The Bestoink Dooley Fan Club

By Will Stephenson

The American tradition of the late-night TV horror host is said to begin in the mid-1950s, with the debut of the undead and wildly popular Los Angeles personality Vampira. The name speaks for itself: As played by the Finnish-American actress Maila Nurmi, Vampira was pale and sensual, her lair outfitted with human skulls and dry-ice. She was a tour guide to Hollywood’s phantom subsurface, introducing her viewers to all manner of horror films classic and obscure. Before long, every city in America had one like her, usually with a name like Morgus the Magnificent, Count Gore De Vol, or Ghoulardi, each of them attuned to their own region’s specific rhythms and worst fears. At their best, they were like translators, necessary extensions of the movies themselves.

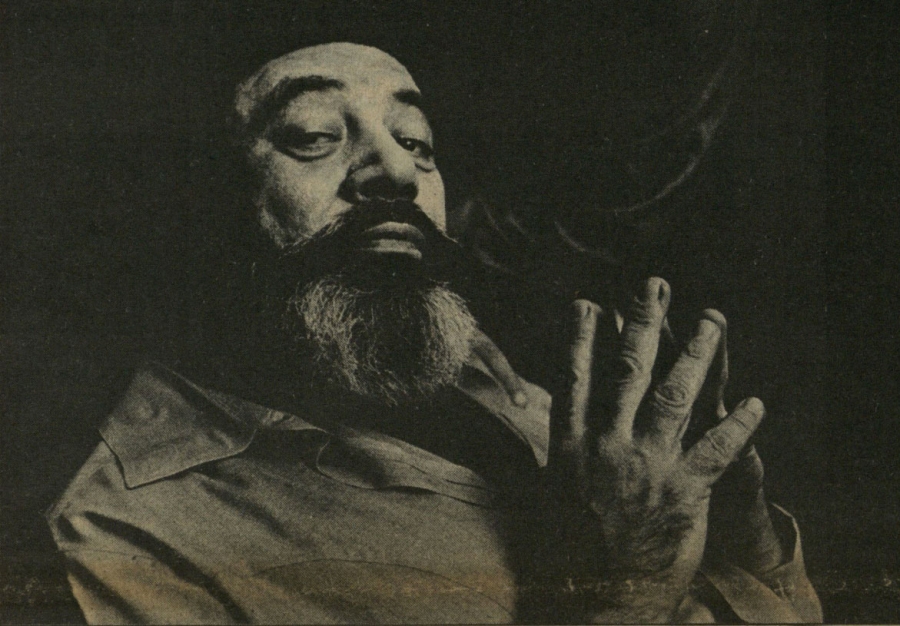

One of the most distinctive of this first wave belonged to Atlanta. He was called Bestoink Dooley and was almost single-handedly responsible for acquainting a certain generation of Southerners with the big-screen horror canon in the 1960s. An invention of local actor George Ellis, Dooley wore something like a magician’s uniform, complete with a bowler hat and a flower on his lapel. Big Movie Shocker aired Friday nights at eleven-thirty on WAGA-TV Channel 5; Dooley showed The Mummy and Cat People and The Wolf Man and The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. “Some people say he’s the ugliest, most sinister-looking man in Atlanta,” reported the Atlanta Constitution in 1963. Dooley was the face of Georgia’s nightmares.

Ellis himself didn’t see it that way. “I don’t try to scare people out of their wits,” he told the paper. “I’m more like a slobby comic in a horror situation.” Unlike many of his counterparts in other cities, Bestoink Dooley was neither demonic nor especially villainous. His approach was more experimental than that, eschewing graveyard kitsch for spontaneity and warped humor. You can get a sense of it from tributes online: the time he spent the bulk of an episode hiding in a cardboard box; the time he broadcast from the rafters of the studio, refusing to come down; the time he dropped the horror format altogether and screened Black Orpheus instead. He became a phenomenon—buttons were issued for the “Bestoink Dooley Fan Club”—and began appearing out in the city, hosting standing-room-only screenings of Journey to the Center of the Earth and absurdist poetry readings.

At the height of his TV infamy, Ellis started making films of his own. I first came across his name on the back of a VHS copy of a 1965 movie called The Legend of Blood Mountain, which I bought at a flea market outside of Athens, Georgia, several years ago. To watch it is to pass through a membrane into what the scholar Jeffrey Sconce has called “paracinema”—the lo-fi, incidentally avant-garde universe of B-movies, propaganda, and pornography. Movies that either fail to meet the standards of classical editing and coherence, or which gloriously never bother to attempt them. Shot in Stone Mountain on a budget of $50,000, Blood Mountain starred Ellis in his Bestoink Dooley guise, here reimagined as an aspiring Atlanta journalist. When he learns that “according to reports, the mountain is bleeding again,” he begs his editor for the story and ventures out to investigate the odd geological event, which he suspects (correctly) might be related to the mythical Blood Mountain monster.

The film’s carelessness has an unsettling, almost psychedelic quality, a strange alchemy by which cost-cutting production values and regional authenticity are filtered through a poor VHS transfer to make for something trancelike. It’s either the worst film ever made in Atlanta or the very best—a lost masterpiece of the Deep South drive-in circuit. As the horror filmmaker Herschell Gordon Lewis once said of his own work, “It’s no good, but it’s the first of its kind, therefore it deserves recognition.”

Ellis got recognition. A 1967 New York Times article on the rise of low-budget Southern film production cites The Legend of Blood Mountain as a crucial pioneer of the form, for better or worse. “As far as anyone can tell there have been no panic waves rolling through Hollywood, or even toward it, but a handful of people in the South with a few dollars and a penchant for gambling are quietly trying to take a piece of the action for themselves,” the article says. “Whether this represents cultural advancement for the South is debatable.”

The author of the article was the great Atlanta journalist and Hank Williams biographer Paul Hemphill. He must have been at least somewhat sympathetic to Ellis’s efforts, because he followed up by spending a few days in Clayton, Georgia, on the set of one of the actor’s next projects, a backwoods moonshine saga called There’s a Still on the Hill. Hemphill found the crew running low on funds and essentially teaching themselves how to make a movie as they went, shooting in local grocery stores and staying up late arguing in motel rooms clouded with cigar smoke. Ellis seemed content, even defiant, about what Hemphill termed his “hillbilly productions.” “It’ll get better for me,” he told the writer. “I could go to Hollywood right now and do bit parts, I think, but I’ve got no desire to the leave the South. This is better than a screen test and a job in a hamburger joint.”

True to his word, Ellis dedicated the rest of his film career to the type of work that would later be described as “hixploitation”—that specific strain of grindhouse cinema that observed Southern habits through a grotesque, funhouse mirror. Films, in his case, with titles like The Gold Guitar, Swamp Country, and Honey Britches (later re-cut and re-released as Demented Death Farm Massacre). Viewed charitably, the genre was an attempt to seize the means of production, to allow Southerners to tell their own stories on film, rather than accept the ones Hollywood was telling on their behalf—and Ellis was on the front lines of the movement. His highest profile role came in 1975, as the power-hungry Jake Rainey in Moonrunners, a bootlegger epic narrated by Waylon Jennings. What should have been his triumph, though, was undercut in the aftermath of its release. A few years later, the director, Gy Waldron, adapted the film for television with much greater success, in the process renaming it The Dukes of Hazzard. The Jake Rainey character was recast, and renamed Boss Hogg. It would be the closest George Ellis ever came to immortality.

Ellis was an unlikely delivery system for “hillbilly productions” of any sort. He was raised in Newport News, Virginia, by parents who had immigrated from war-torn Syria and Lebanon. His father was the proprietor of a fruit stand, who tried to immerse his children in the culture he’d left behind (they ate kibbeh on Boy Scout camping trips, to the bewilderment of the other kids).

After a stint living at home and working as an apprentice draftsman at a shipyard, Ellis had moved to Richmond, where he’d married a woman named Gwen and had a son, Michael. The family relocated to Atlanta in the early 1950s; Ellis had been hired to design the window displays at a local department store, Davison’s, and to sing with the Atlanta Opera Company. Not long after they arrived, he and his wife began to establish themselves in the local theater community. But the relationship was strained, and by the end of the decade, the couple had divorced. Gwen soon left the country for the Philippines, taking their son with her. Around this time, Bestoink Dooley was born.

As he was getting into movie-making, Ellis also opened a theater, the 96-seat Festival Cinema on Spring Street. One of the paradoxes of Ellis’s career, in hindsight, is that alongside his run of cheap exploitation films, he maintained a parallel career as Atlanta’s first great arthouse film exhibitor. It adds a layer of complexity to his work, to know that his own taste was impeccable—he understood the full range of cinematic possibilities and would have seen exactly where his films fit into that spectrum. Around the time Demented Death Farm Massacre was hitting theaters, Ellis was introducing Atlanta to the French New Wave and the New German Cinema, hosting retrospectives of Chaplin and Bergman. “George is the father of the art film in Atlanta,” the theater entrepreneur Glenn Sirkis said in the 1980s. “George is the one who groomed the audience for all of us.”

Perversely, Ellis designed the Festival Cinema to be the kind of place where his own work would never be shown. Atlanta magazine described it as a venue where “patrons would often come as much as 30 minutes before the show started to sit in the plush lobby in white sculptured chairs and leaf through copies of Sight and Sound or talk in muted voices and sip the complimentary Viennese coffee.” The Atlanta moviegoer, Ellis told the magazine proudly, had come of age. But as Atlanta’s downtown became increasingly deserted in the late sixties—an effect of new interstate construction and the city’s violent attempts at urban renewal—so did Ellis’s lobby. Within a few years, the Festival was $40,000 in debt. As a measure of last resort, Ellis switched to showing only X-rated films, and profits soared. “In two years of showing trash I was able to make up for the money I’d lost showing art films,” he said later.

His career as a porn mogul ended when Ellis was arrested one night on obscenity charges, escorted from the projection booth and removed from the premises in handcuffs. He was forced to close the Festival, though he couldn’t be kept down for long. Emboldened by the city’s emerging counterculture, he revived the arthouse dream and, in the 1970s, opened the Film Forum at Ansley Mall, followed by the Film Forum on Peachtree and, later, the Bijou Cinema. You can trace the roots of Atlanta’s film culture through these theaters.

A brutal irony: If Ellis’s own films weren’t considered good enough to find a wider audience, the films he screened at his theaters were considered too good to do the same. One afternoon in 1974, the new ownership of the Film Forum appeared in the lobby and told George and Michael (who had returned to America and was working as his father’s projectionist) that they were relieved of their duties. The front office had decided the place could be more lucrative under different management. (They were probably right: “I’m not motivated monetarily,” Ellis once told the Constitution. “It’s to the point of being a fault.”) But Ellis had become one of the most beloved figures in Atlanta, and the city wouldn’t stand by and see him locked out of his own theater. The underground paper of record in those years, the Great Speckled Bird, ran an urgent cover story in protest—SHUTOUT AT THE FILM FORUM—and led a boycott that continued until the owners agreed George would be reinstated. “One man is primarily responsible for the introduction and dedicated perpetration of serious film in Atlanta,” another newspaper announced after the debacle. “He is George Ellis, who with his son Michael, has probably done more to raise the culture quotient of this city than any other person.” Ellis’s own films weren’t mentioned in the coverage.

By 1980, Ellis had resigned himself to obscurity. It had become clear to him that his filmmaking career was over, and his theaters, despite the local reverence, had continued to barely break even. Former employees recall a print of The Legend of Blood Mountain gathering dust in the corner of the projection booth. It was never screened—Ellis was apparently ashamed of the film—but it was always there, as though one day he might change his mind. After he sold the Bijou, he told the Constitution it was “kind of a shock to be 63 and suddenly not working.” He was proud of his place in the city’s cultural ecosystem, but he acknowledged struggle. “We’ve never had or made much money,” he went on, adding, “I don’t want to sound like a loser. I’m a survivor. Everything will be all right.”

One night in 1983, Ellis was found dead (probably a heart attack) in a motel room in Midtown, where he’d been living alone. For the last year of his life, he’d been dreaming of his final movie theater, the one that would succeed where the others had failed. He called it the Masterpiece. He’d been renovating a site on Euclid Avenue in Little Five Points, but the building hadn’t yet been completed. At a memorial in his honor, his business partner announced that the theater would be finished and renamed the Ellis. “The name Ellis conveys a lot more warmth and emotion in Atlanta than the name Orson Welles,” he said without hyperbole. (The Ellis Cinema survived for about four years; today, the building houses the Variety Playhouse, one of the city’s best-known music venues.)

Ellis’s memorial was attended by a diverse cross-section of the city. The arts critic Eleanor Ringel wrote a dispatch which noted, among others, “a quiet knot of Indians who’d gotten to know George over the years because he showed Indian-language films for them.” The playwright Jim Peck gave the eulogy, which he began with a nod to Ellis’s ethnicity (something never otherwise acknowledged in print). Peck reminded the crowd that Ellis had always insisted “that he was nothing more and certainly nothing less than a Lebanese shopkeeper.” Ringel herself put it more dramatically. “George let there be light in Atlanta,” she wrote.

“Outskirts of the Southern Canon” is a part of our weekly story series, The By and By.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.