THE VOCATION OF UNHAPPINESS

By Eric Benson

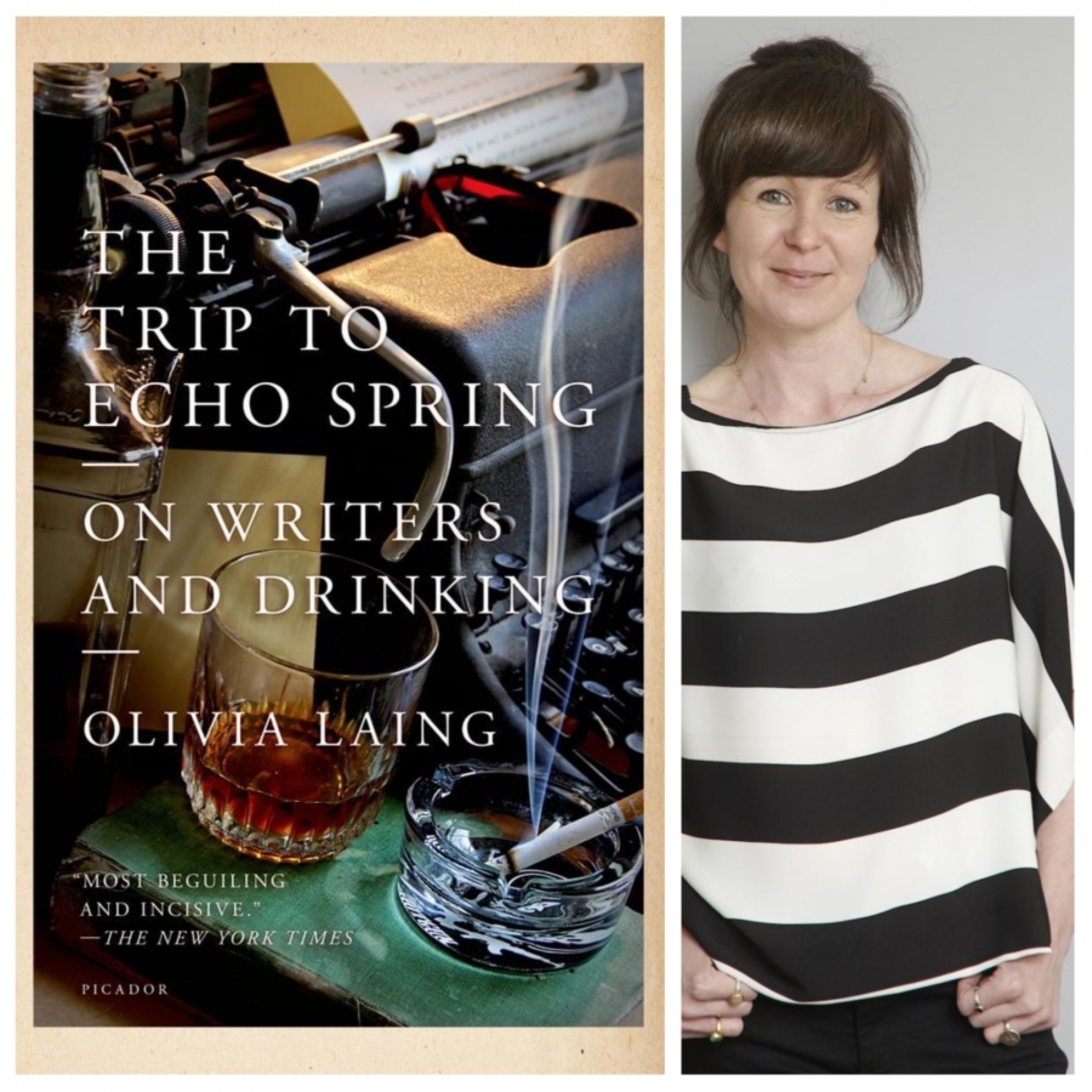

The Trip to Echo Spring, by Olivia Laing

Picador, October 28, 2014

Does liquor inspire and ignite the words of great alcoholic writers? Or do alcoholic scribes produce their work in spite of their addiction? Early in Olivia Laing’s The Trip to Echo Spring, we learn that “four of the six Americans who have won the Nobel Prize for Literature were alcoholics [and] about half of our alcoholic writers eventually killed themselves." This is an epidemic with few boundaries—the list of canonical writers with serious drinking problems cuts across gender, genre, class, race, and time. Could there be something inherent in the writing life—what Georges Simenon called “the vocation of unhappiness”—that drives one to seek refuge in booze?

The Trip to Echo Spring sets out to provide some answers, probing the connection between writing and alcoholism by tracking the sometimes parallel, sometimes intersecting lives of six American writers: F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Tennessee Williams, John Cheever, John Berryman, and Raymond Carver. The book is part biography, part literary analysis, and part travelogue, with the British Laing traversing the U.S. by train to visit her writers’ old haunts and homes. A romantic faith drives her odyssey: She champions the power of great literature to “catch at a deeper and more resonant aspect of alcohol addiction than the socio-genetic explanations that are in currency today,” and she extolls the potential of travel to fuel discovery and insight. “There are some subjects one can’t address at home,” she writes cryptically.

Laing begins her journey in New York at the Hotel Elysée where Tennessee Williams died “unhappy, a little underweight, addicted to drugs and alcohol and paranoid sometimes to the point of delirium.” From this grim opening, she zigzags through the shared childhood traumas, hidden desires, dysfunctional relationships, and maddening bouts of insomnia that united the lives of her writers. She interviews an addiction psychiatrist and regurgitates faddish brain-science—“the limbic system is all greed and appetite and impulse, with the hippocampus adding the siren’s whisper: how sweet it was to remember.” And she digs deeply into her writers’ work (The Trip to Echo Spring is taken from Brick Pollitt’s name for his liquor cabinet in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof). Here, she walks a fine line, mostly successfully, between searching for clues to her writers’ addictions in their fictional characters and avoiding a conflation of made-up stories and real-life biographies.

At its most insightful, Laing’s approach reveals her writers’ alcoholism as an affliction worthy of Greek tragedy. Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Williams, and the others were well aware of one another’s addictions, and they could see the dire consequences of their own drinking. They poured another glass anyway, as if compelled by the Fates. Hemingway boastfully wrote that alcohol “was a straight poison to Scott [Fitzgerald] instead of a food.” Not long after, Hemingway’s own bottles turned toxic. (His doctor-prescribed “low-alcohol diet” consisted of a daily limit of five ounces of whiskey and a glass of wine.) When an addiction counselor told John Cheever that his predicament was similar to that of John Berryman, Cheever protested, “But he was a brilliant poet and an estimable scholar, and I am neither.” The counselor replied, “Yes, but he was also a phony and a drunk, and now he’s dead.” Cheever, in a moment of greater self-awareness, wrote of himself and Fitzgerald, “I am, he was, one of those men who read the grievous accounts of hard-drinking, self-destructive authors, holding a glass of whiskey in our hands, the tears pouring down our cheeks.”

Laing makes a compelling case that these writers affected one another’s lives. But she never makes it clear why a young British woman would undertake a journey to come to grips with the lives and legacies of these six dead American men. As she ventures from the Northeast through the South, Laing reveals that she has a personal connection with alcoholism. Between the ages of eight and eleven, she lived in an alcoholic household, where, one terrifying night, her mother’s girlfriend flew into a violent, drunken rage that ended with police intervention. But that was more than two decades ago, and Laing declines to describe the impact those events or other brushes with addicts and addiction have had on her life since. Instead, she parries any further inquiry with innuendo. That long-ago night of liquor-fueled rage, she writes, has had “long-reaching consequences in the relationships of my adult life.” She elaborates no further.

Perhaps discretion can be a virtue, but in a largely first-person narrative like The Trip to Echo Spring, it hinders our ability to understand Laing as a character, a narrator, and a writer. Why has she come to America? Why is alcoholism a subject she can’t address at home? And what does she hope to find by visiting the former homes of these writers, whose lives and experiences are so unlike her own? They were all alcoholics and Laing saw the ravages of alcoholism as a child. Is that really all? Early on, Laing describes the U.S. as “a country almost entirely unknown to me,” and its foreignness shows. She offers long, florid descriptions of the scenery (New York’s skyscrapers rise “in wavering light like underwater plants”), captures overheard conversations that play to broad stereotypes—a boy is reprimanded for wearing a New York Yankees t-shirt in the South—and jarringly mangles American geography—she thinks the Mississippi Delta is in southern Louisiana and that the Super Bowl is a stadium in New Orleans. Her America is half-formed and her journey through it feels half-told. When Laing visits Raymond Carver’s resting place in Port Angeles, Washington, at the end of the book, she breaks down and cries after reading a graveside guestbook full of testimonials from recovering alcoholics. This is presumably a moment of great catharsis but we’re kept at too great a distance to truly empathize with her tears.

Why do some writers drink? Is there a relationship between addiction and the “vocation of unhappiness”? Can travel help us overcome our native pain? At one point, Laing quotes from the opening of Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls, and then implores us to put ourselves in Papa’s shoes: “Imagine pressing the words, letter by letter into the page. And imagine getting up, closing the door to your study and walking downstairs. What do you do? You go to the liquor cabinet and you pour yourself a shot of the one thing no one can take from you: the nice good lovely gin, the nice good lovely rum.” Yes, you could do that. But many writers have closed the door to their studies, walked downstairs, and enjoyed a cup of coffee, or a cigarette, or a bike ride. What would Laing do? She never tells us, and her reticence not only hinders our ability to understand her, it hinders our ability to understand her writers and their struggle.

Laing has researched the lives of her writers deeply. She quotes telling portions of their private letters and public writing, and pulls important details from their biographies. But she flounders when she tries to make us understand what it might have felt like to be a desperate, disheartened Tennessee Williams or Ernest Hemingway staring at a half-empty bottle of whiskey. The Trip to Echo Spring takes us across America and into six sad, restless, creative, and alcohol-ravaged lives, but its conclusions don’t reach far beyond what Tennessee Williams banally observed:

“Why does a man drink?” the playwright shrugged to Elia Kazan. “1. He’s scared shitless of something. 2. He can’t face the truth about something.”

Enjoy this review? Subscribe to the Oxford American.