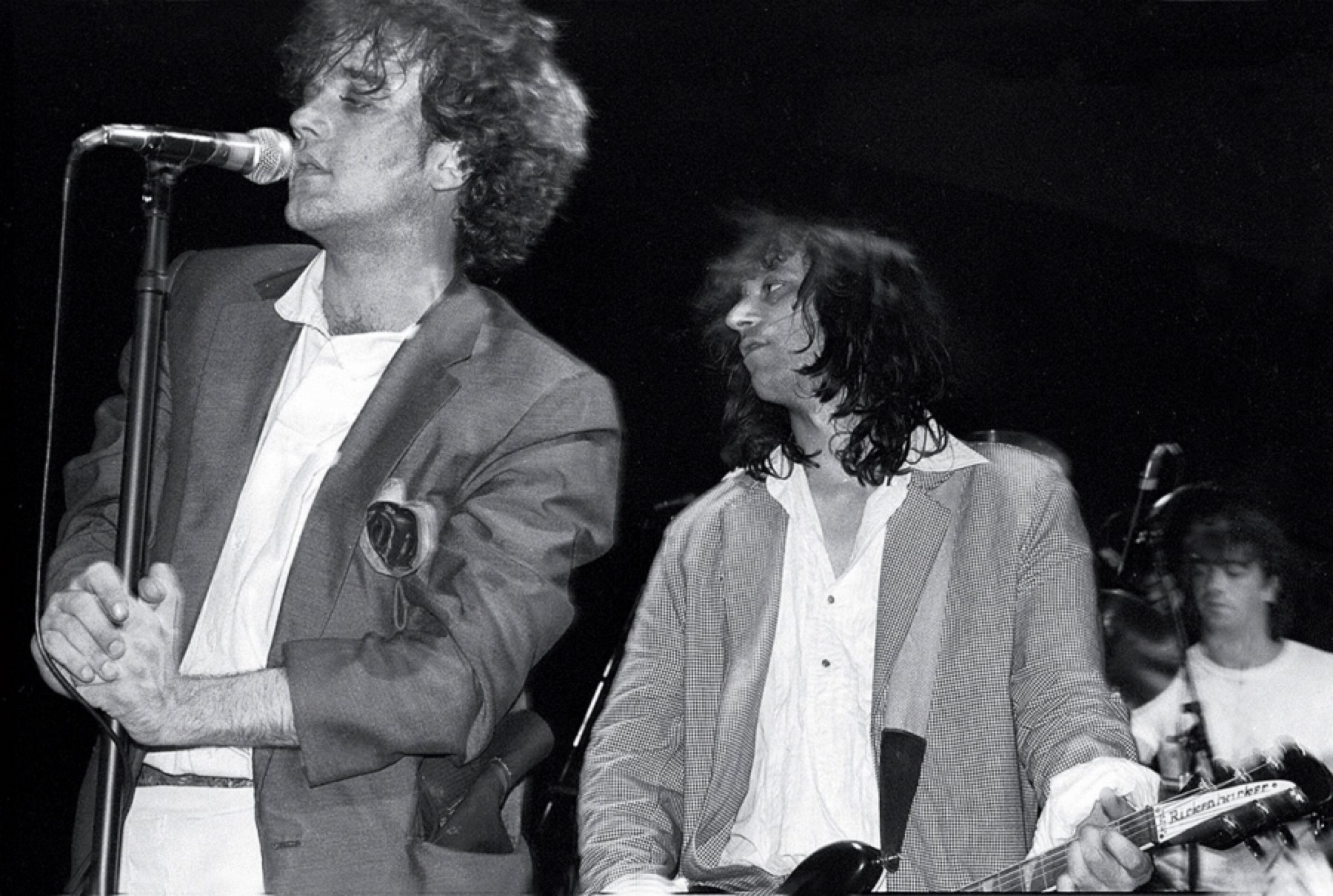

Michael Stipe, Peter Buck, and Bill Berry of R.E.M. at the Saenger Theatre, New Orleans, September 1986. Marty Perez / Smithsonian Books

THAT FINE, FINE MUSIC

By Bill Bentley

An Index of Supreme Influence

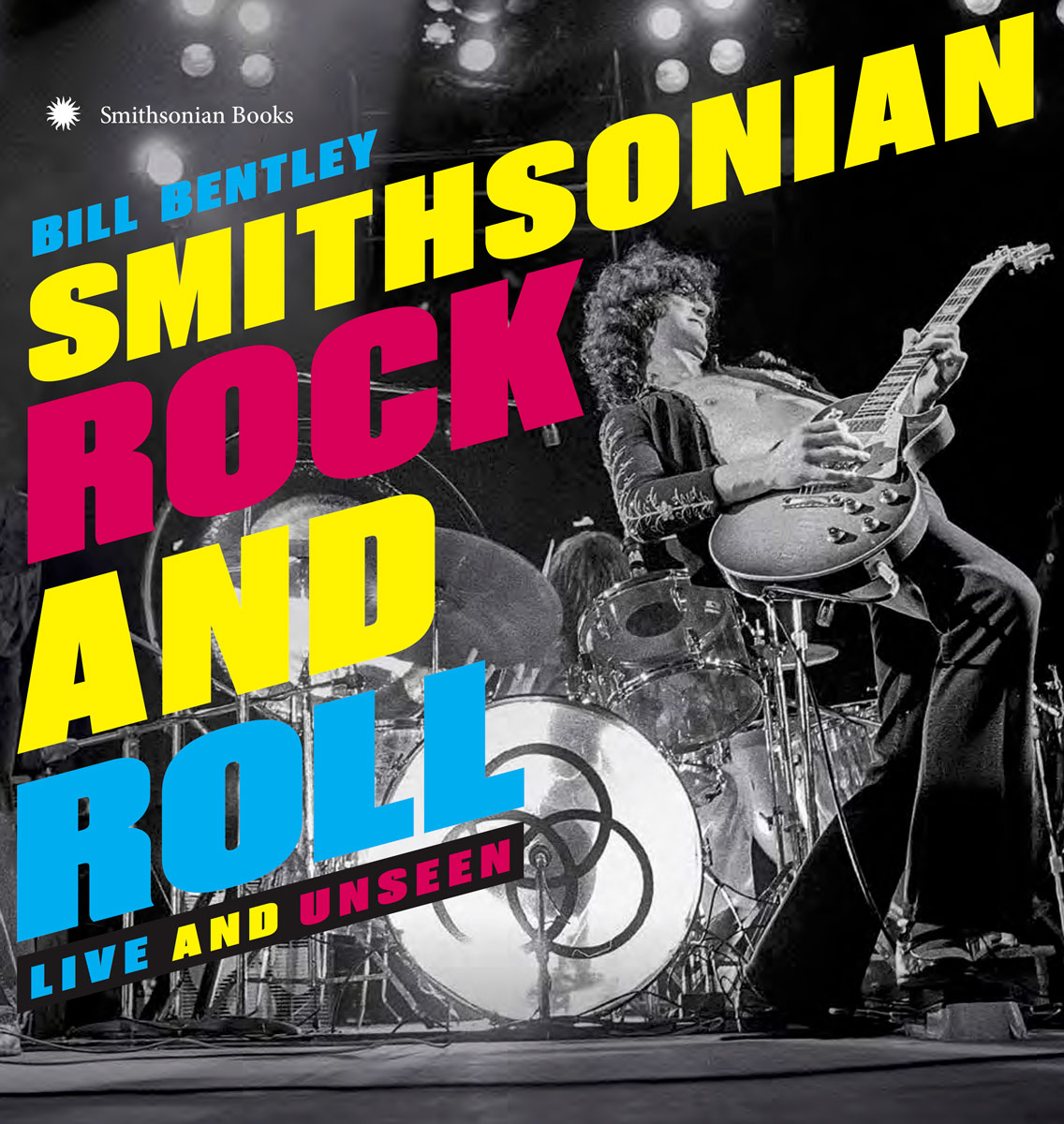

The introduction to Smithsonian Rock and Roll: Live and Unseen. Reprinted by permission of the author and Smithsonian Books.

On Sunday mornings, I often visit a big white building at the corner of Sunset Boulevard and Cahuenga in Hollywood. Decked out in 1950s-fashionable neon, and looking vaguely nautical with a submarine-like periscope rising behind its facade, it borders on the otherworldly when I walk in at 11 A.M. A vast expanse of vinyl albums, compact discs, cassette tapes, and books fills the ground floor, and posters in saturated colors from every era clamor on the walls. Here at the western edge of the United States—the country that birthed blues, jazz, gospel, and rock & roll in all their permutations—Amoeba Music could be the best record store in the galaxy.

Strolling into Amoeba one morning, I was greeted by a Velvet Underground collection playing at top volume, rearranging the molecules of the store and its first wave of customers. A tribal stomp rippled along the aisles and behind the counters, “Sweet Jane” and “White Light / White Heat” washing over one and all. When the sounds of the spheres possess you, they fill every corner of your soul. Then “Rock & Roll” came on, one of the last songs the group recorded before breaking up in 1970. Lou Reed sneers a challenge as he sings, “Jenny said when she was just five years old / There was nothin’ happenin’ at all.” For many of us, that’s how life felt before rock & roll arrived. I was just five myself in July 1956 when Elvis Presley went nuclear on “Hound Dog,” a primal howl out of Memphis, Tennessee, that would change the world in a head-spinning chain reaction. Jenny’s life is “saved by rock and roll,” but rock didn’t save our lives as much as make them. A constant companion and confidant, an unshakeable shoulder to cry on, and a celebrant at every crucial juncture of life, the music never lets us down.

Countless tomes have been written about “Hound Dog”’s release more than six decades ago. It was the watershed moment at which rock & roll crossed over old genre boundaries and began to establish its global dominion. In the United States, the music spoke to burgeoning younger generations, who glimpsed in its sound newly flowering freedoms. There could be no going back; the genie was permanently out of its bottle. The soundtrack to a new youth revolt had cast its spell upon everyone within earshot. Those masses of fans, in subsequent years, made rock & roll. Collectively, they are rock & roll. Without them, the history of rock is just notes and voices ricocheting around an empty room.

Together fans have worn vinyl down to a nub, unspooled eight-track tapes and cassettes into spaghetti, spun the shine off CDs, and downloaded countless hard drives’ worth of MP3s. Memorized every last blessed lyric while hanging posters on their walls from dorm rooms to castles. Tattooed band logos onto their triceps, camped out ’round the clock for concert tickets, labored long and feverish hours over mixtapes and playlists full of love and heartbreak, covered their vehicles in bumper stickers and their refrigerators in handbills, belted out choruses in the shower, and hummed melodies while waiting in line at the DMV. And they have taken photographs: millions and millions of images of their beloved musicians and singers. That ubiquitous festival shot used as a laptop screensaver says it all.

That’s where Smithsonian Books enters the picture—literally. Trade and academic press all in one, satellite to a mother institution founded in 1846, the imprint hosted a website in 2015 to crowdsource fan photographs—personal and unpublished—to include in an overview of rock & roll as seen from the vantage point of its patrons. Thousands of submissions were uploaded over the next year. From professional-quality shots taken on film stock to digital mobile phone snaps, the entire spectrum of rock photography filled Smithsonian servers.

Although the sheer breadth of the offerings was overwhelming, that fact only underlined the importance of an organizational strategy. The publisher sorted through the submissions, categorizing them by performer and date to create a complete historical timeline of rock & roll. Approximately three hundred photographs are included in the following narrative, many of them by amateurs whose enthusiasm and passion for their subjects are here presented to the public for the first time. The balance of the photos were taken by professional “lens whisperers,” whose shots were selected to flesh out this overview of rock & roll. The results, spanning seven decades, aim for neither encyclopedic authority nor comprehensive finality, but rather an index of supreme influence. Artistic importance isn’t the same as popularity, as this guided tour of rock & roll proves at every turn of the page.

Some performers included in these pages—such as the Beatles and Jimi Hendrix—cultivated both artistic influence and mass appeal. Others might not have won as much name recognition but nonetheless stamped a timeless imprint on rock & roll. Laura Nyro’s name, for example, does not carry the social import of Janis Joplin’s or Madonna’s, but her songs of devotion, by now all but canonical standards—“Wedding Bell Blues,” “Eli’s Comin’,” “And When I Die”—drill right down into the center of existence. The 13th Floor Elevators, who invented psychedelic rock, aren’t as well-known as superstars such as Jefferson Airplane, yet their small and fervent following underlines the fact that cult performers as well as icons have shaped the music.

Other performers shown here, one could argue, inhabited realms outside the stylistic boundaries of rock & roll. Yet myriad pioneering musicians such as Johnny Cash, Otis Redding, and Marvin Gaye were an essential part of both rock’s founding and its evolution; they as well as those more easily categorized as “rockers” conceived so much beauty and power in their sound that they shaped every popular musician who followed them. If rock music stands for anything, after all, it’s freedom.

From the start, it was a given that this book would open with Elvis. He didn’t invent rock & roll, but he remains its Johnny Appleseed. After the singer jumped ship from small Sun Records in Memphis to mighty RCA Victor, “Hound Dog” bawled out a blueprint for everything the new music could do. A whole army of rockers, many forged in the barn-burning bravado of urban blues, also staked out their provinces in those early days, including Little Richard, Chuck Berry, and Fats Domino. Their music became an invitation to people of all colors and classes, telling them they could meet on the great common ground of sound, learning shared lessons while burying their divisive fears. Music became an equalizer, imparting social lessons in the name of boisterous fun.

Of course, the music was also immensely profitable. And wherever huge amounts of cash turn waters red, monolithic corporations snap up the meal, both the big fish and their pale imitators, to capitalize on trends. Yet whenever rock has turned too commercial, wild-eyed alternatives have appeared. Such was the case in the 1960s when the prodigious generation of World War II blitz survivors flooded into American music. As the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and other card-carrying members of the British Invasion injected nirvana-inducing zeal into their blues-folk-country-derived pop and rock, the countercultural revolution, and rock itself, offered listeners a new prospect of individualism. Visions were encouraged, outrageousness was rewarded, and utopia was expected. The times really were a-changin’, as Bob Dylan, the era’s poet laureate, chronicled. Motown and San Francisco psychedelia—including the Grateful Dead, Santana, and Sly and the Family Stone—rewrote the rules of music, expression, and community. Rock barreled on an express train to the outer limits, breaking through boundaries into unexplored dimensions, right up until the Woodstock festival proved to be the end of the line. Now yin had met yang. There was no place left for rock to travel, except inward.

Thus the 1970s trawled a less frenetic frontier. James Taylor, Jackson Browne, and Joni Mitchell focused on emotion more than experience, and the rock audience followed them and their acoustic guitars indoors. As always, it took only one or two artists to blaze a different path and blow down the gates again, which is exactly what Led Zeppelin and heavy metal did. Huge amplifiers and elaborate stage sets dominated the mid-’70s scene, and just when every excess had been evidenced, the Ramones got back to basics. Punk rock fused simplistic riffs with riff-raff appearances, but after the Sex Pistols imploded and took much of the subgenre with them, the music lit out for new territories. Rock & roll thrives on that principle. Try to pin it down, and it will escape pigeonholing and become groundbreaking. Or just peek into the brand-new bag called hip-hop, which in the 1980s remixed everything under the sun and made the music new.

Prince, the Beastie Boys, and U2 brought musical genius onto MTV and ruled the world with images as well as sound. Megastars including Michael Jackson and Bruce Springsteen erupted at all frequencies, and the coffers of record labels needed daily remodeling to hold the earnings. Sales in the millions became the new norm; although N.W.A. didn’t display obvious commonalities with Guns N’ Roses, each fortune-earning group drew streetwise inspiration into the mainstream. That broke the music wide open again, and the 1990s saw alternative music from bands such as Nirvana, Pearl Jam, and Green Day thrive. Nature has a righteous habit of stemming such waste, and in this case the correction mechanism appeared in 1999 in the form of Napster, a free downloading service. Omnipresent almost overnight, the service was short-lived but indicated that in the age of the Web, all bets were off. As music executives soon learned, you can’t beat free, and by Y2K, the major-label paradigm had begun retracing the steps of the Roman Empire. The premillennial party Prince predicted on 1999, it seemed, had come to pass.

Zac Cockrell, Brittany Howard, Steve Johnson (drums), and Heath Fogg performing as the Shakes for the first time at Egan's Bar, Tuscaloosa, AL, July 10, 2010. David A. Smith / Smithsonian Books

Zac Cockrell, Brittany Howard, Steve Johnson (drums), and Heath Fogg performing as the Shakes for the first time at Egan's Bar, Tuscaloosa, AL, July 10, 2010. David A. Smith / Smithsonian Books

Happily for all but doomsayers wearing placards on Fifth Avenue, the world didn’t turn into a puddle with the new century. Neither did rock. Instead, do-it-yourselfers came to the forefront and demonstrated that musicians could operate without corporate behemoths calling all the shots and controlling the future. The Internet turned over the aesthetic and economic reins to artists, and even as record sales shrank and money got tighter, it felt like the 1950s again, when gamblers and go-getters ran the music business and sheer talent was the most important part of the equation. A business grown bloated and beleaguered discovered it could survive even if the fluff had to be trimmed off the top. The wild success of Adele, who transcended U.K. singer-songwriter pigeonholing at nineteen with her operatic oracle of a voice, is evidence that the “trickinations” (as Bob Marley might’ve said) of big-label promotion can be cleared away by the more democratic winnowing process of downloaded music.

And that is the end point of our journey through the images of rock & roll. It is also, of course, the starting point of a new story of rock, one whose contours and faces we have yet to see. Even six decades after rock & roll’s founding, we’re still like Jenny, the five-year-old, when she turns on that “New York station” and hears rock & roll for the first time: “She started shaking to that fine, fine music / you know her life was saved by rock and roll.” That sound, those feelings, that freedom: that’s what Elvis promised in 1956, when blues and country comingled like firecrackers and the Fourth of July. No one knew then that a seismic shift was just around the corner, and even now no one can foretell where rock & roll is headed. No matter what the powers that be predict, those plugged into the divine power of rock & roll sense that not all its hands have been played. That’s the beauty of the music—the surprise is always waiting out there somewhere. And when it hits, we’ll all be shaking.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to read more.