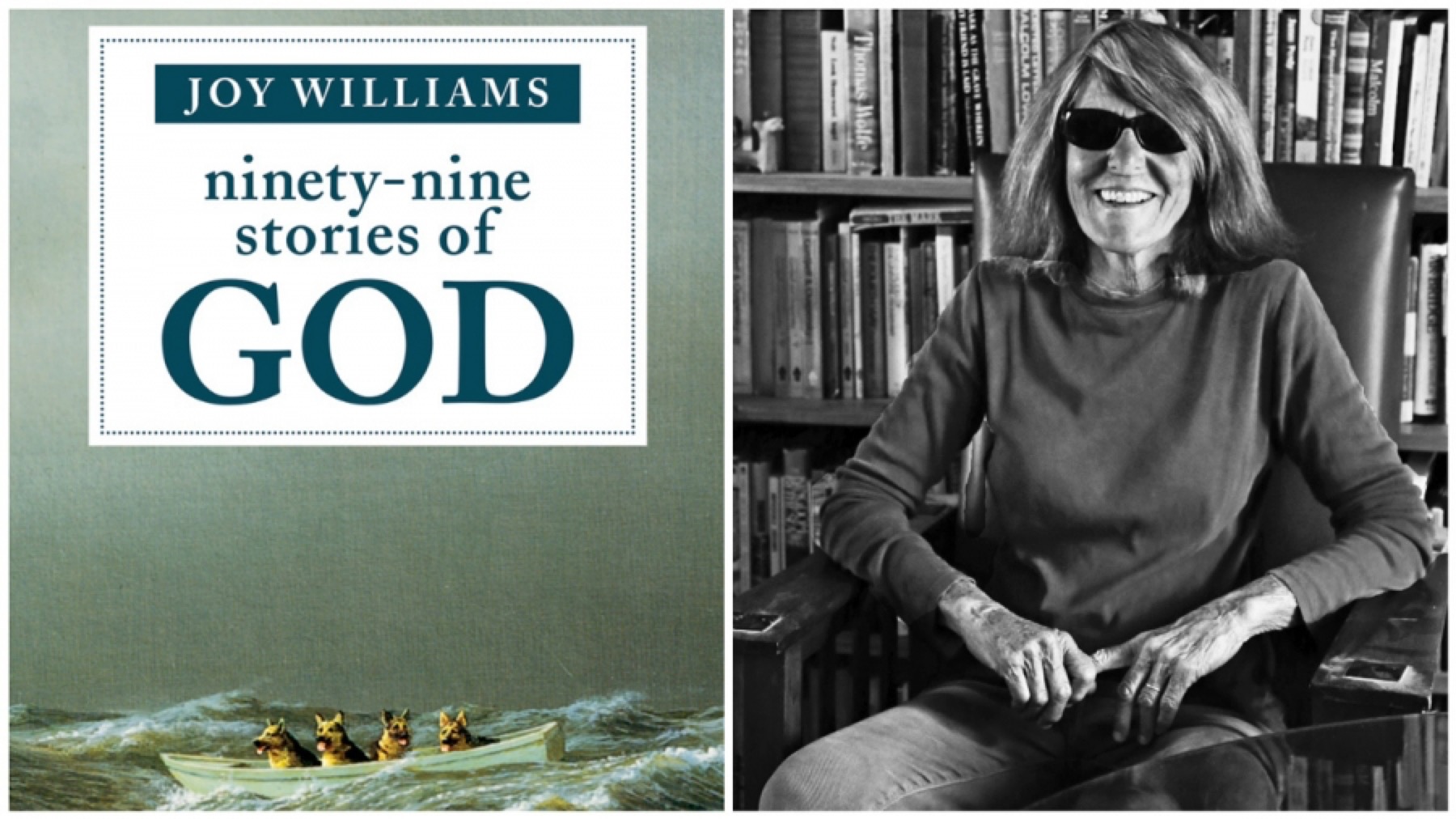

99 Stories of God by Joy Williams is out today from Tin House Books

THE LOST COSMONAUT

By Matthew Neill Null

99 Stories of God, by Joy Williams

Tin House Books, July 12, 2016

A few years ago in Provincetown, I attended a reading by Joy Williams, and after she read a certain line (if memory serves, about Gurdjieff caressing a live snake, a process both found salubrious), the audience laughed. Williams glanced up from the microphone, a bit startled. “Thank you for laughing,” she said. “They don’t always know when to laugh.”

They don’t always know when to laugh. Contemporary fiction writers can play hard for the joke, as if writing to a laugh-track, but Williams’s humor is darker, subtler, more in line with the humor of Faulkner or Isaac Babel: bracing, unsettling. The joke always teases at an essential truth about how humans live and treat one another. Entertainment is not the point but a welcome byproduct. A particular favorite from 99 Stories of God begins, “One of the schools I attended as a child arranged for our class to visit a slaughterhouse. This was both to prepare us for what the authorities called the real world as well as to show us what real work rather than intellectual labor sometimes consists of.” If the joke is caustic, so be it. Soon the story swerves in a pleasing fashion. I won’t give away the punchline, which is also its title.

In a nice act of rescue, Tin House Books today released a paper edition of 99 Stories of God in (it must be said) a handsome hardcover. An e-book original was first published by Byliner in 2013, when those charmless little tablets were all the rage—a fact most frustrating to those of us who have been loyal to papyrus and had no way of reading what was the first new fiction in a decade by Joy Williams, a master of the short story.

In the seventy-first story in 99 Stories of God, a child and a lion wander through a fog, discussing near-death experiences:

“I was possessed, overwhelmed, consumed, filled by a blessed, utterly unknown presence,” the lion said.

“Was it…” the child hesitated, searching for the right word. “…consoling?”

“Yes,” the lion said. “An inexplicably consoling irony filled my heart.”

This exchange is the book’s keystone. These parables are preparing us for death, for the ensuing brush with the inexplicable (for Williams, a believer, the Lord), but there’s much laughter and pathos along the way. When He’s not visiting drug stores, hibernacula, and hot dog–eating contests, the Lord takes part in a demolition derby, in a sentient and worried pink Wagoneer. A student of literature has the epiphany to abandon the intellectual life after being forced to shit in the Russian woods, “so shocked at the long, glistening coil of blond excrement.” Other parables are pulled from real life, whatever that means. The jurors at the O.J. Simpson trial find incontrovertible DNA evidence “boring.” Ted Kaczynski’s spare typewriter is auctioned for over eleven thousand dollars. Jakob Böhme and James Agee, Swedenborg and Sartre haunt the stories, uneasy specters.

99 Stories of God is, to my ear, Williams’s most explicitly funny book. Which is interesting. The narrator—Joy Williams? her avatar?—speaks to the reader directly about concerns of faith, mortality, and environmental devastation that are treated more elliptically in her other, more traditional works of fiction. The trappings of American fiction—dialogue, character, scene—are stripped to the bone, allowing for terse exchange, with less cushion between writer and reader. It loosens her up. Which is truly the opposite of what I would have expected from such an approach. There’s no way to discuss this book without mentioning structure, so here it goes: the reader will find ninety-nine stories, most running just a few paragraphs, some a few sentences. (Williams has noted the influence of Thomas Bernhard’s The Voice Imitator.) Each story is numbered, but the ‘true’ title appears at each story’s end, sometimes as a punchline, sometimes as a thesis statement, but most effectively as a screwdriver that turns the reader’s conception of the story at a radical angle that forces one to reorient and re-approach the work, to read the brief missive again, as in “Get Out As Early As You Can” or “Neglect.” Like poems, the best of these stories merit immediate, multiple re-readings.

While Marilynne Robinson (stately, assured) is so often held up as the major Christian believer in American letters, I would argue that, along with Annie Dillard, Joy Williams is the true seeker. Her stories are probes sent out into the universe, exploring God like a new planet, taking soil samples, comparing topographies, breaking paths for the rest of us. Faith is terrifying. To be a believer is to be a lost cosmonaut, circling out there in the cold. One’s fate is still in question. The Lord may or may not intercede at the moment of need, and isn’t that the brutal question all believers should live with? No matter how you love Him, He may not pull you from the smoking wreckage. Your children will wail. Williams faces this truth. Nothing is assured.

One is tempted to read these stories one after another, breezing through, but they are best taken singly, with time to savor the after-effects. Each story is a shot of bourbon, a tiny cup of espresso, a syringe of an essential drug. The immediate take is biting, yes, but it prepares one to face down the terrifying day or night ahead. Wipe the blood away. Wait for the singing warmth to fill you.

Enjoy this review? Order more great reading from the OA archive.