with new utility poles, but no wires, not yet. Gunn told me her power came back after three days. “But in some areas,” she said, “there really weren’t any buildings to turn power on for.”

In Houston, I’d lived through chemical explosions, hurricanes, tropical storms, 100-year floods, 500-year floods. Apparently, I had brought all of them with me when I moved to Kentucky. All weekend, my body wouldn’t stop remembering, and I was angry, but at what? The wind? Maybe it’s the anger of powerlessness. There’s nothing anyone can do to stop any of it from happening again.

It’s September, now, nine months later. The damage is still here. The courthouse, a grim, gaping monument, was finally leveled last week. All winter, at Exit 43 on I-69, you could see scraps of a pole barn lying in a field, a towering steel light pole bent in half like a sunflower, a bottomland forest toppled, the dead trees lying caught on the branches of those that weren’t. Once, when we were driving to Paducah, my daughter sighed in her car seat and said, “It’s too sad to look.”

It’s been long enough, now, for our changing climate to create another disaster, flooding this time, on the eastern side of the state. Thirty-nine more people died just ahead of a new school year, and the number has grown. Governor Andy Beshear sent $21 million to Mayfield, and he signed a bill to send $200 million more to a region that includes Perry County, where 83 percent of the students are on free or reduced lunch.

Electricity comes back on, but small places like these lack other kinds of power. It’s almost as though they are their own back-up generators for a country that doesn’t run very well for the working class. Campaign promises of free community college, debt forgiveness, a higher minimum wage, and job training for the energy transition haven’t come true. The per capita income in Mayfield is nineteen thousand dollars a year. A third of residents live below the poverty line. Almost 65 percent of the people here rent, nearly 30 percent higher than the national average, because it’s hard to afford a house and support a family on the salary from Walmart, Lowe’s, or Applebee’s. I don’t know that anyone knows how to stop these slower disasters, either.

“Everything takes time,” Jason Lemle told me. He was hired to work for Graves County on economic development, but it’s become more about recovery. A Dallas native, he moved here with his wife from Bowling Green. Mayfield, he said, has a history of overcoming “terrible situations.”

In 2003, Ingersoll-Rand, which employed 400 people, abruptly left town. General Tire had been open for “50 or 60 years,” Lemle said, but laid off up to 1,500 people around the same time. But he’s heard stories of people who’d lost their jobs taking the expertise they’d earned to start their own small businesses. “The ability to overcome misfortunes,” he said, “has allowed Mayfield to be one of the most resilient places I've ever seen.”

A few weeks ago, my daughter and I were driving home past Exit 43, and the blown-over trees are getting harder to see for the new growth. Some, improbably, are still growing, if sideways. Lemle and his wife are expecting a baby. Gunn’s LaFrance painting was restored by an art expert in Paducah. “If you didn't know,” she said, “you would never know it had been through the tornado.”

There’s a kind of resilience that refuses to stop whether our structures fail or not. The last time I was in Mayfield, I watched a man in Carhartt overalls perched on a pile of bricks, maybe 10, 12 feet in the air. He was surrounded by billions of dollars of damage. I watched him for a minute, maybe two. Steadily, he was picking up bricks, then turning and tossing them behind him into another pile. I didn’t want to pry. This is his community. But if you didn’t know, you would never know what he was doing. It looked as though he were taking Mayfield apart and building it all over again all at once.