Up To And Including The Pectoral Fins

By Matthew Neill Null

Redneck Letter from Rome

In the West Virginia of long ago, when it was a place with work that lured people, rather than spitting them out into the world, the Calabrians came to mine the coal, the Sicilians to lay the rails, the Abruzzese to chisel lovely stonework on the railroad tunnels and passes—you can still find that abandoned work in places, overgrown in ivy and filth, the names of its artisans lost to history. It’s not much remarked upon, but Italian immigrants have shaped the culture of West Virginia as much as any other bloodline. Thumb the phonebook and you’ll see Marcozzi and DeNardo alongside the expected German, Anglo-Irish, and Huguenot names. The descendants of Italian immigrants have had a strong (enemies would say outsized) presence in state Democratic Party politics as well as its labor unions.

By the uneven grace of the universe, I’m living this year at the American Academy in Rome, where literary demigods have blessed and burned the ground: Ralph Ellison and Francine du Plessix Gray, Sarah Manguso and Junot Díaz, Miller Williams and Padgett Powell.

In a fluke, just before I got news of my fellowship, my friend Phyllis sent William Demby’s books my way. His novels are out of print, but she, a good citizen, grabs them up when she can. An African-American novelist born in 1922, Demby made the startling jump from a gritty West Virginia coal town to life among bohemian royalty in Rome. Phyllis lives in Clarksburg, one of the state’s heavily Italian towns, where Demby once lived with his family.

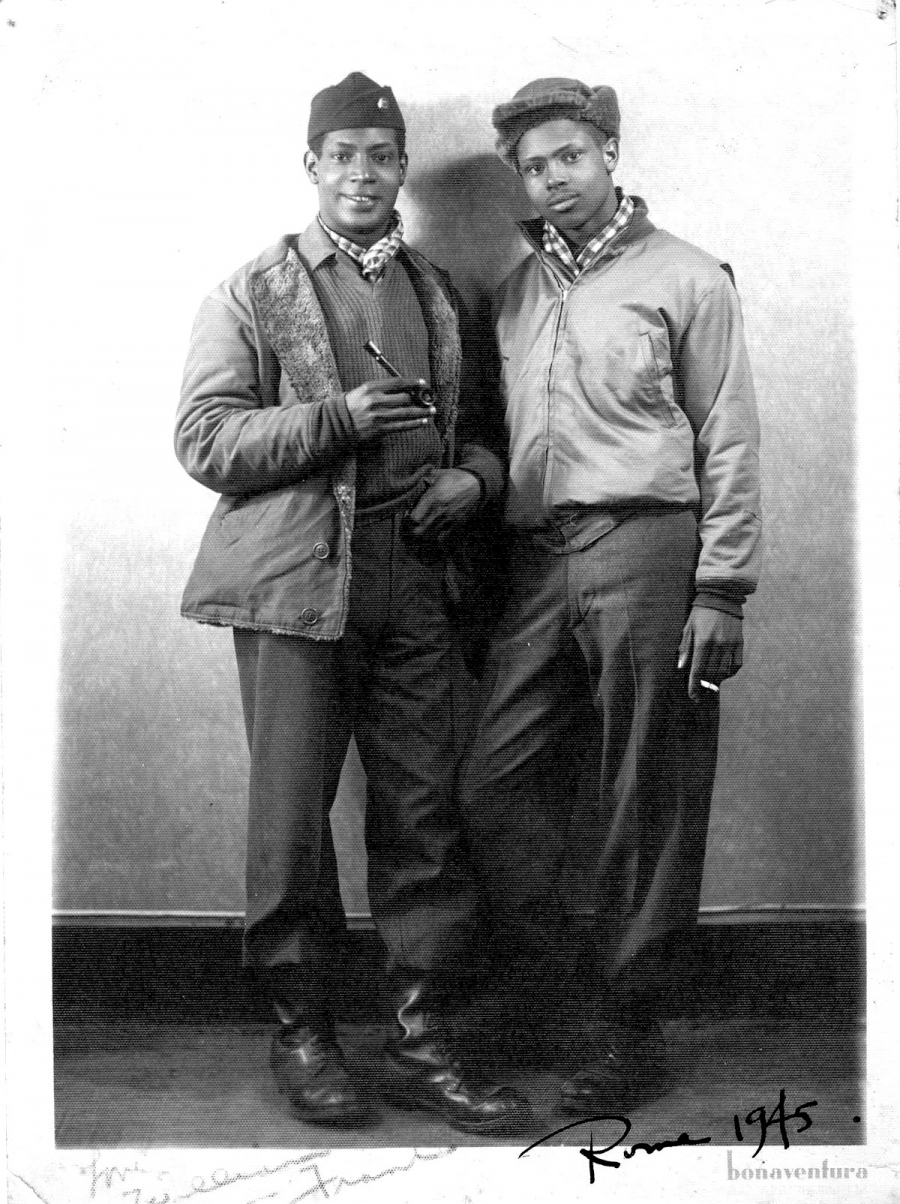

His 1950 debut novel, Beetlecreek, is so entwined with Clarksburg that Phyllis has created a tour of the book’s sites. The story of an African-American boy’s friendship with an aging, white carnival worker—a friendship that neither community is willing to tolerate—Beetlecreek is a strong realist novel, which drew positive reviews and favorable comparisons to Richard Wright upon publication. This is a coming-of-age novel, the one we are all born to write, even if we don’t. But before writing it, a younger Demby first encountered Italy with rifle in hand; he was drafted and took part in the Fifth Army’s invasion of Naples in 1943; like many invaders through history, he took a shine to the place. He remained in Italy through war’s end, returned to the States long enough to earn a degree from Fisk, then moved back to Rome in 1948. He mastered the language, studied painting, played jazz, wrote most of Beetlecreek there, and married the Italian actress and writer Lucia Drudi, creating a bit of a stir. He would live most of his long life in Italy, dividing time between Rome and a Tuscan villa. Their son James still lives outside Florence.

After his celebrated debut, Demby had a fifteen-year silence. Nothing. Well, yes, he was running with the right crowd and wrote perceptive criticism on Italian pop artists such as Francesco Lo Savio, a friend of his. He translated screenplays for Fellini, Antonioni, Bertolucci. He traveled as a journalist to postcolonial Eritrea and interviewed Emperor Selassie, whose subjects had suffered Mussolini’s brutality in a war the world condemned but did nothing to stop.

In 1965, Demby’s second, more-ambitious novel The Catacombs was published; in the United States, it was met with a near-universal bafflement that is hard to understand from the vantage point of 2017. The novel is metafictional, gothic, reality-warping, and rich with a pastiche of headlines in the mode of Dos Passos. It’s not entirely successful, but I can’t help but admire how, like Joyce, like Faulkner, Demby sought to tear down his language and build a new syntax. The character “William Demby” is a black writer in Italy, the nation that cheered as Mussolini nerve-gassed and killed tens of thousands of Ethiopians, yet the Italians he meets are welcoming and fascinated by him—and even more so by his black mistress, the dancer Doris, fetishized by the white men she encounters. She carries a child and is unsure if it belongs to Demby or her other lover The Count, an Italian aristocrat, who keeps her in a vast apartment. Colonialism and its bloody breakup grounds the novel (particularly the Algerian War and the Cuban Missile Crisis) but also brings hope, in the form of a resurgent Africa of self-ruling nations. The novel would appeal to, I think, admirers of Samuel R. Delany and Paul Auster, but it just didn’t find a readership and perhaps never will.

It’s so easy to be forgotten, even when one creates startling work and lives a rich life among the right people. Demby’s novels deserve to be read. He died at Sag Harbor in 2013. On a happy note, Demby’s son tells me that Ishmael Reed is soon to publish his father’s final novel King Comus, never before available to readers.

Bertolucci, Antonioni, Fellini. I have to admit I don’t run in company like that. I like to go down to the Tiber and watch the gypsies drink beer and fish for whatever anemic bounty the river will offer them—I’ve tried to talk to the gypsies in my cracked Italian, but wary of strangers, understandably so, they keep to themselves. Like people back home, the gypsies use long rods baited with cheese and squirming mealworms. I’ve seen precisely one flappy perch pulled from the Tiber, but hey, it’s a good excuse to get away from home and drink some beer. The Tiber is not an enticing waterway, not in urban Rome, anyhow. After a good rain, near the ancient island where the Temple of Aesculapius stood with its healing serpents, the rapids swirl with a thousand plastic bottles. The bacteria count is high, the Cloaca Maxima still delivers the city’s filth, and yet there was once an incredible eel fishery here, even into the 1960s. I think of the last eels, wriggling their way from the Sargasso, through the straits of Gibraltar, past the purse seines and tuna-thrash of the Mediterranean, nosing right up to the palace intrigues of the Vatican (“at least all of Pope Francis’s enemies are in one place,” a Roman acquaintance tells me, “that’s why he prefers to stay at that monastery”), to the banks of the river where our myth was born, just as they did in times of caesar and plague.

Rome has been estranged from its river since 1876, when, tired of seasonal floods, the city-planners built high stone embankments to protect neighborhoods like Trastevere. Few wander alongside the river as they do on the Seine. This is a bit startling, in a place crowded with tourists. Beyond a few cyclists, the riverbanks and the graffiti-coated embankments have been ceded to the desperate: the homeless, the gypsies.

Yet Rome was known for its fisheries, for the fish market that would become the Jewish Ghetto. An inscribed marble-slab from 1581 remains near the Church of Sant’Angelo in Pescheria, reminding fishmongers that they must give up the heads (up to and including the pectoral fins) of large fish to the city administrators. The government, just or unjust, always wants its cut. The heads of the “Tiber Wolf,” Lupus Tiberinus, a large sturgeon, were prized for soup, and the much-loathed tax stood until 1798. Rome has always been a city of sustenance, where food is all. At the Musei Capitolini, one can see a stone sturgeon, a “regulum,” against which the mongers were to measure their catch. A ghost of what was. Sturgeon have been absent from most Italian waters for decades, done in by postwar dam-building, pollution, and lax regulation.

And yet, as long as a handful of eels still venture up the Tiber, Rome is connected to that old dream of seasonal wealth, of drawing sustenance from water, of a few dozen people leaving their barricaded hills, settling the lowland rivers, and trying to find a way to live together and multiply. It’s hard to live with other people. It’s impossible. At the Uffizi, I gazed at Ligozzi’s The Allegory of Virtue, Love Defending Virtue against Ignorance and Prejudice, which is precisely what most political movements imagine themselves to be. From afar I watched the bizarre election in my own country, as Demby watched the assassination of JFK and the brutality in Algeria; it is so easy, so intoxicating, to leave your land: a radical simplification. But I’m inclined to return, go down with the ship.

I watched the marchers here in Rome, chanting against their constitutional referendum. I didn’t have to care about Matteo Renzi’s questionable reforms, I could merely follow. All becomes as dream. And two ideas tore at each other. Yeats said, “Rhetoric is the language of argument with others, but poetry is the language of argument with ourselves.” Of course poetry is preferable. Eugenio Montale, that master of equivocation, wrote in Ossi di seppia,

É l’ora che si salva solo la barca in panna.

(“And this is the hour when only the grounded boat will be saved.”)

Why not stay? The urge to drag yourself onto the beach and wait out the storm is strong, to wait it out like the cagey peasant you are, unwilling to commit, in a land as fatalistic as your own.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American and read more from The By and By.