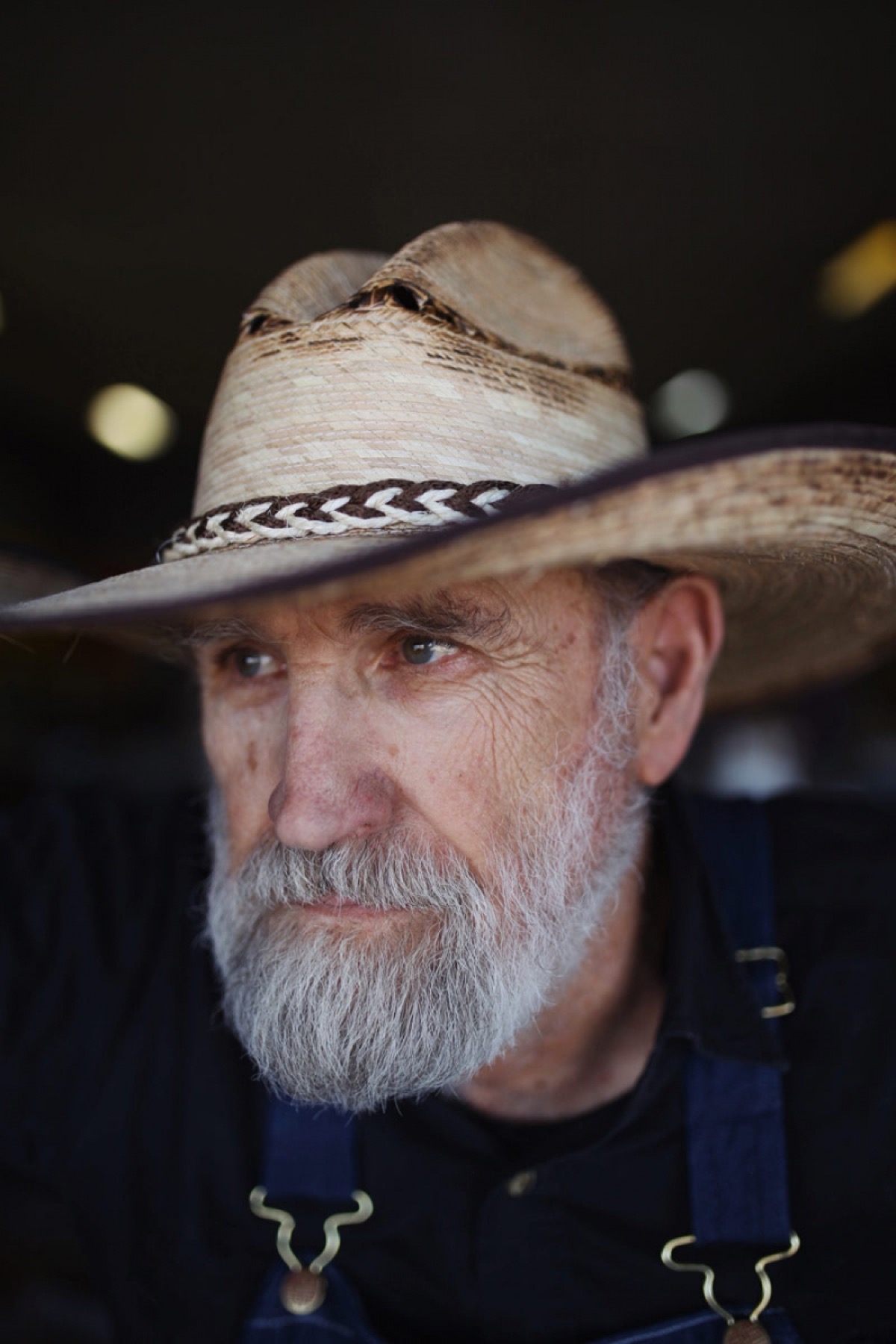

buZ blurr in the doorway of his Front Street studio. Downtown Gurdon, Arkansas. March 19, 2019. Photos by Matt White

WAIT OF WORLD

By Matt White & Matthew Thompson

“Admittedly the words were derived from isolation, a chance at transcendence.”

Born Russell Butler in Lafe, Arkansas, in 1943, buZ blurr is the pseudonym assumed by the enigmatic artist and third-generation, forty-one-year career railroad man. Rooted in the folk art tradition of hobos and rail workers, blurr’s iconic Colossus of Roads drawing of a pipe-smoking cowboy in transit—each iteration elevated by an esoterically poetic caption in language drawn from his daily life—has adorned tens of thousands of railcars across North America. Drawn in obscurity for decades, blurr’s ultimate outing as its creator (in the 2005 documentary Who is Bozo Texino?) solidified his position as a beloved hero of an outsider underground.

Living and working in Gurdon, a small Clark County, Arkansas, railroad town, blurr is a prodigious writer, photographer, bookmaker, and a giant of the modern Mail Art movement. Imbued with mystery at seventy-five, blurr’s astonishing spectrum of work continues to smash through the walls of geographic, cultural, and personal isolation. We spoke with the artist on the eve of his upcoming gallery show in downtown Little Rock, an extensive survey of self-portraiture spanning nearly forty years.

Your artistic output has predominantly thrived along the vast networks of the railroad and postal systems, via train and Mail Art. Is this directly correlated with living in rural Arkansas, and perhaps, a yearning to let your audience—American and otherwise—know that you exist?

Although my father and his father were railroad men, my maternal grandmother's father was a newspaperman who published weekly in three different cities in northeast Arkansas: at Gainesville, Rector, and Paragould. He learned the printer’s trade by apprenticing with Mark Twain on his brother Orion Clemens’ Hannibal, Missouri, newspaper prior to the Civil War. Thus I claim this as an atavistic trait for my affinity for print. As Marshall McLuhan said in Understanding Media, “with Xerox, every man a publisher.” Cheap and easy electrostatics allowed me to plug into the Mail Art network of like-minded people. As a subscriber of Rolling Stone magazine, I read about Correspondence Art in two consecutive issues in April 1972. Around this time, I mustered the courage to begin my boxcar icon dispatch, November 11, 1971.

You underlined the words “Extreme Cultural Isolation” in a previous interview. What has been the impact of Gurdon, Arkansas, upon your work?

Apropos that quote, in response to an engineer’s inquiry as to who was the subject of a stencil sprayed on a boxcar, I replied, “The world’s most famous brakeman, Jack Kerouac.” “Naw,” he said, “Never heard of him. Jimmie Rodgers, The Singing Brakeman, was the most famous.” “Touché,” I said. “Huh?,” he said. “Nevermind,” I said, realizing the train caption for the day.

On a caboose between Prescott and Gurdon, Arkansas (1984). Photo by Rex Potter, courtesy of buZ blurr

One thing that stands out about Gurdon is the wild cacophony of sound emanating from downtown. What might one might hear standing outside your studio on Front Street?

For sure, there’s the noise of passing trains, the jake brakes of logging trucks trying to avoid crashing through the crossing gates, the organ music piping from the Presbyterian church.

Can you give us some insight into the work and concept of your upcoming gallery show?

In line with the title of the exhibit—“Wait of World: buZ blurr Age Progression” the primary focus will be photographic works annually documenting the rapid parade of birthdays. Additional pieces from various gatherings of hobos and Correspondence Art Congresses will be interspersed in the same graphic stencil technique as the self-portrait black-and-white birthday progressions.

Do you consider the impermanence of life to be the connecting theme of your work across multiple mediums?

Indeed, despite abundant postulations of afterlife rewards or condemnation, every cognate person realizes the physical body is finite. “Wait of World” addresses the ultimate demise, be it sudden or prolonged agony. As Kafka said, “The meaning of life is that it ends.”

Are your age-progression pieces inspired by artist Guglielmo Achille Cavellini’s autostoricizzazione (self-historicization) concept? What is your interpretation of this idea?

Cavellini’s basic premise is each person’s life is unique, and one only needs to document their story to confirm his concept, for which he should be praised and credited. He foresaw there would be celebrations of his genius at the centennial of his birth year of 1914. Although Cavellini died in 1990, there were exhibits all around the world honoring him in 2014.

What compels your obsession with the passage of time?

“All photographs are Memento Mori.” —Susan Sontag. i.e. “Gather ye rosebuds while you may.”

Did you envision the possibility of this exhibit decades ago?

I’ve had a lot of work framed over the years for the purpose of exhibits planned upon retirement from my main railroad career, including one in New York’s Chelsea art district at International Curatorial Space. That exhibit was entitled “Pretty Ugly White Black Blues Again,” a reference to the graphic nature of the up-close, distorted portraiture not always appreciated by the subjects of stenciling from Polaroid negatives, as intended for stamp sheet documentation. Subsequently these works were exhibited in Springdale and Hot Springs, Arkansas. After all the intervening years, this exhibit has been a surprise.

As a high schooler in Earle, Arkansas, did you have any awareness of the town’s great painter, Carroll Cloar? Did you find any inspiration from his surreal views of the South?

I attended my freshman year at Earle High School and was a member of the football team, the Bullpups, being the diminutive of Earle Bulldogs. The painting by Carroll entitled My Father was Big as a Tree was reproduced in an art periodical I perused at a library in Palestine, Texas, the following year. So I was aware of his work long before knowing he was a native of Earle. It was great to see the west side of Earle High School in his painting of the first football team in “The Crossroads of Memory: Carroll Cloar and The American South” exhibit at The Arkansas Arts Center. Great rendering of the Missouri Pacific train depot in pencil and paint. Certainly his light and subject matter were surreal. Tav Falco and Randall Lyon interviewed him in their video “Televista Projects of Memphis notables and Mississippi bluesmen” now in the collection of WPA Film Library, MPI Media Group, Oak Park, Illinois.

Can you speak a bit on your long relationship with and draw to cameras? What do you love about photography?

I was exposed to and fascinated by the photography of my large fraternal and maternal families. I would look through the cardboard boxes when we visited my grandparents and see the Kodak pictures mailed home as members of the family dispersed in their various lives. We didn’t seem to be able to afford a camera.

You are sitting on an extensive archive of your own beautiful color photography. Can you envision a broader appreciation for this work at some point in the future?

Figure I’ll have to publish them in my own bookworks.

You have coined your practice of creating stencils from Polaroid photographs and then to stamps as “Caustic Jelly Post.” What is this process?

My fascination with the immediacy of instant photography, weighed against a futile ambition of a darkroom and SLR camera, afforded the purchase of a black and white Polaroid with Dr. Land’s magic emulsions that transferred the negative image. The image was exposed through the lens to the print when pulled through the rollers. This necessitated a product liability warning to discard the negative for the developing fluids—or their term, Caustic Jelly—which could cause alkaline burns and other injuries. As an image junkie I retained them to dry and experimented with cutting silhouettes and eventually opposite stenciling with an exacto knife that revealed a positive image when turned over, since the back was black. Then you could slap them on a photocopier for reduction to stamp size to be composed for an edition of Caustic Jelly Post in my philatelic portraiture.

What circumstances led you to attend the opening of William Eggleston’s infamous color photography exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in 1976?

Tav Falco—being a friend of William Eggleston and using Eggleston’s darkroom to print his own B&W pictures—was invited to the private preview of the exhibit at MoMA, along with a guest. Since I had been to New York in June 1973, he invited me to accompany him. So I drove to Memphis and we flew to Kennedy and shared a cab with others into Manhattan.

Do you feel a connection between your train art and the blues?

Indeed it was my own sing-song blues, “The Dragging, Kicking and Shoving Blues.” A commitment to my necessary livelihood to provide for a family, yet still entertaining the conceit of being an artist.

Can you give us some insight into the iconic footage of you featured in Bill Daniel’s documentary, Who Is Bozo Texino? What do you remember about that day?

In 1991, Bill Daniel began his hobo film adventure and was interrupted by our railroad union going on strike. This was in hopes of a decent raise after two contract periods under Reagan and Bush had promised a “kinder, gentler” administration, which was another fucking lie. Congress put us back to work under Presidential Emergency Board arbitration, which gave us another paltry raise, but stripped us of a lot of our work rules contracts that more than made up for it. Supposedly the three judges were made up of a union representative, a railroad rep, and a neutral party to negotiate—would you guess he was a friend of Bush? Anyway, I picked Bill up in Texarkana and drove back to Surrealville, where he did the filming that outed me as a graffiti culprit and then continued his journey by Greyhound.

The personal letter feels like a particularly fine form for your writing. Several beauties are featured in your book, hoohoohobosfortuitouslogos.

I used to type letters on an Underwood with CMC key punch cards used to run train consists at the depot, and in abundance. The writing had to be concise to fit the small format. A lot of those are in the Smithsonian Institute’s “Archive of American Art” collection of John Held Jr.’s correspondence. With the aid of my son, I finally got a computer in 2000. Boog Highberger, former Mayor of Lawrence, Kansas, observed, “You leapt into the twentieth century now that it’s over.” Subsequently, I’ve preserved some correspondence in the machine.

What were early inspirations which led to a desire to write?

My fifth grade teacher read to the class Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in installments after lunch.

A clear disdain for authoritarianism pulsates through aspects of your writing and art. You’ve witnessed a lot of history over seventy-five years. Are you surprised by the state of American leadership in 2019?

In the divisive split of the current appalling situation, it is wise advice to never discuss politics or religion, especially if your opinions are in the minority in this hostile red state.

Any closing words?

Like Captain Queeg in The Caine Mutiny, I am glad to have zen meditation balls to roll around in my palm to thwart the anxiety over the coming exhibit.

“Wait of World: buZ blurr—Age Progression” is on view at The Bookstore at Library Square in Little Rock from April 12 through May 2, 2019; opening reception with artist in attendance from 5-8 pm on Friday, April 12.

Enjoy this interview? Subscribe to the Oxford American.