Leo Fernandez & the Hot Tamales playing at Kitchens Grocery in 1976. Photograph courtesy of Patty and Bruce MacLeish

YOURS FOR THE CARTERS

By Jennifer Joy Jameson

I’ve always been drawn to collectors, to people who carefully select or enthusiastically gather things others might toss aside. A deeply occupied space often has a story to tell, and sometimes, more is more. In the small, agricultural community of Drake, Kentucky—between Bowling Green and Nashville, about a half-hour north of the Tennessee border—is a small country store called Drake Vintage Music and Curios, and its proprietor, a man named Freeman Kitchens, is the most singular collector I’ve ever encountered. His specialty then and now is the founding act in popular country music: the Carter Family. At one point, Freeman Kitchens had collected every sound recording, television clip, and radio broadcast ever produced by the Carters, and stored them in his unassuming outpost in Drake, organized according to ever-changing criteria known only to him. He founded the Carter Family Fan Clubaround 1950 and served as its president for more than thirty years.

When I first learned of Mr. Kitchens several years ago, I called him up to see if I could sit with him and ask some questions. I wasn’t sure exactly what I was going to use the interview for at that point; I just wanted an excuse to hear his story. Freeman was shy on the phone and convinced that a visit with him would not be worth my time. He told me it had been a long while since anyone had come to interview him. When he finally agreed to a time and date for us to meet at his store, he simply said, “Alright,” and hung up. I’ve known Freeman for several years now, and he’s never uttered a single “Goodbye” before ending a phone call.

While preparing for the interview, I realized information on Kitchens is sparse. There is one photo of him floating around on the Internet, from someone who visited Drake Vintage in 2006. Kitchens is pictured reading a magazine in a blue La-Z-Boy, surrounded by towering stacks of vinyl LPs, household knick-knacks for sale, and framed press shots of country and western musicians from the mid-Fifties.

I had a professor at the time whom I knew would be a good source—in the midst of her lectures, she would sometimes break into anecdotes, like the time a flirtatious Alan Lomax chased her around the Library of Congress when she was just out of college (she had a job there transferring field recordings on wax cylinders to reel tapes). Or the one where she was hired to accompany Son House on a tour to help keep him from drinking. Freeman Kitchens down in Drake? She knew the place well. She and her Jimmie Rodgers biographer–husband had spent many hours in the annex at Freeman’s shop, stacked with 78-rpm records from floor to ceiling on all sides of the room.

She pointed me to a two-page article by folklorist Barbara Taylor published in a 1977 issue of the small regional journal called the Kentucky Folklore Record, the only piece I could find on Mr. Kitchens. “Folksong collection in the United States probably owes as much to the pure enthusiast as to any other group,” Taylor quoted folksong scholar D. K. Wilgus, one of the earliest academics to rally for the scholarly value of “hillbilly” music. “Behind the achievements of the academic tradition, lie the labors of the inadequately known individuals who have devoted themselves to collecting [songs] or paving the way for collectors.”

Freeman Kitchens outside of his shop. Photograph by Jennifer Joy Jameson

Freeman Kitchens outside of his shop. Photograph by Jennifer Joy Jameson

Drake Vintage Music and Curios is a white, wood-paneled addition to the one-story brick home on Plano Road where Freeman resides. When I pulled up, the front of the shop was decorated with seasonal yard art, the doors flanked with a pair of vinyl records and speakers for Mr. Kitchens’s AM radio. The shop is one of just a few gathering spaces in Drake, including the off-and-on Drake Country Store next door, Freeman’s original location. Across Plano Road stand White’s Methodist Chapel and its accompanying cemetery, where most of Freeman’s family are laid, save a few nieces who still live nearby.

When I knocked on the door, a reserved Freeman Kitchens greeted me, and gave me a quick walking tour of his shop. Over the years it has turned into a sort of homemade museum to the Carter and Cash dynasties. Every inch of wall space is covered with framed collages of letters and pictures of the family, including A.P., June, and Anita, Freeman’s favorite Carter. (“She sings better than any of them,” he says.) One wall is dedicated to signed headshots of country artists and variety-show personalities from the Thirties through the Nineties—many of them inscribed to Mr. Kitchens. There are personal photos of the Carters at home, oftentimes supplied to fans by the Carters themselves. And among my favorite pieces of fan-made art on display is an LP-sized painting of the Carters in their famous Bristol Sessions pose, but this time situated in Drake, with Freeman painted in, standing alongside A.P., Sara, and Maybelle as if he’d always been a part of the group.

Freeman first heard the original Carter Family when he was a child listening to their Texas-Mexico border broadcasts on XET. The Carters, and later the Carter Sisters (a “second generation” version of the family band consisting of Mother Maybelle and her daughters June, Helen, and Anita), were always at the top of Mr. Kitchens’s list, but he loved all varieties of hillbilly music and some blues and jazz, as well. “When I was in grade school I started collecting old Carter Family records, and I got to collecting theirs and ended up collecting everybody else’s, too.”

In 1946, when he was twenty years old, Freeman started working for the country store in Drake, C. M. Duncan & Son. The owners began letting him sell his growing collection of 78s in the back, and about five years later, Freeman was able to purchase the store and reopen it as Kitchens’ Grocery, where he sold sandwiches, newspapers, cigarettes, and other sundries, like records. C. M. Duncan also passed to Freeman the duty of Drake community postmaster—a position he held in various capacities for nearly seventy years, until 2013, when the Postal Service no longer saw a need for a Drake P.O.

“I started the Fan Club to help along my collection,” Freeman told me. “Some of the Carter Family records were hard to find, so I wrote to A. P. Carter and asked him about starting a fan club. He answered me on his typewriter and wanted to know what would be in it for him.” Freeman laughed. “He thought it’d be a money-making deal!” Freeman also corresponded with Frances Lyell, a young Nashville musician who sang with the Carter Sisters when one of them was unavailable to tour or perform. Facilitating a direct link to the Carters themselves, Frances helped bolster the official fan club.

While many artist fan clubs of that era were established at the behest of the artists’ record companies, functioning more as a marketing effort than a natural display of fan culture, the Carter Family Fan Club was always organized by the fans and, at times, the club served to communicate their desires directly to the record companies. Freeman explained, “No one had reissued any old Carter Family, so we began writing all of these record companies. Finally, RCA put out one, and I reckon it sold real good, because they put out more, and then Columbia did the same, and then Decca put out two or three.”

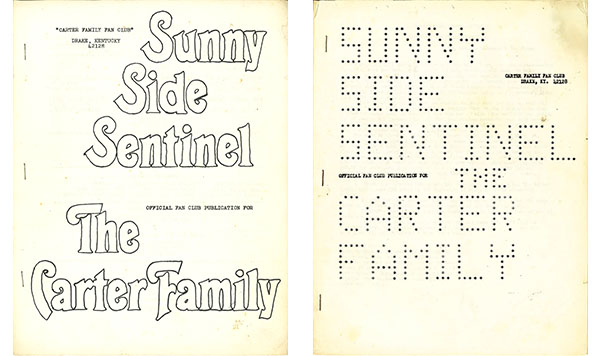

The Fan Club also kept up a long-running mimeographed fanzine called the Sunny Side Sentinel, where, for a membership fee of $2, fans and collectors could trade stories about live performances by the Carters or related artists, news bits about album releases, homemade discographies of personal record collections for sharing or for auctioning by mail, and music reviews and photos of the Carters. Interest in the club and its publication waned in the mid-1980s, after many members of the Carter Family had passed away. Although Freeman has now parted ways with most of his country 78s, he continues to ensure that the music is still accessible to his patrons and neighbors in one format or another.

Courtesy of Freeman Kitchens

Courtesy of Freeman Kitchens

All these moving parts—the shop, Freeman’s role as community postmaster, and his stewardship of the Fan Club—enabled Freeman to cultivate an international network of record collectors, music fans, and the musicians themselves and thereby document the rise of popular country music, just as it moved from rural to urban. When the Carter Family Fan Club was getting started, no one cared too much about music associated with poor, rural Southerners. Record companies and magazines saw dollar signs elsewhere, and there were no social histories of these musical forms being written by scholars yet. (I later heard from Freeman’s niece Betty that William Faulkner had written to Freeman a handful of times asking what he knew about the origins of a certain obscure folk tune. Freeman vaguely remembered the exchange, and when I asked if he had those Faulkner letters somewhere, he said, “Oh, I don’t know. I must’ve given them to someone.” He was more interested in telling me about the time Bill Monroe’s backing musicians visited the shop.) Freeman’s enthusiasm for this music and its community continues to be seen in the winding paper trail of the fanzine, which eventually servedas an important primary source to researchers, leading to sizable collections of the Sentinel in several respected university repositories as well as the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress.

But Freeman Kitchens remained humble in his task. He never saw himself as a de facto documentarian of an emerging musical culture. Freeman was not simply accruing rarities for himself; he was building a complete collection of Carter recordings so that he could make a tape of his favorite tunes to share with other country music fans down Plano Road or out in Los Angeles. “Value” is relative here, and my notions of how a music collector does his collecting have been challenged. Freeman never journeyed the back roads in search of a record. The music came to his doorstep, either by word of mouth, by post, or by providence.

One wall inside Drake Vintage Music and Curios. Photograph by Jennifer Joy Jameson

One wall inside Drake Vintage Music and Curios. Photograph by Jennifer Joy Jameson

Over the last four years, I’ve spent many Saturday afternoons hanging around Freeman’s shop, perching myself in the chair next to the register, or the stool next to the record player. These are the best spots to watch Freeman’s interactions with local people and, on a rare occasion, out-of-towners coming to the store as an act of country music pilgrimage. A visit to the store is a way to conjure bits and pieces of a murky musical past, and see its stamp on the present. But it was not just the history that kept me coming back. I’ve become a devoted fan of Mr. Kitchens himself, who signed his newsletters with this note:

In closing, let me say that I am glad, and feel that it is a great honor to be president of The Carter Family Fan Club, for to me there is no greater artists anywhere than The Carters, and I hope all of those concerned with their fan club will help me make it a great success. LET ME HEAR FROM ALL OF YOU.

YOURS FOR THE CARTERS,

Freeman Kitchens

Freeman Kitchens in his shop. Photograph by Jennifer Joy Jameson

Freeman Kitchens in his shop. Photograph by Jennifer Joy Jameson