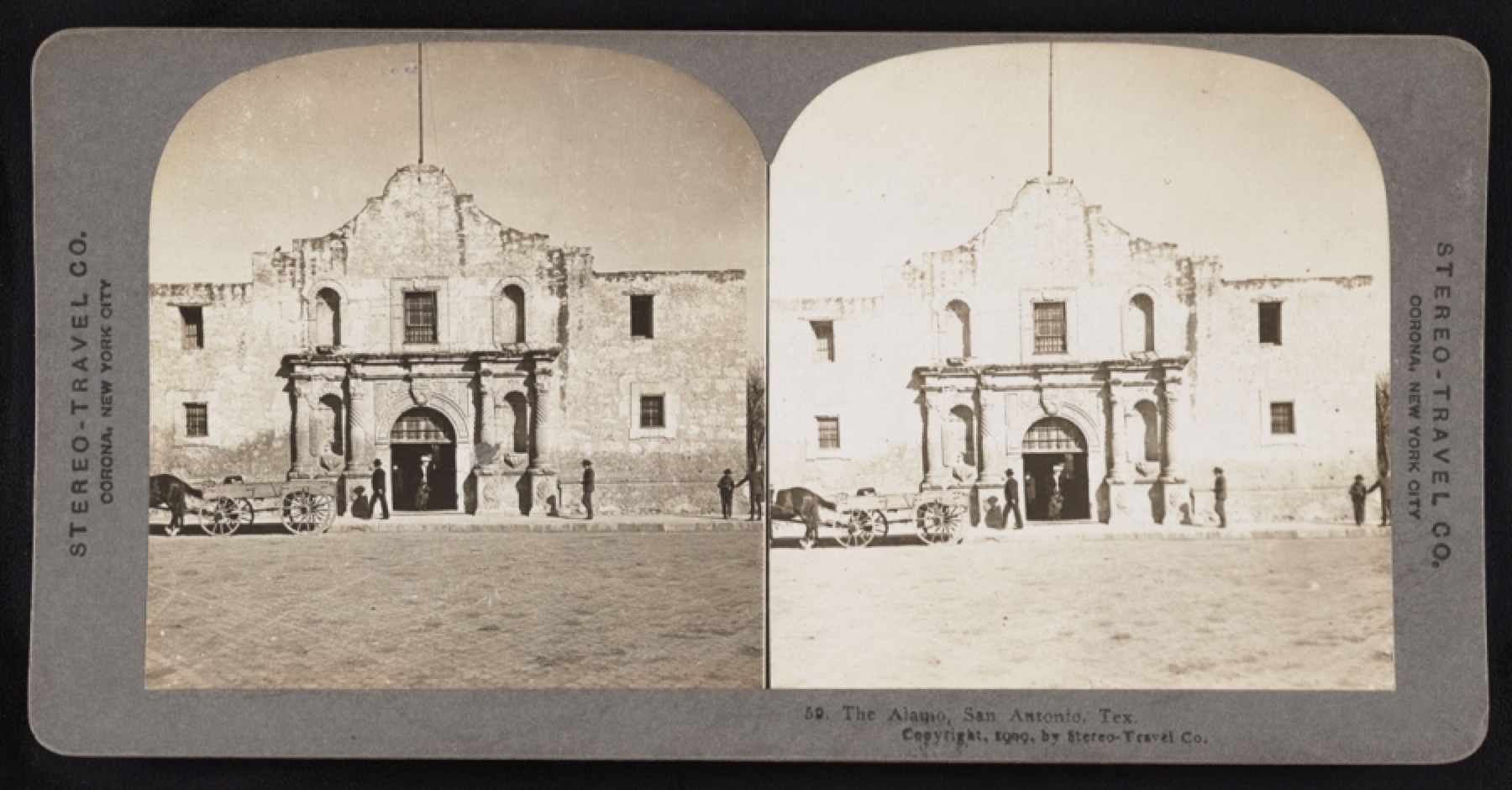

“The Alamo, San Antonio, Tex.,” (1909). From Stereo-Travel Co. Courtesy of Library of Congress

THE WARS LOST AND WON IN TEXAS

By Bárbara Renaud González

The Alma in the Alamo: Stories from San Antonio’s 300th year

Mary Lou Gomez was born on the Westside, one of San Antonio’s oldest barrios, and poorest. And therefore, the historic corazón of Texas history, too. She’s retired now, and as a trained economist, headed one of the city’s finance departments, managing millions of the city’s then two billion dollar budget.

Mary Lou is puro San Antonio. She speaks Spanish and travels regularly into the barrio rescuing abandoned and neglected cats and dogs. (If the city paid attention to her, we wouldn’t have thousands of dogs running the streets, but that’s another story.)

If you saw her, you would think she is a socialite, a member of the city’s upper class. She’s tall, lithe, and fair-skinned. She drives a Prius. It’s only her hair that suggests a Moorish background; I’ve seen women who look just like her in Norway and Poland. In our community, there’s always one pale-face, one güera at the party among the rest of us in shades of brown.

One day Mary Lou and I were at the new library on the Southside with its space-age computers, and Mary Lou decided to see if she could find her family’s immigrant story on genealogy websites like Ancestry.com.

Within an hour she had traced her ancestors back to the tenth century. They were from northern Spain! She was surprised, but I wasn’t. Then, she found her family’s registry papers for Mexico. It was like a cartography of the restless, seeing the ancestral names in Monterrey and then into Texas. Many of the new Spanish-Mexican settlers, including her family, married Canary Islanders who had arrived in Texas too.

Some of this she already knew: Her great-great grandfather was Trinidad Coy, a famous soldier of the Texas Revolution. His father, José Segundo de los Santos Coy, was a soldier at the Presidio San Juan Bautista del Rio Grande del Norte for Spain from 1797 through 1806. In 1808, José Segundo was assigned to a unit that was ordered to protect the border of East Texas against the rumored American invasions from Louisiana. He died some time after 1813. His widow, Maria Luisa Teresa de Rosas, once owned a parcel of land on Commerce Street between St. Mary’s Street and Navarro Street in what is now downtown San Antonio—valuable real estate.

According to the Texas State Historical Association, Trinidad Coy became a mounted volunteer for the Republic of Texas and fought at the Siege of Bexar, actively participating in the Texas struggle for independence. Records show he knew many who died at the Siege of the Alamo. He and his brother Antonio were expert horsemen, sharp shooters, and experienced soldiers, enabling them to serve as scouts and military spies during the Texas Revolution. Trinidad Coy was a compadre of Texas Revolution heroes Captain Placido Olivarri and Captain Juan Seguín, who became the Mayor of San Antonio in 1834, and subsequently a leader of Texan independence.

This ancestor, Trinidad Coy, was in the mounted volunteers who helped protect San Antonio from hostile American Indians, too. Looking back, it seems that Trinidad Coy was faithful to Texas as a Spanish Tejano. During the fallout of the U.S.-Mexican War, he helped his widowed sisters and their children and his brother’s son, Juan Coy. He was also known for helping the starving Polish settlers of Panna Maria during the severe winter of 1856 by providing beef and corn. It is believed that Coy City in Karnes County may be named after Trinidad Coy.

Mary Lou is a fighter like her ancestors. She is a progressive activist who believes in women’s rights, racial equality, and a green environment as passionately as she believes in saving animals. As the youngest of six, she witnessed her father’s alcoholism and early death, and the deaths of two brothers. Her widowed mother sacrificed, as my mother did—by working and working and working, so that Mary Lou could go to college. And now, if you ask her, Mary Lou will patiently explain the injustices of current economic policies on the poor. We both think Mexican-American studies should require a class that examines the economic history of Mexican-Americans.

Because of her story, I’ve seen the way that wars secure land at the cost of great violence, hate, and marginalization. Sometimes the so-called losers win. Like the Alamo that the Mexicans won, whose descendants lost everything. What about the downtown real estate? Mary Lou doesn’t know what happened to it. Apparently, not all heroes die rich.

But the war continues: Poverty, illiteracy, prisons, politics. And the “Anglo winners” may lose their creation myths in the years that follow. Like the Alamo.

The inheritors of this Texas myth have inherited an immigrant story of glorious battles in the name of liberty, which was always about land. My Tejano father believed in this myth too, even though his own mother was likely Lipan Apache, and had lost all of her family in even earlier invasions.

But the Tejana descendants—like Mary Lou and myself with the blood of so many winners and losers—realize we can’t live in the past. We respect, but can’t glorify the ancestors. Democracy is the only land we seek. A land to be shared with everyone.

The wars are over for us. Nobody won, and everyone lost.

“The Alma in the Alamo: Stories from San Antonio’s 300th year” is a part of our weekly story series, The By and By.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.