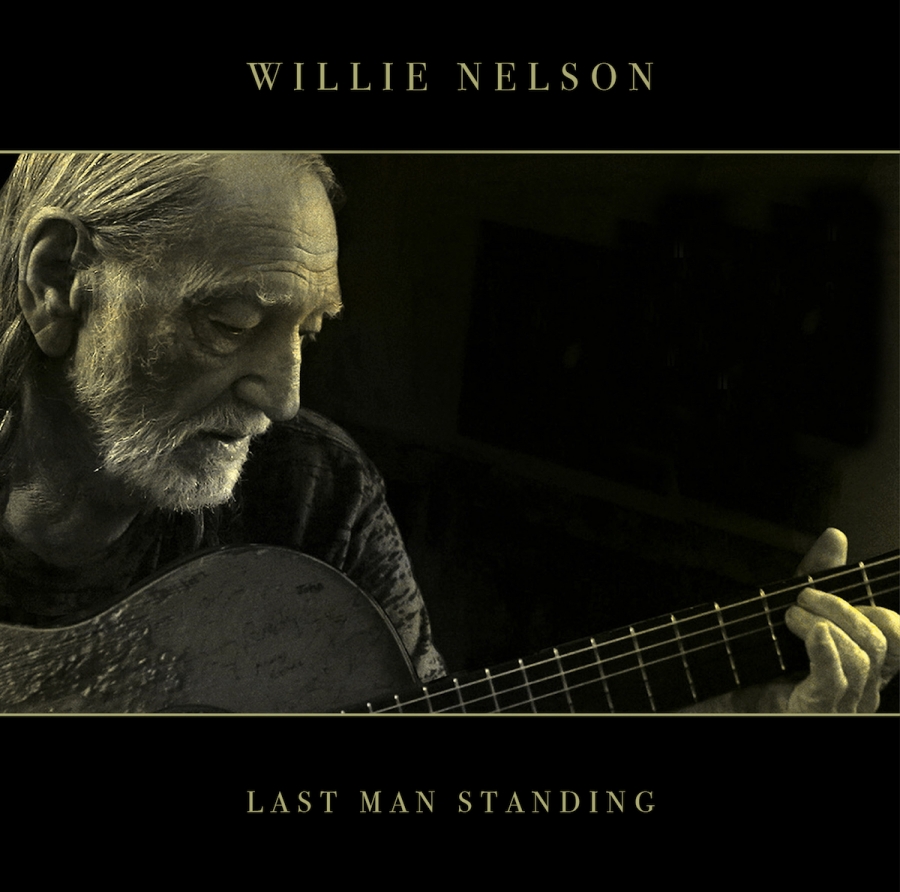

Willie Nelson: Last Man Standing

Willie Nelson doesn’t want to be the last man standing, he declares on the title track of this new album, comprising songs co-written with producer Buddy Cannon. After a moment’s consideration, he adds: “On second thought, maybe I do.”

The song is a wry concession to an overshadowing truth that accompanies Willie Nelson and his music every step at this stage of his life: He’s an 84-year-old man who is one of America’s most preternaturally active and creative artists, and he keeps on going. He still performs something like one hundred shows per year, and records and releases an average of two top-rate albums per year. Nelson’s perseverance is not only extraordinary but heartening. Perhaps no other American artist unifies so many disparate listeners across a troubled land in this time. Willie Nelson doesn’t preach or chide; he doesn’t even claim the wisdom of his years as an exemplar for us all. He does something rather different that digs deeper: He demonstrates that every new season, every new night, offers a way forward with fresh promises — maybe joyous, maybe hurtful — until the end. We live until we die — you, me, Willie Nelson, everybody — and will go through loving and harsh realities that don’t hesitate. That path is inexorable. Last Man Standing is full of both lively beauty and hard truth, but it also offers grace notes. “There’s hope in the new album,” says Buddy Cannon. “Hope and inspiration and reality.”

With its understanding of life as something that is both evanescent and reverberant, Last Man Standing picks up in the territory where last year’s God’s Problem Child left off: The closing song, “He Won’t Ever Be Gone,” was a tribute to a fallen friend, Merle Haggard. This time the line of commemorations has grown. In the opening track, “Last Man Standing,” Nelson sings: “It’s getting hard to watch my pals check out/It cuts like a wore out knife/One thing I’ve learned about running the road/Is forever don’t apply to life/Waylon and Ray and Merle and ol’ Norro/Lived just as fast as me/I’ve still got a lot of good friends left/And I wonder who the next will be.”

Despite that rumination, the song doesn’t feel like a requiem: The music works in an entirely different mood and direction, kicking off like a stampede of race horses, headed for a rendezvous at the liveliest honky-tonk in town. The singer says he doesn’t want to be the last survivor among his allies, then thinks twice. The truth is, he’s in no hurry; he’s well occupied with the here and now: “Go on in front if you’re in such a hurry,” he offers, “Like Heaven ain’t waitin’ for you.”

Willie Nelson and Buddy Cannon first connected in 2008 and since that time, Cannon has been Nelson’s main producer. During the making of 2012’s Heroes they began collaborating on songs and Last Man Standing is made up solely of their collaborations. But there’s a twist in their camaraderie: “The odd thing,” Cannon says, “is we never sit in a room together to write. Never have. We start with our lyrics, and he will text me. He’ll text me a verse and a chorus and we just bounce it back and forth.” On Last Man Standing, Nelson and Cannon’s unorthodox stratagem yielded eleven original songs.

The song “Something You Get Through” is at the heart of Last Man Standing and for that matter, at the heart of Nelson’s years of music and meaning. It’s a song about the devastation we feel at the loss of another and are told we’ll get over it — but we know better. Buddy Cannon relates the story of the moment the song was born. “I was down in Austin for one of Willie’s New Year’s Eve shows. I was sitting on the bus, before the show. There was this lady, who I did not know, who came on the bus and it was obvious that she was very close friends with Willie… I wasn’t eavesdropping, but I could hear what they were saying to each other. She had obviously lost someone very recently and she was talking to Willie about it. I heard the woman say, ‘I don’t think I’ll ever get over this.’ And Willie looked at her and he said: ‘It’s not something you get over, but it’s something you’ll get through.’ That just stuck in my brain. I tried but I couldn’t get that thought out of my head for two or three years. I knew there was a song in there.”

If God’s Problem Child was about mortality, Last Man Standing is largely about life — that is, how we endure it, when to persist. That also comes across in the music: It’s largely an inviting romp — two-steps here and there. The lesson of “Something You Get Through” swings — literally, as in Western Swing — into “Ready to Roar,” a workingman’s celebration of a weekend of dancing, drinking, smoking weed, getting arrested, and getting out of jail to go back for more. The hard-waltz “Bad Breath” is the creed of an indefatigable alcoholic; he knows others might recoil from him, but he also knows this: “Don’t think ill of me if my breath melts the wall/’Cause bad breath is better than no breath at all.”

These are classic country themes and sounds we’ve known since the days of Hank Williams — pairing dance music to portrayals of hurt, because dancing despite agony is another way to get through things. At the same time, the new songs’ age-old veracity is also infused with tomorrow’s regrets. Willie Nelson has now turned out two latter day masterpieces — God’s Problem Child and Last Man Standing in a year’s span. Apparently, he and Cannon are well on their way to making it a trilogy, or quartet, maybe more. “Just think of this as the second page of a book,” says Cannon. Willie never stops turning the pages.

To listen to or order Last Man Standing click here.