SUSPICIOUS MINDS IN MISSISSIPPI

By Andrew Paul

Kevin Curtis lowers his sunglasses and scans the crowd. He’s just finished performing “Folsom Prison Blues” at the Lamar Lounge in Oxford, Mississippi. The audience applauds, but the mood is strange—genuine enthusiasm, curiosity, an undercurrent of discomfort. During one of the choruses, he swayed with a very supportive, very drunk woman from the front row. For the solo, he strummed a tiny guitar pin stuck on his dress coat lapel. I lift my beer toward him from the second row. He notices, raises an eyebrow, nods.

“This is the first show since my”—he pauses, presses the sunglasses back up to his eyes—“incarceration.”

Last April, Curtis went from eccentric small-town celebrity-impersonator to potential domestic terrorist overnight. Ricin-laced letters had been mailed from his address to a local judge, a Mississippi U.S. senator, and President Obama. Within a few days, the charges were dropped when evidence revealed that Curtis was framed by a local rival, James Everett Dutschke.

Despite the acquittal, Curtis is still a wanted man. A camera crew, present at the show in Oxford, is making a documentary about him. Numerous publications are still asking for interviews. He’s been a guest on “Good Morning America.” On Piers Morgan’s show, he made clear that he first heard the term “ricin” while being interrogated by Homeland Security.

“I thought he said ‘rice,’” Curtis told Pierce. “I said, ‘I don’t even eat rice, usually. I’m not even a rice lover.’”

I’ve been trying to get ahold of Curtis for weeks since his Oxford appearance. When I first reached out to him, Curtis was extremely open to the prospect of an interview, but then his e-mail responses became less and less frequent, and have now dropped off completely. I get his voicemail—“Kevin with Star Tribute Entertainment”—when I call the number he gave me, and leave a rushed, embarrassing message. I end it, “Ready when you are. Let’s get this thing rolling.” My deadline is approaching, but I can’t reach a man who appears to relish every chance for promotion in a spotlight few would want.

Curtis and his attorney scheduled a press conference the afternoon of his exoneration. Most people would thank those who supported them, leave it at that, attempt to return to their old lives. Curtis used the conference as a platform to pitch his book, an exposé on mafia-orchestrated human organ trafficking, to any interested publisher. Working title: Missing Pieces.

The national press’s coverage of Curtis is surreal. Here, he’s a blue-ribbon freak show from a state that specializes in the conception, cultivation, and exportation of freak shows—think Ross Barnett at the Neshoba County Fair, Paul McLeod and his tourist trap Elvis memorabilia mecca, Graceland Too, and the infamous Jackson mayor, Frank Melton.

The exceptions usually go unnoticed.Two years ago, Mississippi voters overwhelmingly struck down Proposition 26, the so-called “Personhood Amendment” and a major threat to women’s reproductive rights. Last year, a doctor in Jackson effectively cured an infant of HIV. This year, on a televised press conference on the steps of the Oxford, Mississippi, courthouse, Kevin Curtis offered free foot massages to his lawyers for their hard work. Three guesses as to which story got the most airtime.

My family moved to Jackson, Mississippi, from Pennsylvania when I was three years old, not intending to stay. That was twenty years ago. My parents may still be Northerners in a strange land, but I’m a Mississippian. This state is my home. I want to justify Kevin Curtis to everyone I know. I want Curtis to explain our Freak Show South. I want him to tell me that we are just in the wrong place at the wrong time, that it’s easy to look guilty when absurdity precedes us. I just have to convince him I’m worth his time.

I spend a few days bemoaning Kevin’s apparent disinterest. Finally my editor tells me, “Stop complaining about having no story. Go knock on his door.”

Lamar Lounge’s manager mentioned Curtis lives in Booneville, a little more than an hour northwest. I spend the next week trying to find someone to come with me to Booneville, and digging my phone out of my pocket every time I think I feel a vibration. There’s still a chance he could call. He could decide at the last minute to open up to me about his life, his feelings about his portrayal in the national media, how he thinks he fits into our stereotyping perceptions of the fringes of Southern society. He might even phrase all this in some unforgiving, poetic way à la Barry Hannah, Larry Brown, Lewis Nordan. Something so true I could never write it on my own. But the only time my phone vibrates is when yet another person decides to back out of the trip.

Half an hour before I plan on setting out for Kevin alone, I finally find my wingman—Liam, a friend and MFA student at the University of Mississippi, from Brooklyn. He knows little about the Kevin Curtis saga but is interested in seeing as much of the state as he can during his tenure in the South. We agree he’ll be my “photographer” for the story.

As we make our way along Highway 30, I tell a very patient Liam that I want to give Kevin Curtis his due, that this may be one of the few opportunities he’ll have at an unbiased presentation to the public—one of the few times a “Southerner” will interview him.

“I think you’re assuming Kevin cares about this interview the same way you do,” Liam says.

I shut up and we watch the fields pass. Neither of us has seen this part of Mississippi before. Every ten minutes or so, there’s a stretch of industrial wasteland—timber yards, rust-etched silos, Walmart distribution hubs. Acres of level farmland are separated by half-mile stretches of seventy-five-foot pines set in hillsides I wasn’t aware existed in Mississippi. I realize that, outside of the suburban bubble of Jackson and the whitewashed condominiums of Oxford, I’ve seen very little of this state. We pass in and out of summer rainstorms and the mists they leave behind for ninety miles until we reach Booneville.

We pull into a Pizza Hut on the town’s main street. I heard that Kevin likes chicken wings, so I order two dozen. I ask Cassie, one of the cooks, if she knows of a Kevin Curtis who lives in town.

“Elvis impersonator. Ricin. Yeah, I know him,” she says.

“Oh, wow.” My weak veneer of professionalism dissolves. “Does he live nearby?” I ask.

“He moved up to Corinth after all that went down,” Cassie tells us. “I used to work for Michael Rainey, the chief of police here. His family owns a restaurant nearby. You could try talking with him, but I doubt he’s there since it’s a Sunday. But you two don’t want to go out there.” She pauses to size up Liam in his patterned chambray and me in my button-up shirt.

“It’s twenty minutes out in the sticks. You’ll get lost,” she says.

Michael Rainey’s voice comes through as a gruff, small-town drawl when he answers the phone, a mix of Mississippi Burning, Gene Hackman, and every Sam Elliott character ever.

“You said someone named Cathy gave you this number?” he says.

“Cassie,” I correct.

“Cathy?” he asks, a little agitated.

“No, Cassie.”

He sighs so loudly that the sound crackles through the receiver. “Cathy?”

“Cassie. With an S.”

“Oh, Cassie,” He elongates the “a.” “What can I do for you?”

“I know you get this a lot lately, but I’m writing a story on Kevin Curtis, and I—”

“Nope,” he cuts me off. “There’s nothing I can say. Not while there’s an ongoing . . .” His voice weakens, mumbling the remainder of the sentence, knowing that the both of us don’t need to hear the rest of what he has to say. He’s swatted away gadfly reporters a dozen times in the past week alone. He gives me a pity lead with the city attorney’s number. I call and get a receptionist’s voicemail wishing me “a blessed day.”

A few streets over we locate Kevin’s recently vacated residence in a silent neighborhood. Kevin’s former street consists of about eight small, pre-fab houses with single-capacity carports. Usually, two or three fix-up vehicles sit in the driveways.

The first half of the street is nearly treeless, lending it a strange spatial illusion. Houses seem to stand farther and farther apart as you walk down the street, like homes situated at the edges of ripples. Trees obscure our sight beyond the end of the road, but I get the feeling that nothing else is out there. The stillness bypasses sound straight into something you feel on your skin like condensation.

The doorbell has been wrenched off Kevin’s former front door, so I knock. There’s no movement from inside. I knock once more before giving up.

As we walk back toward my truck, Liam notices a bright orange sports car from the Seventies with the vanity plate “DUKE JR.” parked in the carport of the house on the left. In faded, hand-painted lettering on the mailbox is the name “Curtis.”

Maybe I got Kevin’s address wrong. I walk over and knock. A teen in pajama pants opens the door. I spout the same introduction I’ve rattled off to everyone on our trip.

“I’m sorry, I know you’ve probably gotten a million people asking about Kevin Curtis,” I say.

“Eh, it’s not all that bad.” The kid shrugs it off like a tired pro. A younger child lies on the couch behind him watching television. He doesn’t acknowledge any of the conversation.

“Is your mom or dad home?” I ask.

“Mom!” the kid calls out.

A friendly-looking woman in a light pink Northeast Mississippi Community College T-shirt comes to the door and we shake hands. She introduces herself as Laura, and we start to talk about Kevin.

“Kevin moved up to Corinth after he got out of jail. He’s up there, mostly,” she tells me. “But he mentioned you all to me a couple times. Said you were trying to interview him. He was back and forth about whether or not to get in touch.”

“We were just passing through, and thought we might see if he was still around.”

“Well, Kevin is the sort of man who loves to talk about these things for a few days, and then he just won’t leave his house for a week, you know?”

“I think so. We initially thought the house next door was his place until we saw the mailbox here,” I say.

“Oh, it was,” she replies, surprised that I believed otherwise.

I’m confused, and try to figure out what to say next. Laura beats me to it.

“I’m his ex-wife,” she says.

“Oh. Damn,” I say.

“We decided to live close after we split up. That’s why ‘Curtis’ is still on the mailbox.”

Laura is patient, doesn’t seem at all bothered that another couple of strangers have shown up asking for her ex-husband. I leave my name and number, but she doesn’t offer an exact location for Kevin in Corinth. I get the feeling she’s had a good deal of practice being polite lately.

“I’ll let him know you were by next time I talk to him,” Laura says. It’s time for us to leave.

Liam and I eat twenty-four soggy chicken wings in the parking lot of a one-pump gas station-turned-barbecue joint.

“Well, at least she said she’d tell Kevin,” I say, throwing a chicken bone out the driver’s side window.

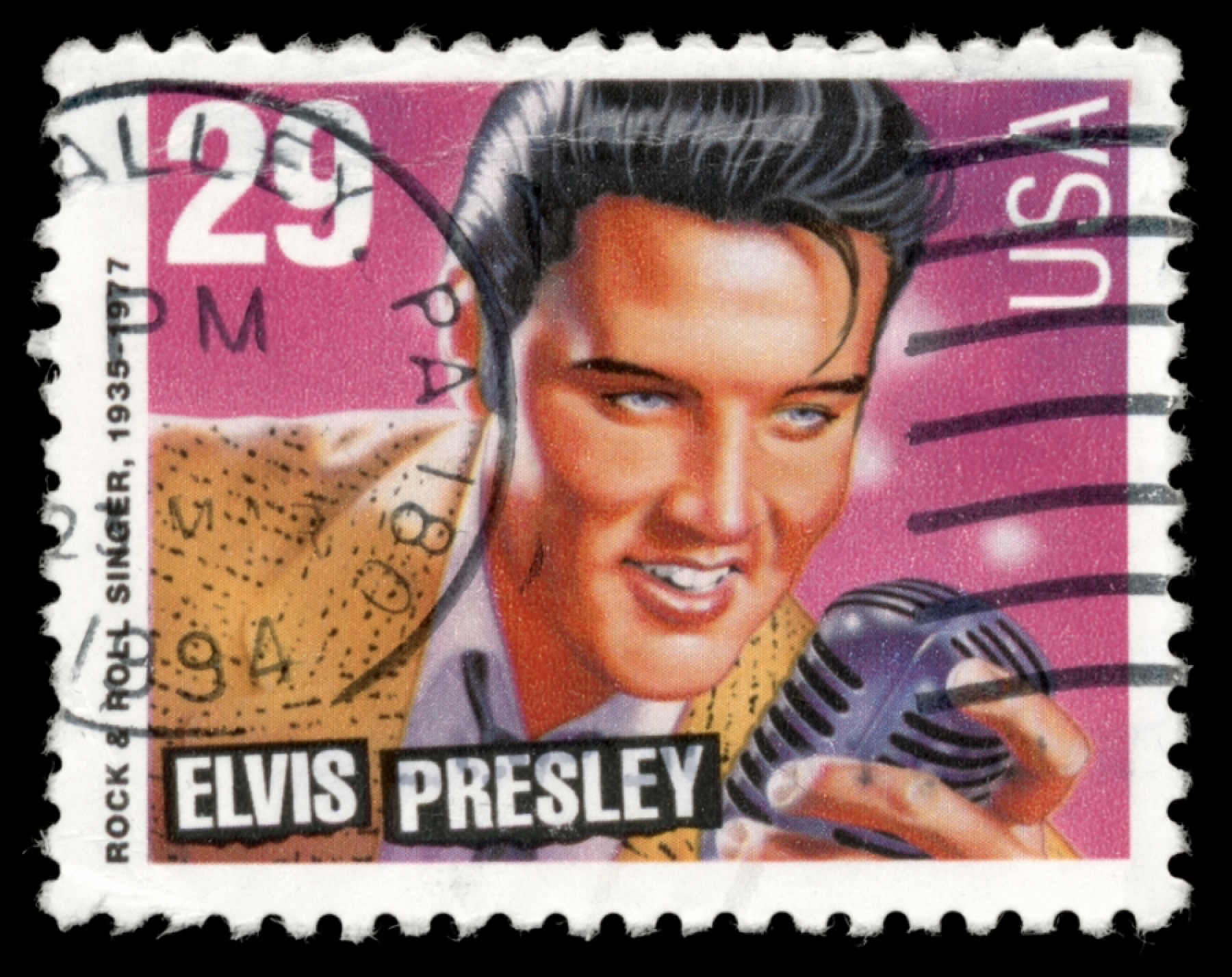

Liam nods and searches for a napkin. We eat until we feel sick, and then take the interstate through Tupelo. I realize I know nothing about Elvis Presley, and am glad Kevin never found that out.

Kevin Curtis at a press conference.

Kevin Curtis at a press conference.

I’ve slept lightly in the few days since Booneville, so I wake up instantly when my phone buzzes with a message at four in the morning. It’s a number I don’t recognize, but I immediately know who it is.

“Is it too late to interview?”

The next day I leave Oxford for Corinth alone.

The drive to Kevin’s house resembles the failed excursion to Booneville.I pass by Abbeville’s Bette Davis BBQ, a damp lean-to situated on the Lafayette County border. I drive through Holly Springs and its derelict town square lined with sun-bleached American and Mississippi state flags, through Walnut, Hudsonville, Michigan City. I pass a sign for a town named Canaan. The smell of wet asphalt comes in through the air conditioning vents, and I feel a strange sense of isolation as I make my way north.

Kevin lives on the edge of Corinth in an unfinished subdivision. Any trees here are saplings, and the land rises just slightly enough to see the houses of surrounding streets around his home’s cul-de-sac. It’s quiet, but one can hear the distant, unmistakable sounds of living. Construction, lawn mowers, car doors.

A truck parked in Kevin’s driveway features a swiveling dashboard Elvis. A printed-out, homemade cover for Missing Pieces, Kevin’s unpublished book, sits on the dashboard. Four security cameras top each corner of the house. “No Trespassing” signs are posted in every window. Like his house in Booneville, the doorbell has been pried off. A twenty-five-pound stone balances on a front sill. It’s painted in black-and-white horizontal stripes, and I stare at it for a moment before it finally sinks in—Jailhouse Rock.

I spend fifteen minutes in the brutal afternoon heat knocking on Kevin’s locked, industrial-grade screen door. He mentioned I might have to do this—he’d been up for twenty-four hours since we last spoke, and was going to nap until I arrived. Through the metal mesh I can read a handwritten note taped to the door: Please DO NOT Bang on doors + windows. May Be Sleeping . . . or Making “Rice.”

I’m sweating through my shirt by the time the door cracks. There is no light inside, and I can’t see through the opening. A bleary-eyed man in undergarments and a robe emerges. Kevin Curtis smiles as we shake hands, and I introduce myself.

“Hey there. Thanks for driving up all this way,” he says.

He steps aside to let me in. As he closes the door behind us, the room darkens again.

I hear Kevin shuffle across the floor. Things gradually come into focus. The dim green glow from a lava lamp in the corner is helpful. A table lamp clicks on, and the room materializes. The living area is cramped and the furniture in it is small. Five or more Marilyn Monroe paintings hang on the walls, along with a couple Elvis Presley portraits. Kevin sits on the sofa and a small white dog with black spots jumps up next to him. I take a seat on the nearby ottoman.

“This is the infamous Moocow,” he says as the dog settles in his lap. (One of the focal points of Kevin’s press conference was a plea for the safe return of his dog, who went missing during his arrest.)

Kevin already looks more alert and awake. He seems eager, excited to talk to someone. This is a man who has made the most of his sudden fame. He looks down and smiles at the dog, and I notice his shark-fin sideburns. It’s then that I realize just how comically underprepared I am. I’ve spent the past month obsessed with tracking down Kevin to make him explain himself, and by extension the freak South—two subjects few people have been able to comprehend. I’ve been complicit in the tired storyline I believed I could avoid. I thought I could avoid mythologizing this man, talk to him as a regular person. Now that I’m here, I don’t know what to do with this white whale.

I stutter into my first questions.

“Everyone’s covered the trial and the ricin and stuff. All that stuff has been covered. I’m more concerned with you,” I say, noting that it’s only taken me three sentences to sound like a jackass. “Because it’s Mississippi, we’ve already got the cards stacked against us. They’re already looking for something.”

“Today is the first day that I’ve had sound on my computer since I got out of jail,” he says. “For some reason, the Feds, when they took my computers, they destroyed them.”

From here, Kevin veers into his account of a thirteen-year odyssey, one that stretches from working as a janitor at the North Mississippi Medical Center to finding fridges containing “hundreds of body parts wrapped in plastic with barcodes” to being blacklisted and stalked by shadowy forces. My dreams of having Kevin Curtis explain Southern identity quickly evaporate as he delves deeper into his story.

“I haven’t had any kind of medicine in twenty years. My family has gone on record and said, ‘Yeah, he’s bipolar.’ And my ex-wife said it,” Kevin says as Moocow moves to a cooler part of the couch. “If you think outside the box in Mississippi, and you question, then people tend to think you’re different.”

Kevin has spent the last decade attempting to alert the public to what he believes is a massive cover-up involving regional medical facilities, funeral homes, doctors, and politicians, and extending to organized crime. The post-acquittal publicity has allowed him to further promote his “House Resolution Bill 6631,” which would reform the regulation of the organ donor market—the specifics of which he never quite explains.

His history is fragmented, with varying degrees of clarity and credibility. The family he once had. Cars exploding. Lives he’s saved. Threats on his life and his children’s. Police harassment. Elvis-impersonation festivals. Names come and go. Time skips back and forth between dates across the past fifteen or so years. It’s dizzying, but Kevin recounts these fissures of memories in such a way that I never lose interest.

If nothing else, Kevin Curtis is one hell of a performer.

Multiple times during my visit I look up from my notes to see Kevin gauging my reaction to his various claims. He seems sincere and I can only nod in hopes of conveying an unspoken sympathy.

I try adapting my questions to his increasingly complex story. During a lull I ask him if he’s okay with the fallout that comes from exposing the Southern medical community’s hidden, nefarious truths.

“The fallout has been coming for thirteen years. I’ve been arrested twenty-something times, and I’ve never been convicted of a crime yet. They came real close this time. I came real close to getting framed and going to prison for a long time,” he says, acknowledging the ricin incident.

“Do you think there were other powers involved?” I say.

“Other than?”

“Other than Everett Dutschke?” I ask.

“You know I do.”

“You think so?”

“I know so. I’ve researched it to a science, and you’re not going to prove me wrong. I know what I know. It’s a conspiracy. That word is never going to change. It’s a conspiracy.”

Another gauging glance. He’s not simply judging my reaction to his story—Kevin is evaluating his conviction based on my responses. He knows what he knows. Or at least he thinks he knows what he knows. Recounting these past thirteen years to an audience allows him the chance to reinforce his story’s truth. When I start to show any doubts, he redoubles slightly. When I ask questions about the shadowy muscle men and corrupt cops, he grins and pushes on through.

It’s been nearly an hour and a half. There’s not much else to say to Kevin. Nothing I can think of saying, at least. I begin to gather my things to leave. He’s not interested in my nebulous anxieties. He’s got his own. I ask one more thing.

“Would you say you are happy in any way now?”

“Am I happy?” Kevin laughs.

“I know it’s a hard question to—”

“Oh, it’s not a hard question. It’s very easy. I’m very unhappy. I’m very unhappy. I’ve lost everything in my life because of—” Kevin pauses to collect his thoughts. “Lost my marriage, my music, my home. Everything. And so far the media has shadowed this out and it’s been like, ‘Elvis impersonator.’ That’s the only thing you hear. And it’s insignificant to me. I’m living life like Elvis Presley did before he died. I sleep in the day to hide from the world because of what I face when I walk out that door.”

I thank Kevin for his time. I pat Moocow before leaving the house. Kevin opens the door, and the late-afternoon sunlight makes it difficult to see. I shield my eyes with my left hand, shake Kevin’s hand with my right, and tell him I’ll see him soon. In two weeks, he is set to play a full set back at Lamar Lounge in Oxford.

On the road back to Oxford from Corinth, I get caught in a flash summer storm. Traffic slows to a crawl, and my windshield wipers barely keep up with the rainfall. I pass by the exit for Canaan, and think of Job, a man who was stripped of everything he once had. I think of Kevin, troubled by a malevolent force beyond his control. Black-market organ harvesters, James Everett Dutschke, bipolar disorder, the press. It doesn’t matter what shape it takes. The only thing I know for sure are its visible effects on Kevin—the paranoia, the fear, and the hope for salvation that come from being marginalized, from when your life is reduced to a tired punch line.

A few days before the show, I notice that I haven’t seen any fliers or promos. The local newspaper doesn’t list anything at Lamar Lounge. I remember what Kevin told me as I left his house a couple weeks back. I’m living life like Elvis Presley did before he died. My anxieties get the better of me, and I text him:

“Hope everything is well. I saw there isn’t a show scheduled at Lamar. Did it get cancelled?”

Within five minutes, I get a response. Kevin tells me that Big E, the local Oxford Elvis impersonator who invited Kevin to guest spot at the first show, “stirred up drama and brought management into it.”

“LOL . . . I had to laugh,” he adds.

I tell him I’m sorry to hear that, and that I hope he gets a show booked soon.

“Same here . . . truuuuust me . . . the SHOW will not only go on . . . it is bigger and better than ever before!”