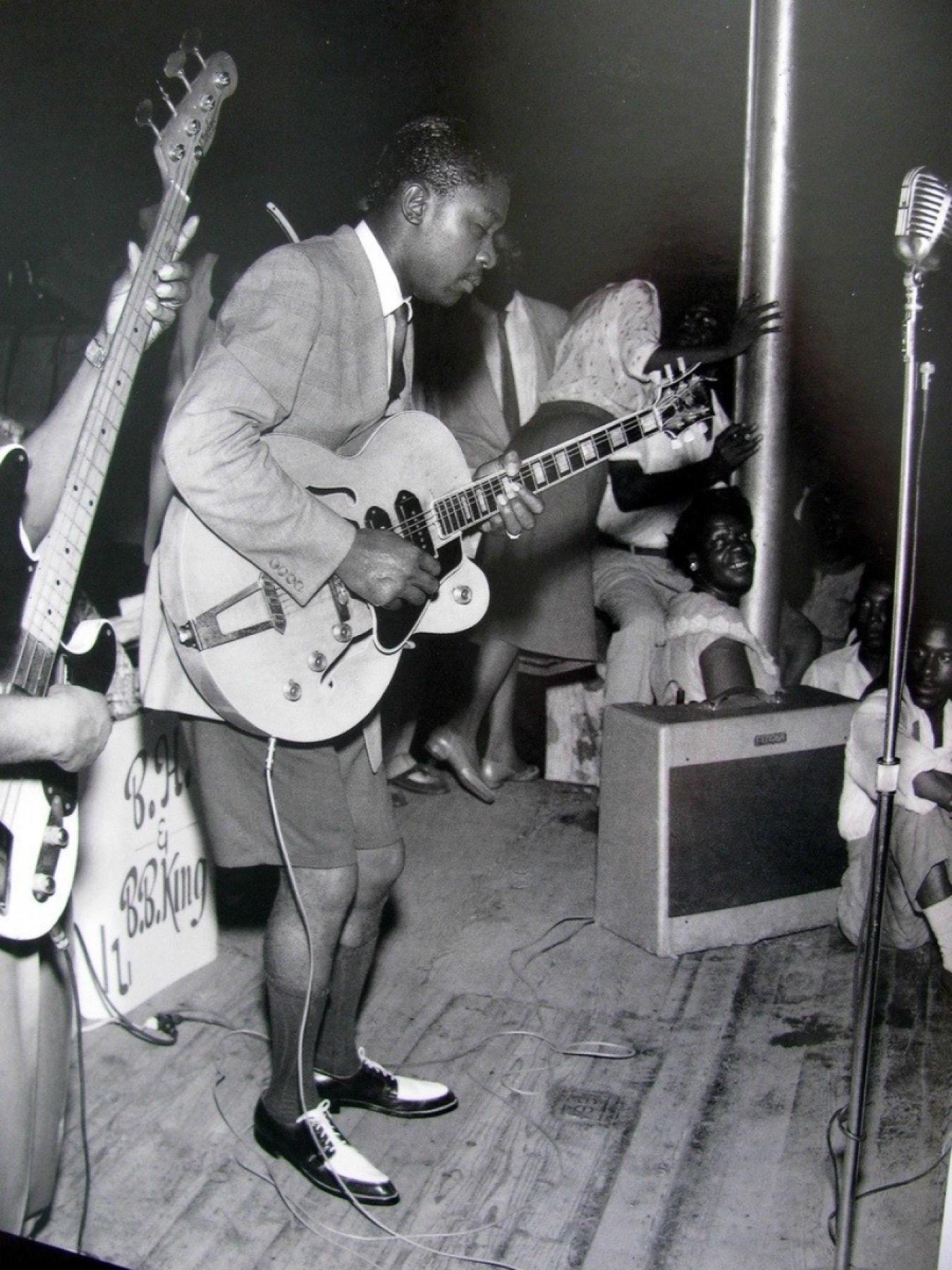

A young B.B. King in shorts, photographed by Ernest C. Withers

The Happiness Blues

A surfeit of joy in B.B. King’s early singles

By Ted Scheinman

B.B. King had near-limitless patience—a magnanimity toward his fans and a generosity that compelled him to nurture younger talents. This patience did not extend to white listeners who misconstrued the blues as a posture of grief, a ritualized performance of suffering. “Scholars love to praise the ‘pure’ blues artists or the ones, like Robert Johnson, who died young and represent tragedy,” King writes in his autobiography. “It angers me how scholars associate the blues strictly with tragedy.”

King articulated this sentiment in 1996, but he’d been playing it his whole career. Since his first recordings in the 1940s, B.B. King exuded a sunny elegance very much at odds with the tragedians of the early blues. You could see it in his raconteur’s stage-banter and that perennially cheerful visage, but mainly you can hear it in the playful yelp of his guitar, Lucille. Indeed, King’s breakout recordings challenge every facile notion of doomstruck minstrelsy that the Woodstock generation would come to associate with the blues. The popular blues myth, as Amanda Petrusich wrote in this magazine, “lionizes and martyrs the outlier, and incentivizes anguish” to a fault.

To understand the happy bluesman in his early exuberance, look to the run of hit singles in the 1950s: “Three O’Clock Blues” through “Rock Me Baby.” Here we find King taking the blues stomp of Sonny Boy Williamson, merging it with the just-short-of-jazz urbanity that King so admired in T-Bone Walker, and allowing the horns just enough glitz to make the whole rig swing. He transposed piano riffs onto the guitar, played solos that expanded the blues palette far beyond the sacrosanct pentametric scale, and redefined his instrument without ever really learning how to play chords. As a guitarist, I still haven’t forgiven him this last point: the same syncopation, the same idiosyncratic and startling phrases that mark his solos would have made King one of the most interesting rhythm-men in our planet’s history, if only he had deigned to play a few chords here and there.

Most of all, King found a wide audience with remarkable alacrity, especially for a bluesman without a myth at his back or a hellhound on his trail. In 1951, he was averaging a few dozen bucks a week, rarely breaking $100. Within three years, having formed the B.B. King Review, he was pulling between $2000 and $3000 a week for sold-out live shows across the continent, as he toured behind those high-charting singles: “Woke Up This Morning (My Baby’s Gone),” with its sly shifts between shuffle and swing; “Ten Long Years,” with those exquisite moments of falsetto; “Sweet Little Angel” and “Rock Me Baby,” both stylish gestures in the direction of Chicago. King’s voice on these breakthrough records is clean, almost too clean. Far removed from the throatier, more overtly “soulful” approach on his most famous recording, “The Thrill Is Gone” (1969). That clean period could well be called a concession to white audiences; more important, King’s voice on these early singles, before he became a spokesman for the blues, captures the unmuddied joy of a man concerned with creating a fundamentally celebratory art, separating himself at once from the hoodoo baggage that attended Robert Johnson and the more contemporary gruffness of Muddy Waters.

Throughout the ’50s, even as he sang of lovesick insomnia and “Troubles, Troubles, Troubles,” King was really just hosting a party. Two decades later, in 1978, Pete Townshend would describe rock & roll as therapy, a joyous release: “Rock music is important to people because in this crazy world it allows you not to run away from the problems . . . to face up to them, but at the same time to sort of dance all over them. That’s what rock & roll’s about.” B.B. King, who pushed popular music toward rock as much as any blues guitarist this side of Buddy Guy, might well agree—though for King, as for Guy, the music was always much more important than the problems.

B.B. King was most exciting when he created music out of his own deepest contradictions. He made the blues a vehicle for joy and ushered the idiom into its most sophisticated and most popular manifestations. To a certain kind of observer, King’s philosophy of music was also his mode of living. He gave self-pity no quarter and knew that to keep moving was to keep living—hence the 300 plus shows he played across the globe each year, and his refusal to succumb to diabetes. King’s smiling defiance of the blues is what made him its most compelling and long-lived ambassador, a role now entrusted to the worthy figure of Buddy Guy.

The King is dead; long live the thrill.