Food Is Us

Dedicated to Julia Reed, Randall Kenan, and Marie Dutton Brown

By Alice Randall

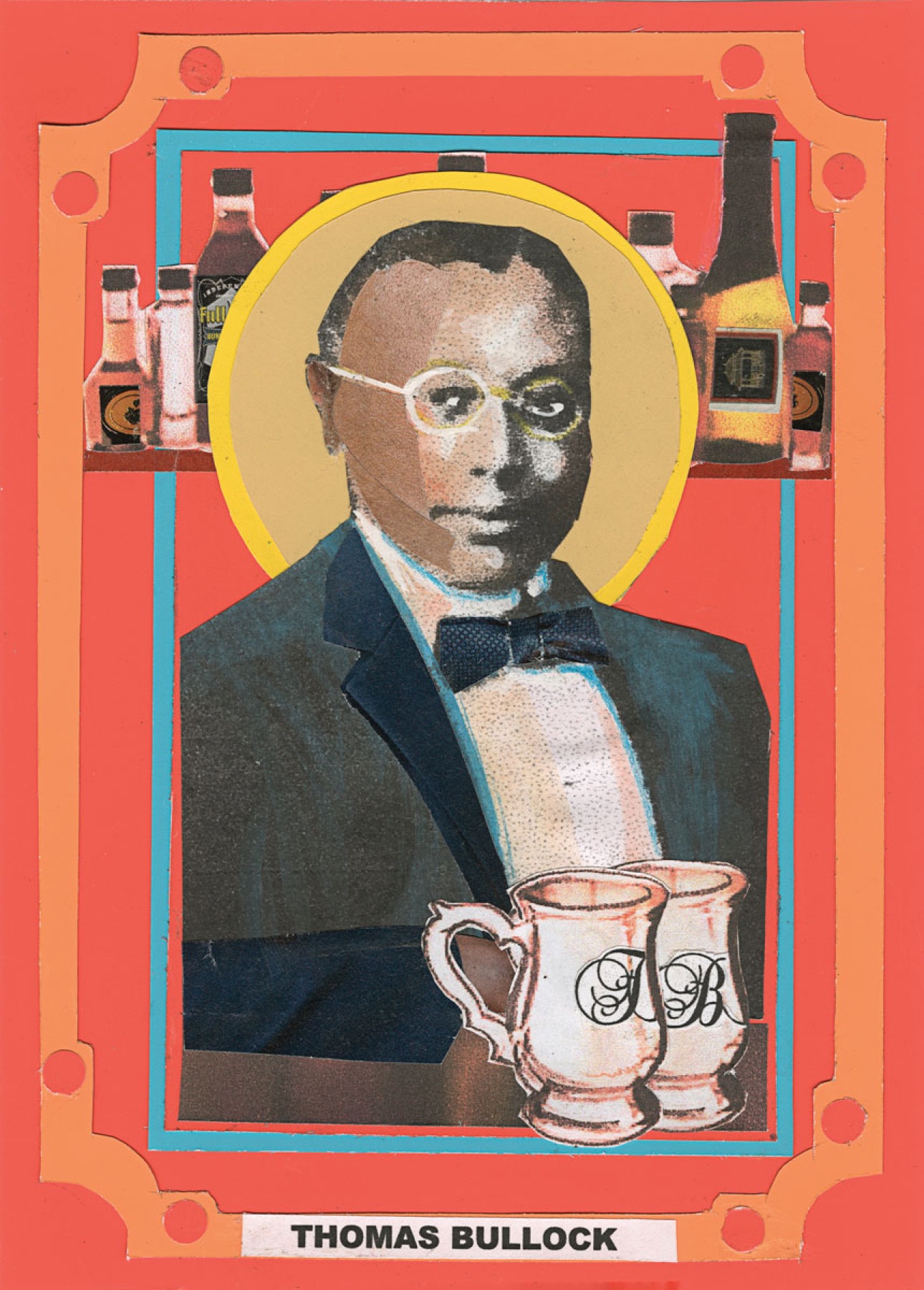

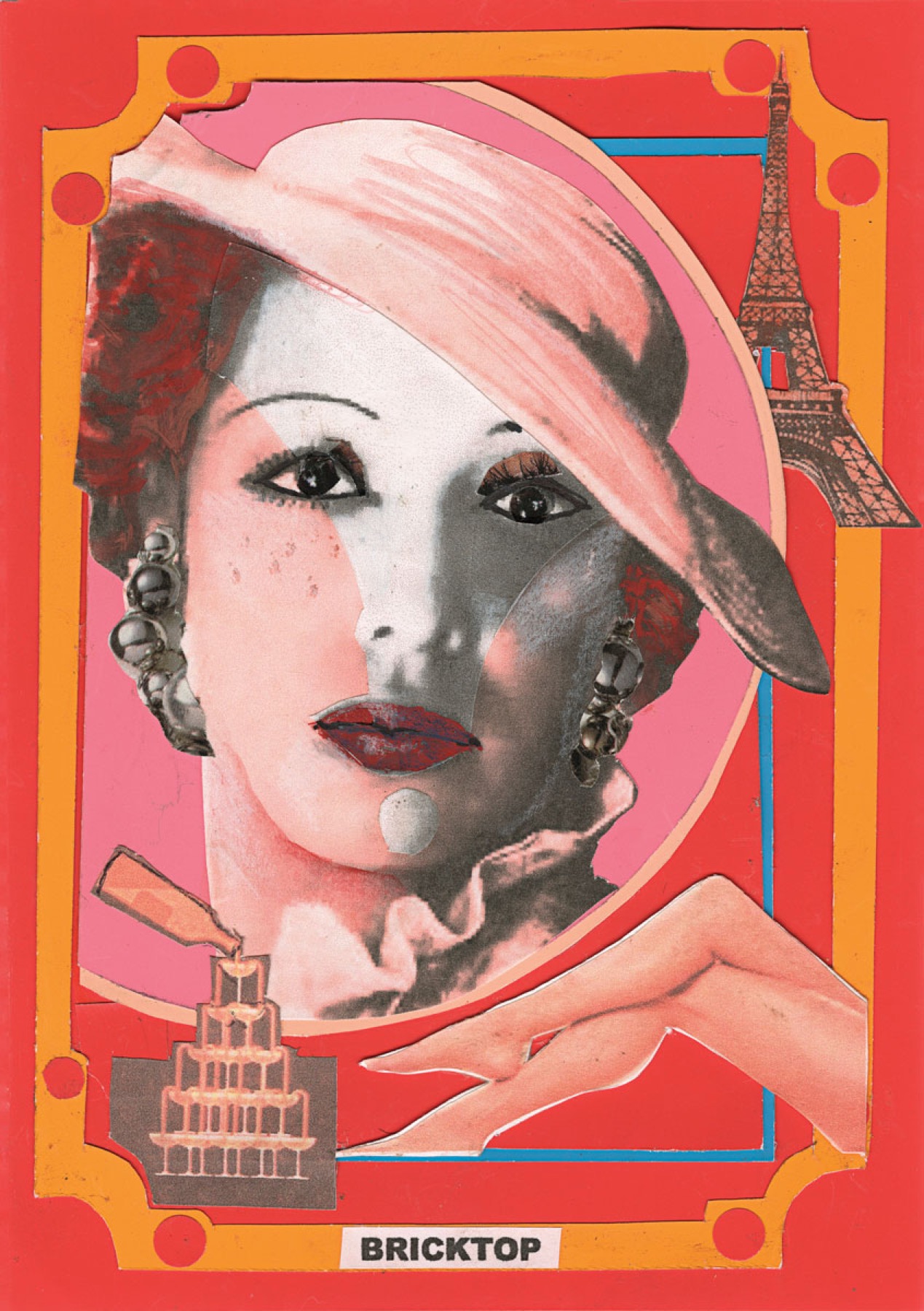

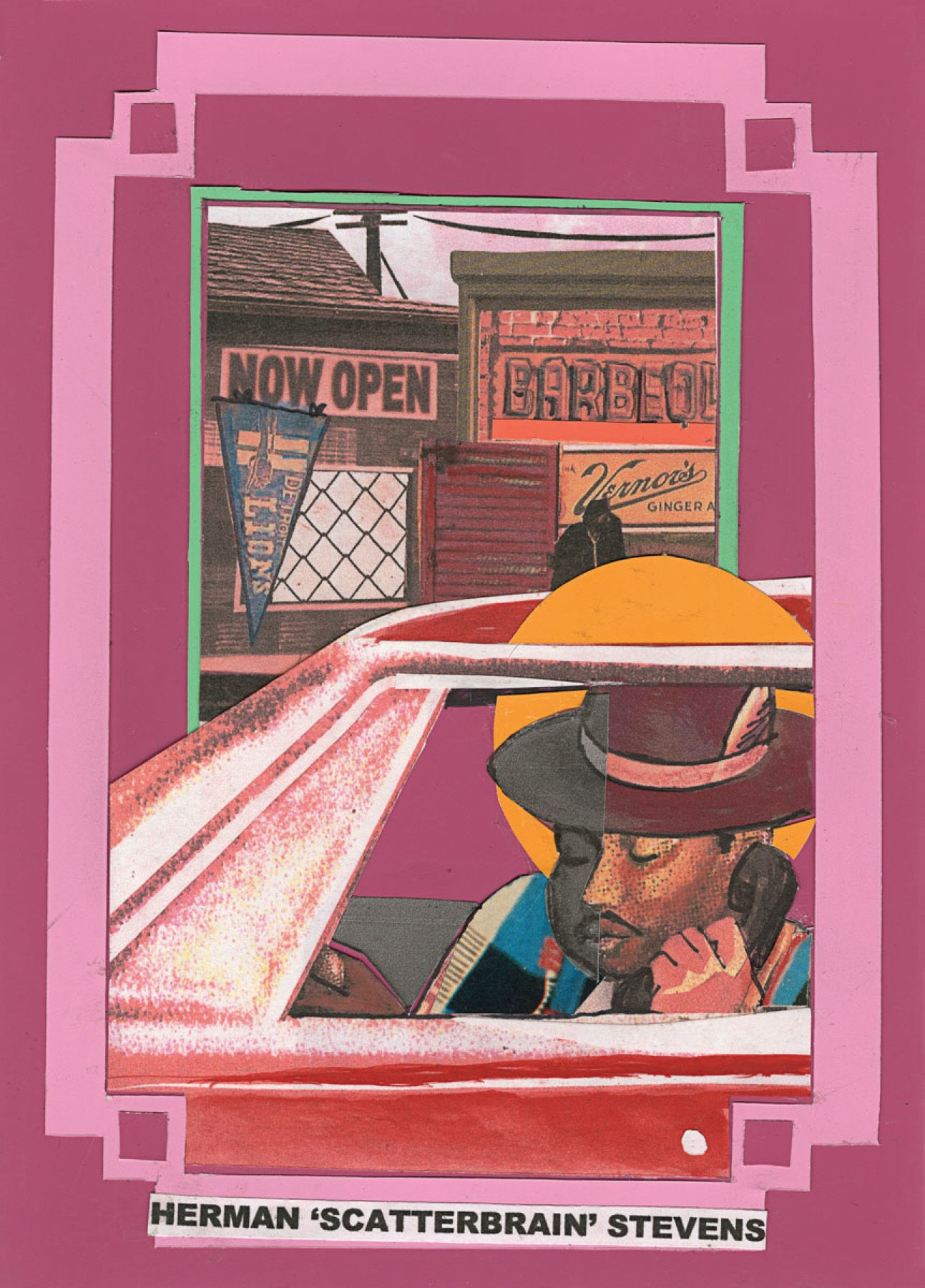

Alice Randall commissioned portraits by artist Jimmy James Greene to commemorate the “saints” featured in her novel Black Bottom Saints (2020)—including an extraordinary bartender, barkeep, and barbecue man.

Southern food truth: We eat the best meals with family and friends. And cook the best meals for family and friends.

Fortunate are we who with family and friends cook, serve, eat, then clean.

Quiet as it is kept, and widely as it has become forgotten, those who do the cooking and the farming know that those who only eat what is cooked for them and served to them never eat as well, measured by flavor on the tongue or justice in the world, as those who sample straight from the pot with a clean tasting spoon.

On August 28, 2020, the world of letters and the world of food—the world of truth-telling about the South—lost the two people who knew this best: Randall Kenan and Julia Reed. And I lost two friends.

Julia was born in Greenville, Mississippi, on September 11, 1960. Randall was born in Brooklyn, New York, on March 12, 1963. There were barely a couple of years between them. Neither lived to see their sixtieth birthday. They died on the very same day, each of them leaving behind a legacy of extraordinary food writing.

Julia wrote with swagger and verve about what I call the “pool and patio South”—the white South of country club dinners and garden parties, yes, but also raucous throw-downs studded with wit, wild women, old whiskey, and remorse. I well remember how in November of 2010, she took me for a classic eat-well-drink-much-talk-loud dinner at Doe’s Eat Place in Greenville, which she first visited in utero.

In Randall’s South, families fished together to fill the freezer with good things to eat. Writing about visits to Topsail Beach in North Carolina, Randall wrote for Garden & Gun: “Croakers, mackerel, pompano—our freezers would be stuffed for the year. Catch and release was never a thing for my family.” He also described how the “black folk were confined to two piers.” About this de facto Jim Crow, he commented, “Though the bathroom and shower facilities were subpar, I warrant the fried shrimp, fried flounder and mullet, coleslaw, hush puppies, and hot dogs were just as good, if not better.”

The very first time I dined with Randall Kenan it was in my family home in Nashville, a house that has entertained John Egerton and which shelters chairs that have held Malcolm X and Adam Clayton Powell, a four-square that is home to six thousand cookbooks, including one my daughter and I wrote together, Soul Food Love. Our cookbook includes a recipe for sweet potato broth that is presented as a tribute to Randall Kenan and his first novel, A Visitation of Spirits, which is set in rural North Carolina and studded with food memories. That first dinner, I fed him pepper jelly coins, cornbread madeleines, and a stew of black-eyed peas, kale, and sweet potato.

Randall Kenan loved sweet potatoes. He loved to eat them, talk about them, and read them. He was proud of the fact that fifty percent of the nation’s sweet potatoes came from the place he called home, North Carolina. One year at an event for his beloved Southern Foodways Alliance, he proclaimed that Invisible Man was arguably the great American novel and that the “meat” of the story was an “edible root”—the sweet potato, called in Ellison’s text a yam. He drew a parallel between Ellison’s line, “I yam what I am,” and God’s response to Moses in Exodus Chapter 3, the chapter that talks of delivery from a place of slavery into a land of milk and honey, with these words in the King James version: “I am that I am.”

He ended his talk with a clarion call that serves as a fine epigraph for this issue of the Oxford American, an issue devoted to exploring intersections between food and art and identity:

For me, the hallmark of food in literature, raised to the level of art, is food interacting with character. Food as character. Food doing stuff. Food being stuff. Just as it happens with our flesh and blood, our mouths and our bellies and our memories. The best writers, the better writers, know that food is identity. Food is alive. Food is us.

Randall was such a fine writer. In his final publication, If I Had Two Wings, a collection of short stories, he writes of Howard Hughes coming to North Carolina to beg a woman to cook for him as her mother had once cooked for him. She refuses. She refuses to sell her services and does not offer her recipes. “The Eternal Glory that is Ham Hocks” is a stunning work of fiction that conveys truth about what can and cannot be bought and sold in America.

When one of my very favorite artists, a young man I had loved since he was three years old, Justin Townes Earle, was found dead on August 23, 2020, the same brutal week Randall and Julia died, chef Tandy Wilson, owner of Nashville’s City House, brought food to my home. It was chicken roasted in the open wood fire, the meal Justin loved to eat at City House on a Sunday night. Chef did not charge me for the repast. In this issue, Tandy offers a beautiful meditation on giving away food, followed by a recipe from his pastry chef, Rebekah Turshen. Her Sweet Potato Chess and Meringue Jar-Lid Pies are cooked in mason jar lids, a concession to COVID that is both a triumph of culinary bricolage and a sweet kitchen mashup.

The essay and recipe round out our special section presented in tribute to sweet potato pie, which also includes Tiana Clark’s tale of two pies—the sweet potato pie that almost killed her, and the one that healed her—and Ayana Contreras’s riff on the representation of the sweet potato in pop culture. (Look for her playlist of sweet potato songs, which reminds me again that while the South’s politics and economics give us reasons for shame, the region’s music and food make us proud.) In her short story “Sweet Potato Pie,” originally published almost a half century ago, Eugenia Collier serves up classic brilliance. Her story is a sly, feminist, and feminine commentary on eating-while-Black and feeling shamed and shameless.

All of the writers in this issue help us see the unseen and hear what is unsaid. Lokelani Alabanza and Donna Battle Pierce shine a light on forgotten Black women food entrepreneurs: Alabanza brings us Nashville’s Sarah Estell, who made and sold ice cream through enslavement to the onset of the Civil War, when some were beginning to claim their freedom, and Pierce brings us Missouri’s Annie Fisher, successful purveyor of the beaten biscuit in the early twentieth century.

Kali Grosvenor and Michelle Lanier share a conversation that loops the past into the future, a conversation that is a model of what happens at a Southern welcome table, a conversation started by names that are often called and deserve to be called again, including so many names that haven’t been called often or loud enough—names that have been erased, names that have been obscured, names we commit to uncovering.

Reading their conversation, I thought of Marie Dutton Brown. As a literary agent, Marie has championed significant Black culinary voices, shepherding into print titles that include: B. Smith’s Entertaining and Cooking for Friends, Sallie Ann Robinson’s Gullah Home Cooking the Daufuskie Way, and Valinda Johnson Brown’s Succulent Tales. As one of the first Black editors in mainstream publishing, Marie edited two soul food classics that have both found their way into this issue, Vibration Cooking, by Kali’s mother, Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor, and Spoonbread and Strawberry Wine, by Carole Darden and Norma Jean Darden. Scholar Psyche Williams-Forson, author of the excellent book Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs, pays homage to the Dardens in her essay “A Weary Traveler in a Familiar Land,” which is also a soufflé of travel remembrance and reckoning noir on the Eastern Shore of Maryland.

I’ve never met the restaurateur Brad Johnson, but I’ve eaten at his restaurant Georgia in Los Angeles, and I grew up hearing wonderful stories of writers, musicians, and everyday folk eating at his father’s restaurant the Cellar, on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. As a young woman out and about in New York with the likes of Faith Ringgold, Marie Brown frequently found her way into the Cellar, and she brought Brad to my attention. I’m so glad she did. In Brad’s masterful feature essay, we get a glimpse of the ways in which the worlds of film and music swirl into the world of food, and more significantly, what is and isn’t “peasant food”—and why that matters. Echoing Donna Battle Pierce’s reflection on Annie Fisher, Brad writes of how meaningful it would have been had he learned of Black culinary trailblazers earlier in life: “With more inclusive documentation, perhaps future generations of aspiring entrepreneurs will be inspired by their stories.”

This photograph was taken on January 20, 2021—Inauguration Day—by Caroline Randall Williams, whose poem appears in this issue. Alice Randall, visiting her daughter’s home, is standing atop a raft assembled by the artist Herb Williams from cookbooks gifted by Mimi Oka (of Orphic Fodder). Randall is wearing pearls and Harlem Toile Chuck Taylors to honor Vice President Kamala Harris.

At Vanderbilt, I teach two courses on soul food. One of my missions as a teacher is to introduce my students to authors and visionaries I want to celebrate. An unexpected consequence is that sometimes my students discover new reasons to celebrate their own parents or their classmate’s parent. Over the years, more than a few of my students have had a parent who paid at least part of the student’s way through Vanderbilt while working in Southern food. I’ve taught a student whose parent owned a food truck, one whose father catered to men working off oil rigs when they were back on shore, one whose family owned an African-Caribbean restaurant in New York, and others. These are a few of the authors who helped my students contextualize and exalt the art and craft of cooking down South, up South, and west South: Rufus Estes, Edna Lewis, Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor, Freda DeKnight, Norma Jean and Carole Darden, Maya Angelou, Michael Twitty, Bryant Terry, Jessica B. Harris, Caroline Randall Williams, Anne Bower, John Egerton, Toni Tipton-Martin, Adrian Miller, John T. Edge, Francis Lam, Julia Reed (for a complicated article on B. Smith), Randall Kenan, and Kevin Young.

In her poem “That Soul Food’s on My Mind,” Tarfia Faizullah dreams of setting a “sumptuous seasonal table” for a “leisurely supper” with loved ones. As I write, COVID numbers are rising daily and such a meal is depressingly out of the question. Perhaps this issue can serve as its own kind of leisurely supper, with each offering its own considered course.

To begin, Crystal Wilkinson gives us a powerful memoir of grocery procurement in Kentucky during the pandemic. How many of us can say, “We still have cans of food that we can no longer identify because the labels have been destroyed from washing too much”? I can. How many of us know like Wilkinson that the strange gift of COVID has been that we cook better now because we have begun cooking so much more than before? I will be cooking her recipe for tomato soup soon.

Too many in COVID times are drinking too much. Julia Bainbridge provides us a recipe for a very sophisticated Southern whole-tini—which she claims tastes a bit like North Carolina. The recipe for Maitake Mushroom Tea is reason enough to buy this magazine.

You may not know it, but pimento cheese provides a window into understanding the interplay between race-based Southern labor discrimination and evolving Southern class distinctions—read Cynthia’s R. Greenlee’s “Pimento-cracy” to get the view.

Mark Powell’s “After Apple Picking” shows how changing labor conditions and climate change led to the decline of the South Carolina apple industry.

Amanda Little, known for The Fate of Food, weighs in reporting on the historic theft of Black farmland. My daughter Caroline Randall Williams offers “A Sustainable Call and Response.”

In “The Art of Being Eaten Alive,” Channing Gerard Joseph provides us with a brilliantly brief meditation on the genius embodied in an iconic plantation dance. If this were not feat and feast enough, Joseph engages dance, poetry, and food along with a large and transatlantic world, reframing Frederick Douglass by calling in his most radical observations about what some people will eat.

Ashanté M. Reese searches for sweetness in an anti-Black world and walks us through the fraught history of the Imperial Sugar Company, reflecting on the interplay of “life and death, mourning and celebration, past and present” as she makes an offering to the dead.

And with his short story “Flashlight,” J. Shores-Argüello reminds us that the back porch of the South slips far down to include the location of this story, Costa Rica. A ghost story based on real events, “Flashlight” was inspired by the last time the author made an olla de carne, “a confluence of short rib, chayote, yucca, and plantain.” As Shores-Argüello writes, “Like most Costa Rican food, it featured subtle ingredients, magic hidden in the technique.”

Food has the capacity to address all five senses. The art in this issue was chosen to celebrate the ways in which foodstuffs, individual dishes, and whole tables delight and surprise the eye—as well as the tongue. COVID has (temporarily or permanently) stolen from so many the ability to taste and smell. These images are offered into this moment and into the larger history of the down South, up South, and west South table as both a gesture of mourning for what has been lost, and as a salute to what abides, what persists, despite.

Black Lives Matter. Say Her Name. Sedition. These seven words, one for each day of the week, were the words high in my mind as we worked on this issue in January. Reckoning comes before reconciliation and often begins at the table. Reading the getting-to-final drafts of the articles and stories and poems in this issue, I was astounded to discover, one more time, how the sweetness of the table can ease our most bitter hour. There is joy in that. And joy for the table is where art and history enter our bodies and through our bodies our lives, through food and conversation.

One of my very favorite spirituals is “Welcome Table.” It’s a wonderful song about the power of telling your story over milk and honey. Talk and food. Bring the good food and invite the conversations that change things for the better. It’s hard to lie with a mouth that has been well fed.

The writers in this issue have been extremely well fed. They have tasted straight from the pot with a clean tasting spoon. They tell the truth and bring the good recipe.