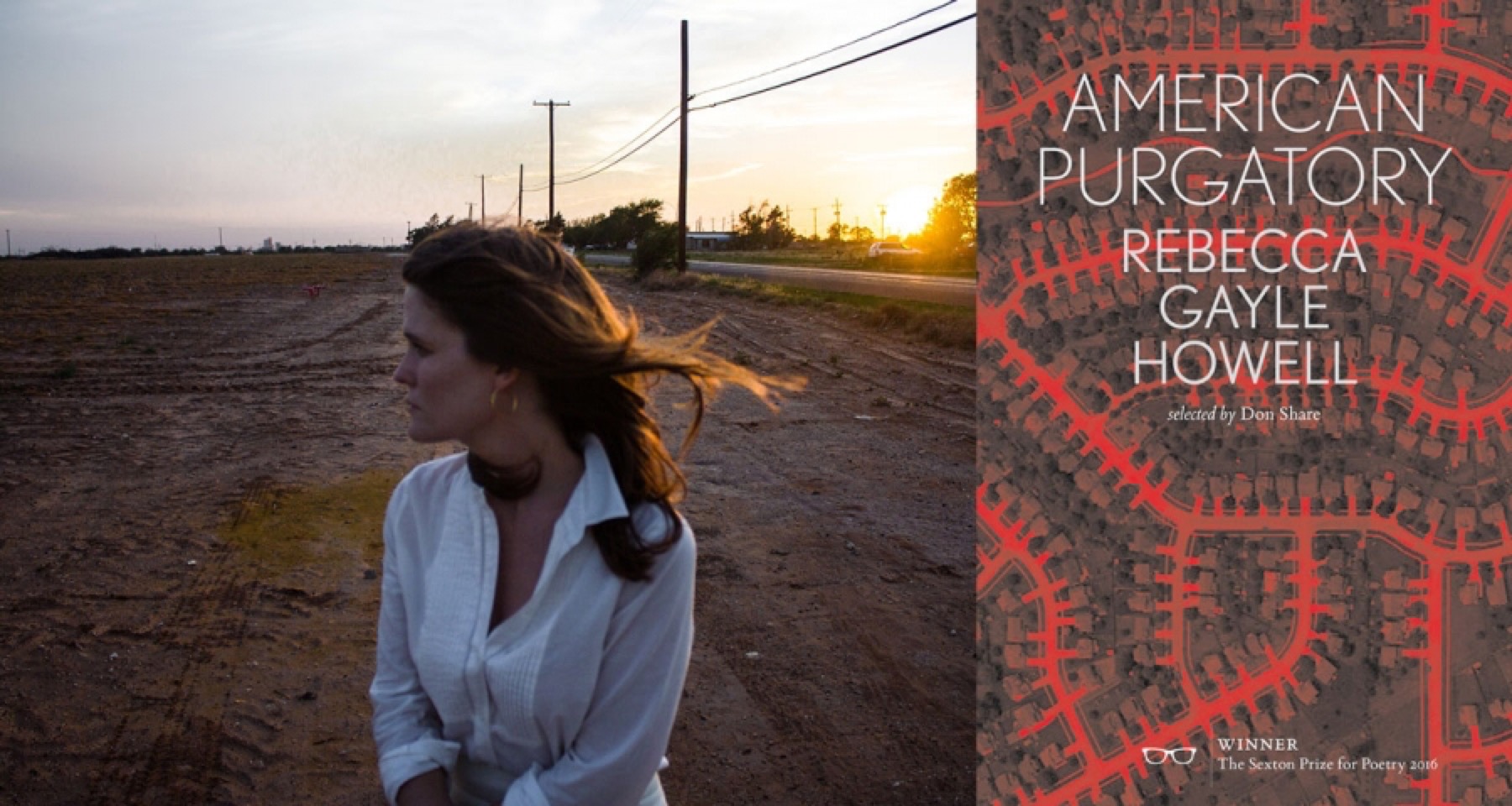

Photo by Jacob Shores-Arguello

SERVICE AND LABOR

By Oxford American

Before she became an editor of this magazine, Rebecca Gayle Howell sent us a batch of new work, five poems from a larger body of work-in-progress: “a purgatorio set in West Texas.” In the manner of her first book, Render: An Apocalypse, the new poems were lyrical, evocative, and overwhelmingly powerful in their intimacy with working-class existence. Because we couldn’t possibly isolate a few pieces from the submission, then-editor Roger D. Hodge bought the lot. The five poems were published in our Spring 2014 issue, the first dispatches from what would become the book American Purgatory, which Poetry editor Don Share selected for the 2016 Sexton Prize for Poetry from Eyewear Publishing.

“In Howell’s haunting and distinctive vision of the American South ‘No one was born here. We are persons held to service and labor,’” Share writes in his introduction, quoting the book’s opening lines, “condemned to suffering a precarious, dangerous landscape replete with worms, snakes, dust, drought, and wind.” Those first words—No one was born here—appeared in Howell’s Oxford American publication, as did some of the images, characters, and critters who animate American Purgatory, along with the dust, and the sun. But this book is a much larger, wilder, and more brutal beast.

In a review in the Arkansas Times, Jackson Meazle captures well American Purgatory’s great power: “The narrator’s elliptical interior monologues are mesmerizing meditations on natural life and existential terror—and the expression of ‘neighborliness’ shared between the narrator’s retinue ranks among the most lucid since that in fellow Kentuckian Maurice Manning’s ‘A Companion for Owls.’”

At her book launch in North Little Rock last month, Howell read through the entire arc of the collection, describing the oppressive structure of “the town” and its immobile divisions. Many lines stay with us; throughout American Purgatory, Howell doesn’t so much lament societal partitions as sharply rebuke them as plain human-wrought constructions: “The best job is laying fence,” she read from the book’s opening piece. “Everybody wants a fence. Some, so close it’s like we’re planting the post right through the middle of their feet.”

The evening was rainy and dark—a fitting background to this story. Yet in the end, we were left with a kind of hope in community and shared struggle and defiance. Howell was joined onstage by her partner, the Kentucky traditional musician Brett Ratliff, whose interpretations of old songs such as “Ain’t No Way Out,” “Elzic’s Farewell,” and “We Shall All Be Reunited” confronted similar themes of labor and protest, nudging us toward the same conclusions.

Please join us in congratulating our colleague—thank you, Rebecca.