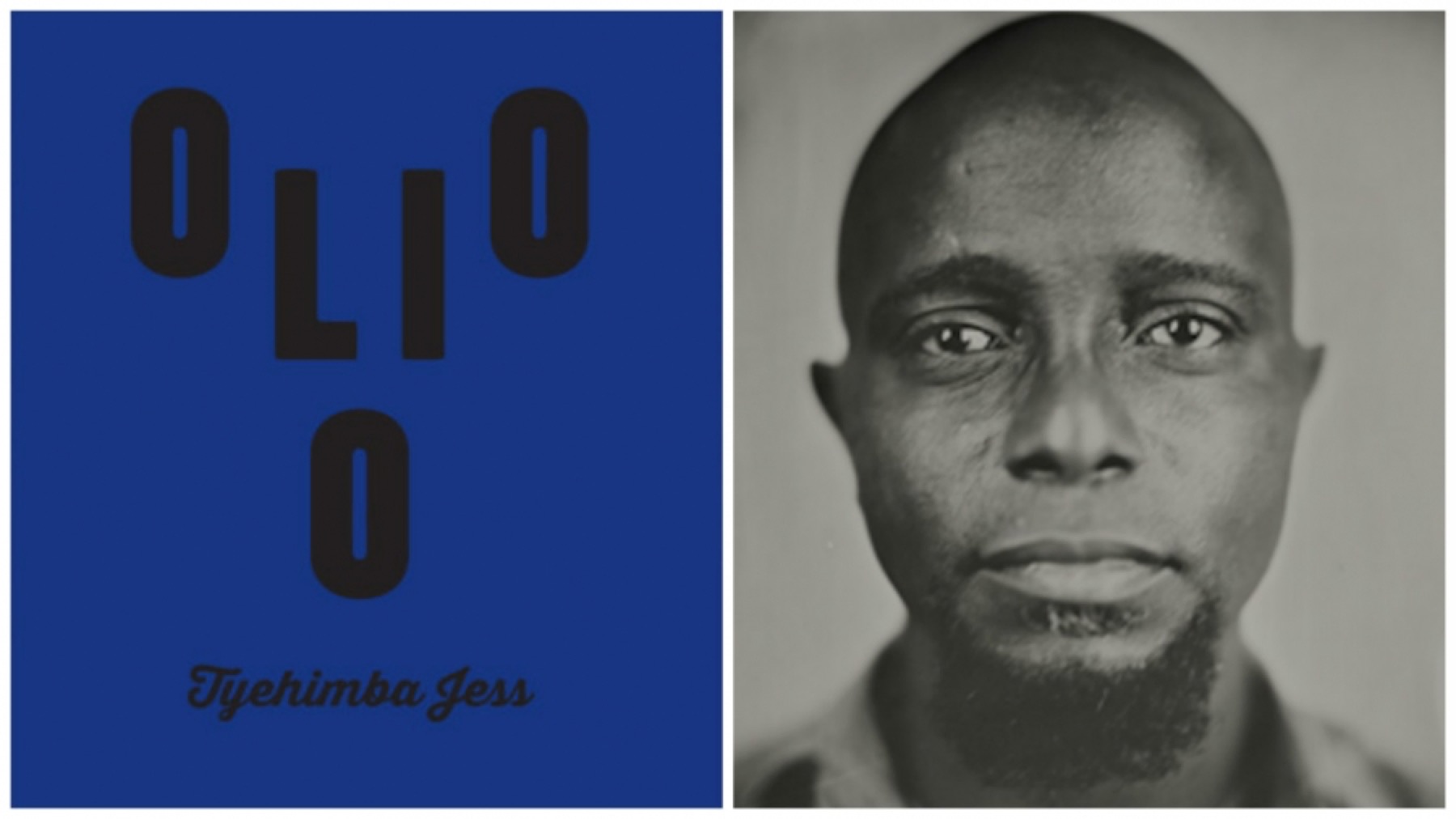

Olio by Tyehimba Jess is out today from Wave Books

THE WORK OF RECLAMATION

By Kaveh Akbar

Olio, by Tyehimba Jess

Wave Books, April 5, 2016

olio /ōlēō/

a: a miscellaneous mixture of heterogeneous elements; hodgepodge

b: a miscellaneous collection (as of literary or musical selections)

also: the second part of a minstrel show which featured a variety of performance acts and later evolved into vaudeville

Publishers Weekly calls it “encyclopedic” and “abundant.” NPR calls it “sprawling.” Nikky Finney calls it an “almanac.” It is obvious at first glance: Olio, out today from Wave Books, is a major American release.

Eleven years have passed since Tyehimba Jess’s first collection, leadbelly, won the National Poetry Series to great attention. That lyric biography of the title’s namesake announced Jess as a significant new voice and introduced his obsessions: music history, narrative collage, and formal innovation—obsessions upon which Olio doubles down. The characters cast in Olio’s poly-vocal swirl count no fewer than a dozen, and almost all of them are famous (or infamous) figures of the early blues or ragtime canon. Performers like Henry “Box” Brown (who “slipped from slavery by mailing himself free to Philly”), Sissieretta Jones (“the first Black Diva to croon in Carnegie”), and “Sent from above” Blind Tom speak and sing—or, to borrow again from Finney, “hymn”—through Olio, their voices braiding together into an astonishing, seamless sound.

eighty-eight mouths. each one sings

hot colors of joy” —from “E♭”

While each of these characters receives ample opportunity to take the stage, Jess is careful to not deliver the reader chaos, using the widely misunderstood story of Scott Joplin as the book’s guiding through line. Joplin—whose work was stolen from him by Irving Berlin and others, who died alone and broke in a sanitarium in 1917—is here given the consideration he desperately lacked in his life. The reader is at once given a celebration of Joplin’s genius and an account of the factors that conspired against it.

Olio is about reclamation, about redeeming what was once stolen. In “Berlin v Joplin: Alexander’s Real Slow Drag,” Joplin snarls back at Irving Berlin: “That thief schemes ‘bout music. He wanted Black gold. . . / snatched from me. He created dark sounds, / his soul corked charcoal, his skin staid white.” In the poem “Sissieretta Jones,” Jones wails: “I sing this life in testimony to tempo rubato, to time stolen body by body by body by body from one passage to another; I sing tremolo to the opus of loss.” Though stolen time is never returned, Olio’s Sissieretta, as with so many of the book’s characters, typifies a timeless music made to outlast the tyranny of culture.

Nowhere in the book does the work of reclamation occur with greater pleasure than when Henry “Box” Brown—who escaped slavery by mailing himself in a box to Philadelphia—appropriates the minstrel voice found in John Berryman’s canonized Dream Songs. Jess takes liberties to actually rewrite these now-cringeworthy moments in Berryman’s opus, telling Brown’s reclaimed story: “Huffy Henry hid the day, / unappeasable Henry sulked” becomes “Our Box Henry hid away. / John Berryman’s Ol’ Henry sulked.” Instead of “I am Henry Pussy-cat! My whiskers fly!”, we get “I am Henry, a free black. My bliss is wry.” With great skill, Jess manages to masterfully echo Berryman’s music while saying something new.

“ain’t nobody going to get nothing back from the past except stories you can wear to put your life straight” —from “Lottie Joplin, Part 2”

It must be said, too, that reading Olio offers a lot of fun. The book itself, designed by Quemadura (the inimitable studio of poet and artist Jeff Clark), rests in the hand like a thick catalog of sheet music. Once opened, the book immediately communicates to its reader what she needs to know: Olio is unlike any other book of poetry you have held. Herein are poems, yes, but also archival photographs; centerfold-style foldout poems, some designed to be torn out and twisted into Moebius strips or rolled into cylinders; adventurous prose; Jessica Lynne Brown’s liberating, original illustrations; fake interviews; and delightfully imaginative appendices.

Of course, these works are also weighted with centuries of atrocity. Of her white oppressors, the sculptor Edmonia Lewis writes: “I mastered / their faith-less hands / beneath the weight / of my mercy-fraught mold.” Of the fever that cost him his eyes, “Blind” Boone sings: “Bless the fever, for it gave me sight; it swole my brain to fit God’s gift.” These moments sing dissonant against the also-present racism of such figures as Mark Twain—creating the dazzling, disturbing friction of a call and response that cannot be ignored. If what Jess has given us is the music catalog for a minstrel show, it is surely set to the buffoonery of received American history, and Olio is its long overdue second act.

Historical personae has long proven to be a useful protest tool against oppression, and is, for this reason, not new to African-American poetry. Olio, though, is so ambitious, so relentless in its pursuit of the antebellum realities that remade our country, with its entrance into the canon we are jolted awake by a hundred alarms, a century’s racket.

“Blind Tom” by Jessica Lynne Brown. An illustration from Olio

“Blind Tom” by Jessica Lynne Brown. An illustration from Olio

Read “General James Bethune and John Bethune Introduce Blind Tom” by Tyehimba Jess from the Spring 2016 issue.