To Zion, Marching

By Nadirah Simmons

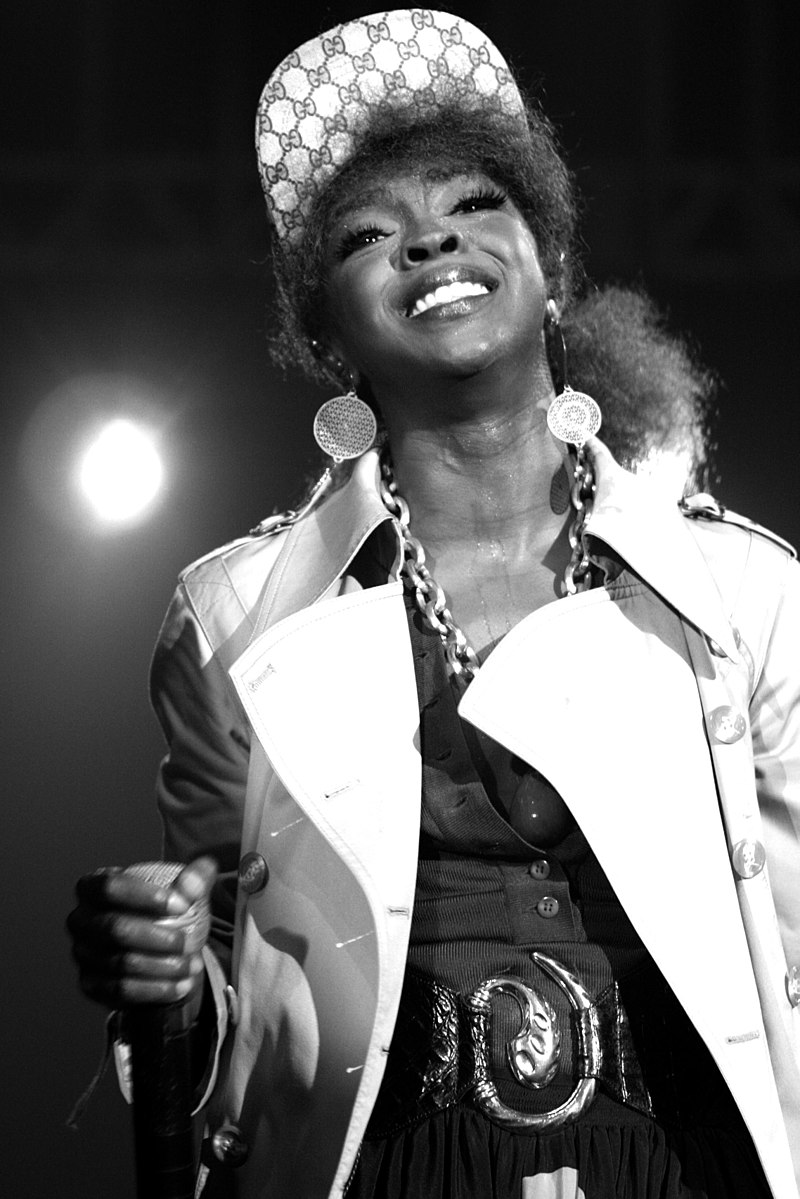

Lauryn Hill at Tom Brasil in Sãn Paulo, Brazil, 2007. Photo by Daigo Oliva, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Zion. A destination. A name. A story. A Lesson. During her pregnancy with her first child, born in 1997, Ms. Lauryn Hill penned “To Zion,” the seminal and arguably most introspective track on The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill that also bore the child’s name. Ushered in by the sounds of Carlos Santana’s guitar, Hill rejoices in the triumph of motherhood while simultaneously lamenting the opinions of those around her. It’s revelatory. It’s expansive. And it’s Hill—singer, songwriter, actress, producer, and architect—at her best: building upon the kind of storytelling and space-making that were hallmarks of blues women of the South, while also pulling sonic influences from across the African diaspora.

The Jersey-bred artist’s departure from the Fugees, the group of which she was a member since her freshman year in high school, carved out the space needed for Hill to create “To Zion.” It wasn’t the first time she took command. She founded her high school’s gospel choir. She led the cheerleading team. At seventeen, she portrayed the recurring role of Kira Johnson on the CBS soap opera As The World Turns. During her senior year of high school, in 1993, she co-starred alongside Whoopi Goldberg in Sister Act 2: Back in the Habit. The following year the Fugees would release Blunted on Reality, their debut album. And while the album earned nowhere near the critical or commercial success of its follow-up, The Score, Hill’s performance was captivating enough for Rolling Stone to suggest that she “leave the guys behind and go solo.” In order for Hill to create a song as personal as “To Zion,” clearance was crucial.

This kind of space-making defined the music of early blues women. In post-slavery America, ring shouts, field hollers, and call and response patterns that previously accompanied the arduous work done in groups on the plantation took on a new form in a genre that was self-conscious and whose lyrics did not center labor. The call and response pattern on Ma Rainey’s “Countin’ the Blues,” recorded in 1924, becomes apparent: when she sings the line, “Lord, restless at Midnight, Jail-House / made me lose my mind,” the cornet, trombone, and clarinet respond to the tune of the beat. In Bessie Smith’s (Rainey’s mentee) “Empty Bed Blues,” trombonist Charlie Green blows his horn as a reply to Smith’s laments for a past lover. Hill’s “To Zion” ends in triumph, with a choir repeating the words “Marching, beautiful, beautiful Zion,” to the beat of a drum. It’s this kind of responsive song structure that contributes to the power of facilitating both thought, conversation, and collective engagement.

The blues is a genre whose performers rely on poetry, drama, and music as the principal modes of expression. To put it simply, blues is an experience. It creates a space through which its artists can understand the world around them. It necessitates presentation for community connection. Songs like Rainey’s “Prove It On Me Blues,” “Black Eye Blues,” and “Jelly Bean Blues” addressed sexuality and queerness, domestic violence, and heartache. Smith sang about similar themes, as well as incarceration and poverty on songs like “Sing Sing Prison Blues” and “Poor Man’s Blues,” respectively. For these Black women blues singers and the artists who followed, love, sex, betrayal, and individuality are an essential part of their music. These messages and collaborative/collective performance styles define Miseducation and “To Zion.”

Hill opens the song singing:

“Unsure of what the balance held

I touched my belly overwhelmed

By what I had been chosen to perform

But then an angel came one day

Told me to kneel down and pray

For unto me a man-child would be born”

The song is a beautiful portrait of young Black motherhood that represents the joy of carrying life in the face of a society that attempts to demonize you at every turn. There’s an insurmountable pressure placed upon Black women to follow traditional notions of domesticity and the “right” path to motherhood that is not just relegated to hip-hop. In Hill’s time the pressure came in the form of things like anti-Black legislation made law by President Clinton. In today’s society the pressure exists online, with social media accounts, podcasts, and blogs alike projecting views on what Black motherhood should be or look like on everyone from a random woman on their timeline to some of the biggest stars. These beliefs assert that we must be successful in our careers and then married before we decide to have children, and that the joys of motherhood and support from one's community should only be reserved for those who follow said path. On “To Zion,” Hill rejects this demand, using her lyrics to affirm her right to pursue motherhood her way. Her message was one that built and supported a community of young Black women who longed to be or already were mothers.

And the message was heard loud and clear, illustrated most evidently by the Black women in music today whose pregnancies defy what society deems acceptable. When Yung Miami from the City Girls announced that she was pregnant with her second child in October of 2020, fans and detractors admonished her, questioning how she would be able to work and hold down the group. Rihanna’s pregnancy announcement came in the midst of a six-year long plea from fans for new music, who declared on social media that they would never get a new album because of the baby on the way. Cardi B’s first child came at what many described as the “height” and “beginning” of her career, with many saying the pregnancy would derail her success. She released a song on her daughter Kulture’s first birthday addressing the same themes as Hill:

“Cardi, you so stupid, you gon' ruin your career

I know I won't, but if I did, I wouldn't care

I started winnin' when the whole world was doubtin' on me

Think I'ma lose when my lil' baby countin' on me?”

Hill gave grace and dignity to women who wanted to work and be mothers. Women who did not see marriage as a prerequisite for parenthood. Women who rejected what was deemed the “right way.”

The legacy of The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill persists across many realms. This album broke the record for first-week sales by a woman artist and made Hill the first hip-hop act to take home the Grammy for Album of the Year in 1999. In 2021 it was certified diamond by the Recording Industry Association of America, making her the first woman rapper to achieve this feat. There’s also the lawsuit, filed in 1998 by a group of musicians known as New Ark (Vada Nobles, Rasheem “Kilo” Pugh, Tejumold Newton, and Johari Newton), who stated that Hill “used their songs and production skills and failed to credit them for their work.” In the suit, they claimed to be the primary songwriters on two tracks, “Nothing Even Matters” and “Everything Is Everything,” and major contributors on six others. In the claim they also asserted that they were owed full or partial production credit on five tracks. In total, New Ark wanted credit for thirteen out of fourteen tracks, or more specifically, all of the tracks except for one: “To Zion.”

Hill remains an architect. She served as the mouthpiece for a generation of Black women. Where blues women used the sounds of horns to respond to their lyrics, Hill used drums. Where blues women used lyrics to create spaces for Black women to be seen and heard through the discussion of revelatory, “taboo” topics, Hill used her words to affirm Black women’s right to choose—or not to choose—motherhood on their own terms, not those shaped by misogynoir or white male hegemony. Hill incorporated the strings of Carlos Santana to create a sound that could be recognized globally and reach Black people across continents. And when you realize how layered the song is, from its nods to blues traditions to lyrics that affirm “the joy” of motherhood, you might never hear “To Zion” the same again.