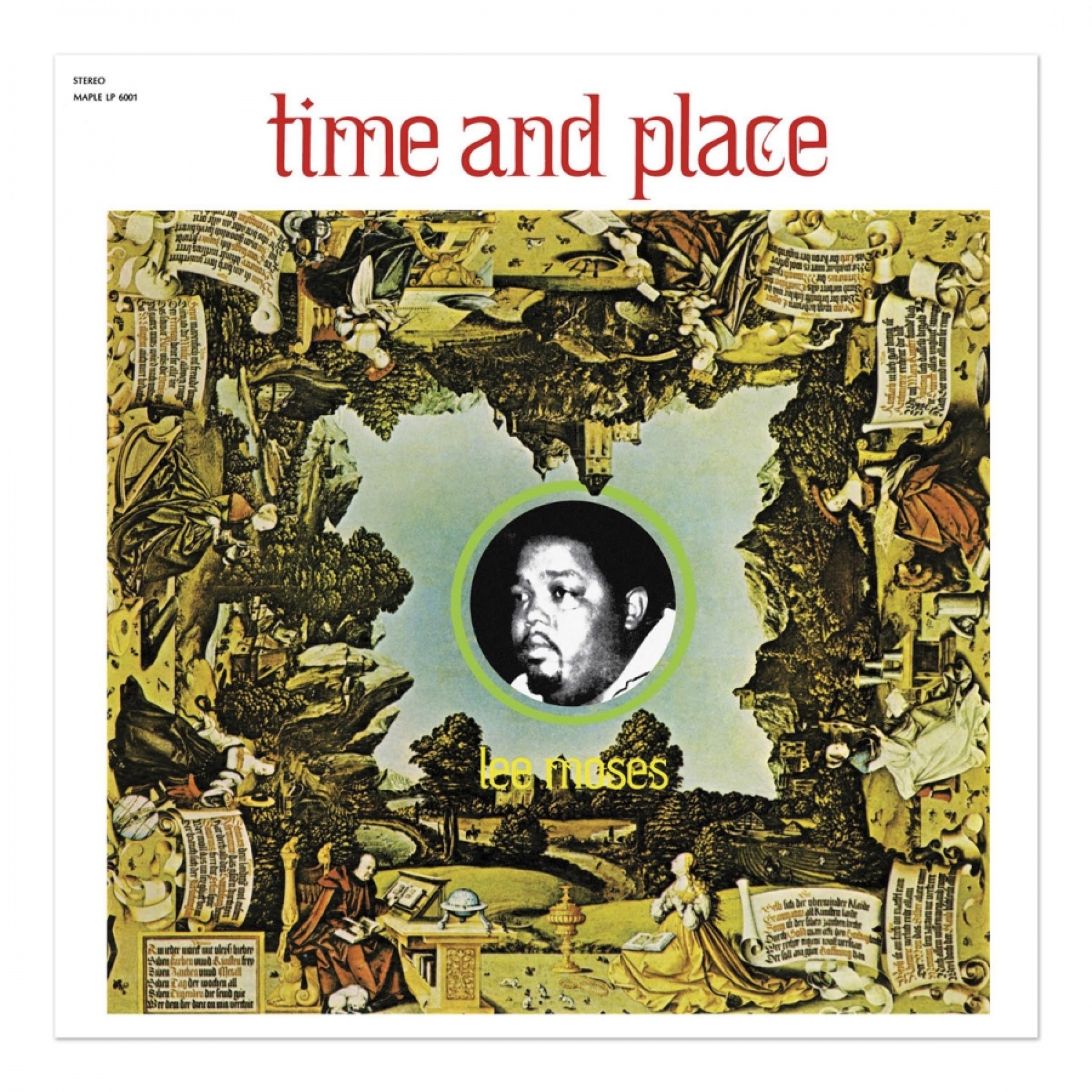

Time and Place by Lee Moses

REINTRODUCING LEE MOSES

By Sarah Sweeney

Dept. of Georgia Music discoveries

In our 2015 Georgia Music issue, Brian Poust wrote about the thriving soul scene of Atlanta’s Sweet Auburn neighborhood in the 1960s and ’70s. This week, Light in the Attic reissues the 1971 deep soul classic from one of Sweet Auburn’s most talented and enigmatic players, Time and Place by Lee Moses. This essay is excerpted from the liner notes and published by permission of the author and Light in the Attic records.

In the late 1950s, it was a common sight to find a teenage Lee Moses ambling up and down the halls of Booker T. Washington High School “blowing harmonica,” according to his younger sister, Donia. That image sits with her even today. “Playing music was all he ever wanted to do,” she says.

The Moses household had been a musical one. One of eight children, Lee sang in the church choir alongside his siblings. Their father, Joseph Moses, served in the military and played piano, performing in USO shows from time to time. According to Donia, he passed away in 1955 without witnessing his son’s musical career take off.

But Lee Moses’s career remains something of an anomaly. A multi-instrumentalist, Moses easily picked up the organ, guitar, and drums, self-teaching himself the nuances of each instrument while honing his soulful, lovelorn wail alongside musical luminaries such as James Brown and Gladys Knight & The Pips. He possessed all the ingredients for a successful career, but after releasing just one album, Moses would vanish into obscurity in his hometown of Atlanta, where he died in 1997, remaining one of the most underrated but enigmatic figures of rhythm and blues.

Try Googling Lee Moses, and you’ll find that there’s not a lot out there. Deep soul aficionados speculate up and down blog posts and message boards, but Moses’s life has remained mostly a mystery and his music a staple among cult collectors. Donia, now retired and living in Atlanta, serves as the last surviving Moses sibling and perhaps one of the last ostensible historians of her brother’s legacy.

Moses’s final known release was a version of the classic soul number “The Dark End of The Street,” which appeared as a single on Gates Records in the early 1970s. Though the track is a haunting retelling of the archetypal doomed couple à la Romeo and Juliet, the song title might be an apt metaphor for the last decades of Moses’s life.

After spending the mid-sixties traveling back and forth between Atlanta and New York as a regular session musician under the direction of producer and Atlanta-native Johnny Brantley, Moses cut his own record. He’d seen his onetime studio colleague Jimi Hendrix make it big and he knew his own stuff was good. Time and Place came out on Maple Records in 1971, and it flopped. Dejected, Moses quit New York City for good, and gave up his dreams for broader fame.

Back in Atlanta, Moses married, according to Donia. His wife passed away, but he remarried, and the couple had a son. They later separated though never divorced. Moses continued playing the Atlanta club circuit. “He’d play lead guitar and always got a job with someone else’s band,” recalls Donia. “He had a good reputation for drawing people to shows.”

But it was the seventies, and disco was king. Live acts were replaced by DJs, “but Lee was always hopeful,” says Donia. “He thought everything would bounce back, and he’d be on top again.”

Like many musicians of the time, Moses began indulging in drugs. But Moses was diabetic, and the drugs did even more damage to his system. “I think as his health declined, that threw him into depression because he saw the chances of a comeback were slimmer,” Donia says.

“I could see the pain in him,” remembers Hermon Hitson, a fellow Atlanta musician and Moses’s lifelong friend. “He was just so used to playing.”

Moses spent his last days in a wheelchair, with Donia handling his day-to-day care. Eventually, his kidneys failed, and he went on dialysis. In the hospital, Moses’s organs began shutting down, and he died in 1997 at the too-early age of fifty-six.

Hitson gets nostalgic when talking about Moses and those younger years. Like Moses’s, Hitson’s career never quite took off. “It took me a long time to understand I was just a product and that people can take advantage of you,” he says. But he speaks of how great Moses was, and innovative—taking song originals and transforming them into something wholly his own. “Lee could come in and turn a song around,” Hitson says.

And he laughs, remembering the rock festival in Atlanta’s Piedmont Park in 1969. “Lee had never played a rock festival,” says Hitson, who at the time, says he was “flowerchild to the bone,” donning buckskin and cowboy spurs, while Moses was mostly oblivious.

“He said to me, ‘Who are the Allman Brothers?’”

That night, Hitson dropped acid, and Moses, claiming nothing could get him high, took some, too. A half-hour later, Hitson turned to Moses, who was trembling and cold. “He said to me, ‘See, nothing can make me high.’ I said, ‘The train ain’t even left the ground yet.’”

When Hitson and Moses hit the stage, Hitson claims he could hardly find the neck of his guitar after putting it on, but Moses stoically performed. “He played more guitar than anyone that night.”

The next day, Hitson recalls, “they put his picture in the paper.”

Read, and hear, more Atlanta Deep Soul in our Georgia Music issue.