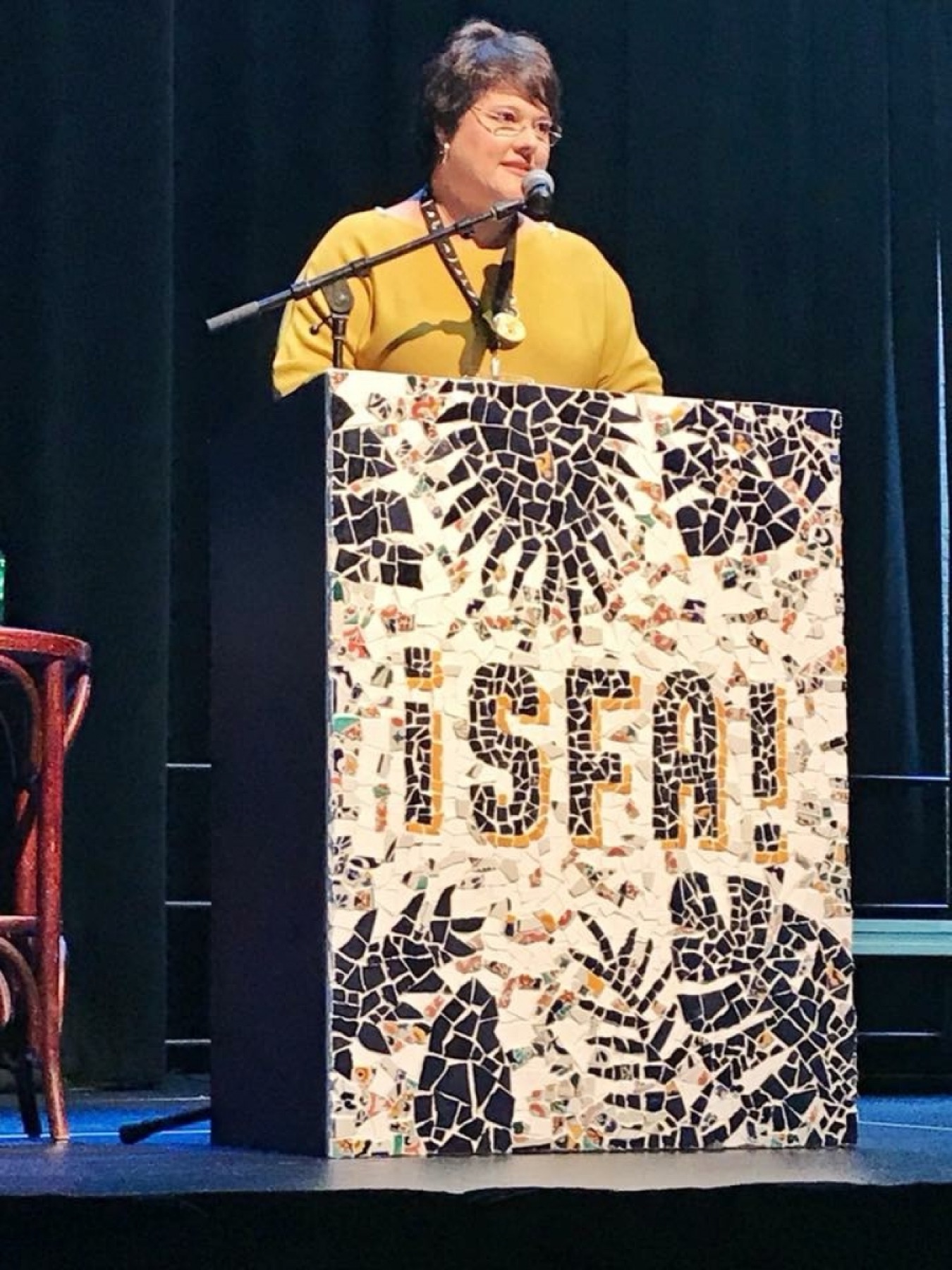

Photo courtesy of Sandra Gutierrez

TO BEGIN WHERE ONE LEFT OFF, AND THEN BEGIN AGAIN

By Sandra Gutierrez

Chronicles from the Nuevo South

My nature is to see the positive in any situation instead of concentrating on the negative, though even I can’t ignore the pessimism that has permeated this past year. At least 2017 is almost over. And I’m glad to report that the state of the Nuevo South is good.

Important conversations are taking place around the Southern table—frank discussions on culinary appropriation and whether anyone can truly claim ownership of an entire cuisine. Southerners and Latinx in both academia and the food writing sphere have continued to expose racism in more than a black-and-white framework, and they exposed the festering wound of sexual harassment in the restaurant industry. I am hopeful that we will no longer feel silenced from discussing openly these painful and important issues.

A few weeks ago in Oxford, Mississippi, the Southern Foodways Alliance celebrated an entire symposium on the Sur Latino. Led by OA columnist John T. Edge, the SFA documents and studies the diversity in the culinary foodways of our beloved South. That an entire symposium was dedicated to exploring the culinary and cultural influences by Latinx in the Nuevo South speaks of an undeniable coming-together of many cooks, writers, influencers, and, yes, eaters of diverse origins in our region.

The weekend was a celebration of Latinx contributions to the Southern tablescape: trailblazing women in the food industry who imparted social change; Southerners who have come to terms with their long-hidden (and self-denied) Latinx roots, forging and finding a sense of place in a South that has resisted rather than welcomed diversity. We all expressed a desire to heal the many injuries that separate us because of our color, heritage, and gender. To say that I left the SFA Symposium injected with optimism is to put it mildly. Good change is happening in the South, which is home to movements for racial healing and political understanding. And of course, food makes these discussions more palatable and less divisive.

A few days ago, I accepted the Grand Prize M.F.K. Fisher Award by Les Dames D’Escoffier International, an organization of women in the food industry, for an essay I wrote for this magazine. I was proud to make the following remarks, and I’d like to share them with you:

Writing and food have always been linked together in my life, ever since I was a little girl growing up in Guatemala City. I don’t remember a time when I didn’t want to be a writer or a time when I didn’t want to eat. It seemed natural to marry both into a career back in 1996, when I began to write about food.

However, it would be years before I realized that food writing has power to move people, to change opinions, to soften disagreements, to become politically active, and to build community.

It was M.F.K. Fisher who said, “Sharing food with another human being is an intimate act that should not be indulged in lightly.”

And she was right. Sharing food at the table is powerful. It’s why people—even those who think diametrically opposite from others—can often communicate. The table is the perfect place to have the “difficult” conversations that often fail when they’re attempted in other settings. Breaking bread together is sacred—thus we must do it often and with people with whom we differ on opinion and talk about racism, injustice, politics, sexual harassment, and other delicate subjects. As long as we do so with respect, with the same benefit of the doubt given to eating someone else’s food without fear of poisoning, and with the prerequisite of agreeing to disagree, the table is the best place to have discourse and to tear down walls.

At a time when being Latina in itself seems to be provocative, being an outspoken one is even more revolutionary. However, it was through food writing that I found my voice. It’s through words that I’m able to be part of a social movement that aims to catapult women of all races towards finally breaking through the many glass ceilings in our world. Instead of fearing other women or competing to see who gets there first, my goal is to use my words as a virtual shoulder for other women to stand on, so that other women can stand on theirs, and so on and so forth. So that each time one of us breaks a glass ceiling—any glass ceiling—we can all say that we played a part in helping her reach it. Because it’s not about who gets there first. It’s about being a part of the movement that helps us all get there.

My hope is that next year we’ll build more tables and we’ll make them all round—with nobody at the head, all of us seated as equals at the repast; that we can continue to entice honest and open discussions in safe spaces where respect is understood, camaraderie invited, ideas encouraged, and diversity (of race, gender, and thought) celebrated—while we all enjoy comforting food.

“Chronicles from the Nuevo South” is a part of our weekly story series, The By and By.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.