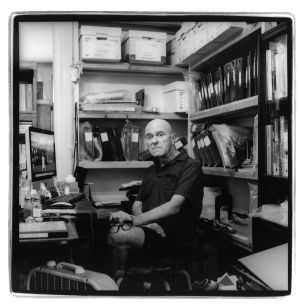

LZBII at desk, moving. All images © Guy Mendes

I WAS A WITNESS

By Laura Relyea and Guy Mendes

The Archive of Louis Zoeller Bickett II

It’s a brisk February afternoon in Lexington, Kentucky, and Louis Zoeller Bickett II and I are sitting in his office, which is lined with five hundred binders. A few shelves of author-signed books, all of them tagged and indexed, stand in the room behind me. Our coffee mugs are not tagged, but the small Windsor chair I’m sitting in is. The front room, by the doorway, is packed floor-to-ceiling with five hundred and seventy-seven boxes, individual works, paintings, and found objects. In the binders that line the office are bills, receipts, letters, postcards, notes, gallery cards, portraits of Queen Elizabeth II, comic strips from the Lexington Herald-Leader, obituaries, plane tickets, and take-out menus—the detritus of a life, every scrap of it described, tagged, and cataloged in a six-hundred-fifty-page master index. For over three decades, Bickett has lived, not around, but within the accumulation of these works, what he calls THE ARCHIVE.

“If you save a matchbook, it might prove that you were at this restaurant in this certain period in your life. It says something about you and it says something about society,” Bickett says. I look around the room and think of all the papers crumpled in my drawers, purses, and back pockets, the matchbooks sitting by the candles on my mantel in Atlanta. I’d made the four-hundred-mile drive from Georgia because a friend had been telling me stories about Bickett, about what was here. And now, sitting across from him, in a house filled with stuff, I found myself mesmerized. Bickett’s curatorial hand transformed what would be menial objects into artifacts: dirt from Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s graves, a wax-sealed jar of murky water from the Mississippi, a crowd of bleached animal skulls that frame his front porch.

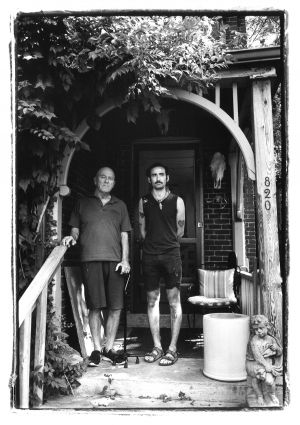

For the last five years, Bickett and his partner, Aaron Skolnick, have lived in one of the large antebellum Victorians that mark downtown Lexington, a town better known for its college basketball and horse racing industry than its contemporary art. Now, the couple is searching for a single-story home because sixty-six-year-old Bickett has increasing difficulty climbing the winding stairway. In preparation, they are, today, moving a portion of THE ARCHIVE into one of Bickett’s two 10' x 20' storage units. One of the young men moving Bickett’s belongings yells over from the front room, “Good Lord, Louis, what is in the boxes with the green labels? This is heavier than sin.” Bickett takes a moment to think: “Green labels? That’s three hundred sixty-five liquor bottles of piss. Be careful with those.” Bickett then tells me about a friend who had broken one of the bottles that Bickett gifted him: “He thought he’d have to move. He couldn’t get rid of the odor.” Bickett’s laugh trumpets through the house. Portions of THE ARCHIVE have been shown in Kyoto, Kiev, Manhattan, Moscow, and, well, Kentucky. But I couldn’t figure out what this man was—compulsive hoarder? curatorial genius? amateur historian?—or how such a man begins such a project, now more than thirty-five years in the making.

A self-taught conceptual artist, Bickett was born to a prominent, long-established Clark County family in 1950. He was raised in the county seat, Winchester, an old tobacco town with less than ten thousand people; in his early thirties he moved to Lexington, where he began to collect and catalogue. Bickett lived for two decades on the same street where he waited tables, in a second-floor walk-up, seven-hundred-square-foot apartment that was at once his home, studio, and archive. Five years ago, Bickett and Skolnick moved in together into the Victorian, THE ARCHIVE in tow. Now they are moving again. I am here as awkward inquisitor, untagged. Next to my chair stands a five-gallon Home Depot bucket, filled to its brim with golf balls. Its tag reads:

THE ARCHIVE OF LOUIS ZOELLAR BICKETT II: 282 Golf Balls Retrieved by G.M. Stewart from the Bloody Point Golf Club, Daufuskie Island, South Carolina.

Also stamped on the tag: the date, a square red cross, and the phrase “Memento Mori,” alongside Bickett’s signature in ink. (Stewart was an ex of Bickett’s, he said; these balls were a gift from Stewart’s job at the country club.)

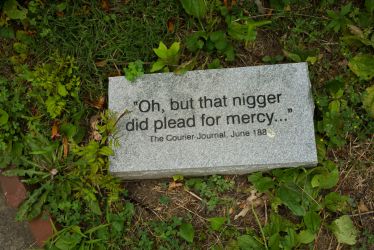

These tags are on just about everything I see in the house; the date, a stamped red cross, Memento Mori, Bickett’s hand. All items in THE ARCHIVE are tagged this way before being organized and recorded in the master index. Dog collars, crutches, Bickett’s father’s cane collection, coats, dolls. Some items are isolated iterations and others take part in discrete conceptual series. One such series is the fifteen black-face lawn jockeys—the short, cartoonish kind; racist hitching posts—each holding a sign made by Bickett that marks a hate crime that occurred in Kentucky. Another: twenty-five volumes of obituaries, many of which accumulate record of the gay men who passed away from AIDS in the eighties and nineties.

THE ARCHIVE also includes digital works, which are housed in the desktop computer (tagged) and external backup drives (tagged) that sit on the simple wooden table (tagged) that Bickett uses as a desk. More than seventy percent of the collection is scanned and digitized, and some items exist only online, including ten thousand selfies. Like the tangible collections, some of the digital files are in series, like the work Will Pray For Tickets, a reference to the regular sight of University of Kentucky basketball ticket scalpers. In these photographs, Bickett wears a full hijab, holding objects ranging from the Bible to a tank of gasoline.

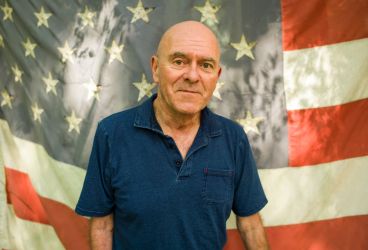

The individual contents of THE ARCHIVE are easier to describe than the project itself, which Bickett says includes his office and, one day, himself. “[THE ARCHIVE] is just saying, like at Thermopylae, ‘I am here,’” he told me. “You know? I was here. I was a witness.”

A year before I met Bickett, he was cycling one hundred miles a week and waiting tables at Á La Lucy’s, a white tablecloth restaurant where he’d worked for thirty years. Then, in May 2015, his life changed. “I had this feeling, when I went to walk,” Bickett said. “It was almost a disembodied feeling. When I went to put my foot down, I would think that it was on the floor, but it was really still about two inches above it.” By November, that incorporeal feeling was diagnosed as Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (or ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease). A month later, Á La Lucy’s closed its doors and Bickett found himself faced with the challenge of supporting himself through his final and now handicapped years, while also hatching a plan for THE ARCHIVE’s survival. By the time I met him, Bickett was having difficulty moving around; his walker (tagged) went with him everywhere.

There is no known cure or treatment for ALS; Bickett’s nervous system will continue to degenerate. Eventually he will be fully cognizant of his surroundings, but incapable of moving, talking, or breathing on his own. Nevertheless, he has been motivated by his prognosis—setting to work organizing THE ARCHIVE, as well as incorporating new items. To the six-hundred-and-fifty-page index Bickett has lately added two binders of catalogued health reports and doctor’s notes. “In my family, people live to be pretty old,” he said. “I guess that I just assumed I would too.”

From a distance, it’s easy to dismiss Bickett as a highly organized hoarder; an artist who’s Obsessive Compulsive Disorder has become its own installation piece. But after nearly ten hours of interviews, seventy-five emails, and countless phone conversations with Bickett, I realize that those assumptions couldn’t feel farther from the truth. It strikes me now how many different ways Bickett described his project to me: as an archive, a diary, a historical narrative, a memory; it’s about death, life, sex. THE ARCHIVE is, in a basic sense, human—about you and me, as much as it is about him. I see an image of Bickett holding up a Holy Bible in a Hijab and am face-to-face with my own misgivings with religious practice. I see a bucket of golf balls and feel nostalgic for an ex of my own who once transcribed, by hand, seven songs for me to learn to play on piano. His dirt samples gathered from each of Kentucky’s one hundred and twenty counties strike in me a longing for a part of the country I’m growing to love more and more. Binders. Twenty-five binders, of obituaries. I look at them before I leave the Victorian that cloudless Lexington night. I decide: I want to collect Bickett’s when he’s gone.

https://main.oxfordamerican.org/item/943-i-was-a-witness#sigProId9b73be9e8e

Enjoy this story? Sign up for our newsletter.