Erosion

By Jeanie Riess

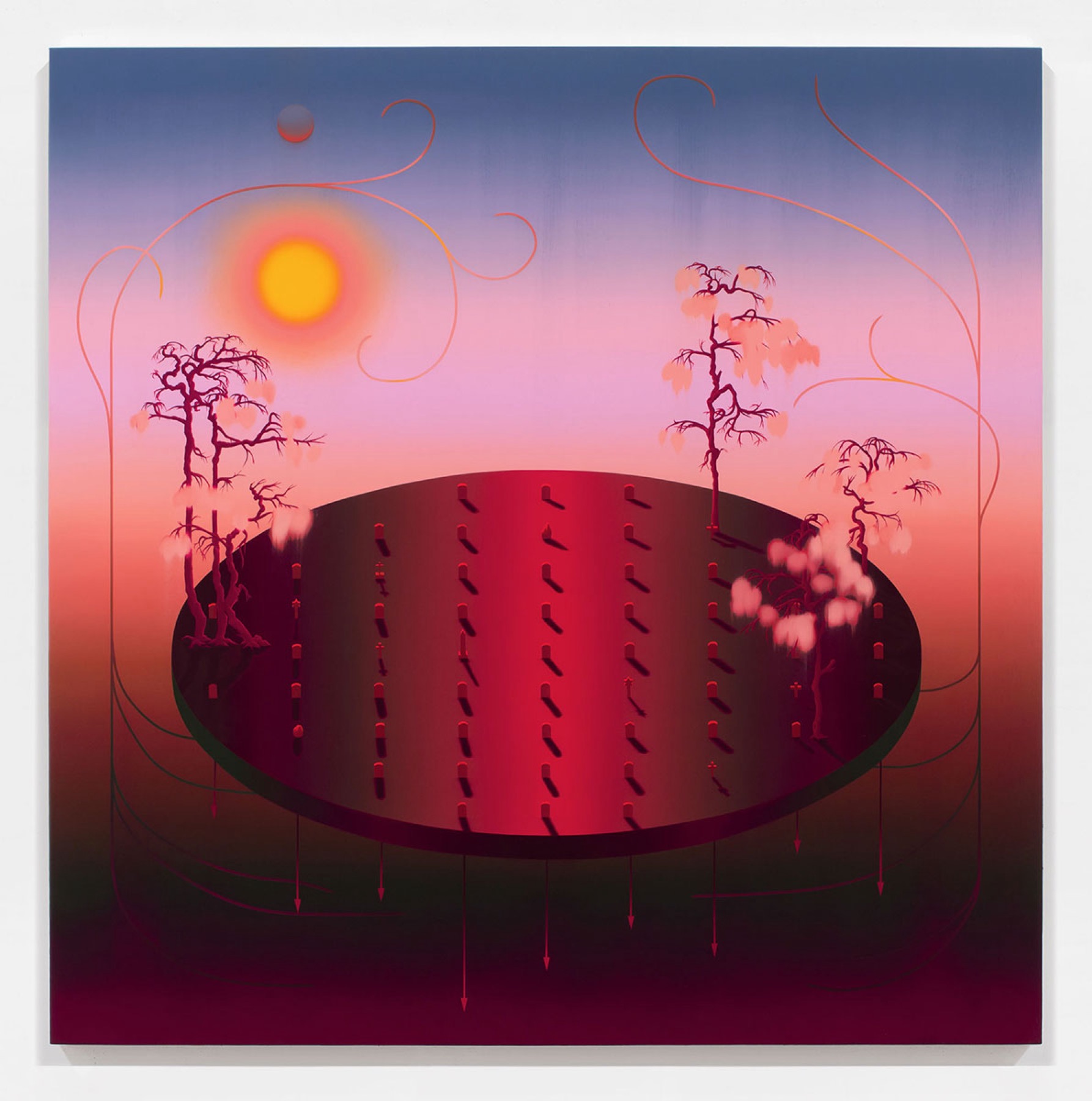

"Drift," oil and acrylic on canvas, by Nicolas Grenier ©The artist. Courtesy Luis De Jesus Los Angeles.

My dad was a trial attorney in New Orleans. When my brothers and I were little, we thought he was Mozart. Every night, he played classical music so loudly that the walls of our house shook. He sat in the living room and smoked a cigar. He had wispy gray hair that stood up in a breeze. He wrote poetry about riding the streetcar with his grandmother. When he passed a police officer, he tugged his seatbelt and held the clip at the buckle. He let the seatbelt go the minute the officer was out of sight.

***

In second grade, our teacher took my class to Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve. It was a fall day, sunny and cold, and cypress trees towered over us. Their knees peered out of the water. The girls in my class were singing a pop song. They all knew the dance moves to it, but I’d never even heard the song before. Our teacher said, “Can you believe you have all this nature in your own backyard?” We saw an alligator glide through the water. In fourth grade, my teacher told us not to stand in front of the refrigerator with the door open, to know what we wanted before opening it. She told us that if we only had to go a short distance, we shouldn’t drive; we should walk. She told us that in a greenhouse, the heat gets trapped by the glass, and that the same thing was happening in our sky. She told us that hairspray made holes in the ozone layer.

***

I begged my dad to wear his seatbelt and I wished that he would drive less.

***

Jean Lafitte was a pirate who, with the help of his brother, Pierre, smuggled stolen goods and enslaved people to and from merchants and households in New Orleans by way of the Gulf of Mexico in the early 1800s. Pierre maintained contacts in the city, while Jean tended the port and the open water. He spent most of his time in the Gulf. The port that the Brothers Lafitte established was right near Grand Isle, where Edna Pontellier, the protagonist of The Awakening, drowned herself more than half a century later.

***

Many critics call Edna Pontellier’s suicide by drowning an “escape.” From an affair that would never work out, from the patriarchal powers that ruled her life in New Orleans, from the duties of motherhood she’d grown to resent as they confined her and kept her from self-actualization. And maybe, at some point, the Gulf of Mexico did feel like an escape, not only for people wanting to drown but for people wanting to go places—the water as conduit to land far and near. But as the water gets higher, the Gulf of Mexico is not an escape. It’s a threat. It breeds hurricanes and laps farther up the shore each day.

***

In 1815, Jean and Pierre fought alongside Andrew Jackson in the Battle of New Orleans. President James Madison pardoned the brothers for their piracy. They became heroes, and everything in New Orleans is named after them. The oldest bar in the city, famous for its sludgy, purple frozen daiquiri, is called Jean Lafitte’s Blacksmith Shop. I am a descendant of Jean Lafitte.

***

I grew up swimming in the Gulf. I didn’t know it was warm, because I never swam in any other body of water. I didn’t know that the water was murky and brown; I thought that was just what water looked like. Everything I ate as a child came from the Gulf. Fried shrimp po’boys after soccer practice and sandy, lukewarm oysters before Christmas dinner.

***

Industrial plants line the Mississippi River from Baton Rouge to New Orleans, numbering about one hundred and fifty total. This area is known as Cancer Alley. You are seven hundred times more likely to get cancer from air pollution in St. John the Baptist Parish than you are anywhere else in the United States of America.

In 1969, DuPont built a neoprene manufacturing plant in St. John the Baptist Parish. Looking at where the plant is located on a map, I imagine its proximity to Lake Pontchartrain, where my mom grew up swimming.

Breast cancer doesn’t run in our family, but when I was nine my mom was diagnosed with it anyway.

***

My mom died. My dad loved us. He cooked us elaborate meals that took three hours to make and fifteen minutes to eat. We said prayers every night for the people we knew: “And God bless Sarah Beth, for sharing her string cheese.” We rarely went to the dentist. We went to summer camp, but our enrollment was delayed because no one had filled out the paperwork. My dad couldn’t keep still. He left us. To go to New York, to hear the Brandenburg Concertos performed on the instruments that Bach would have used. To go skiing in Santa Fe. To go to the office. He went to Galatoire’s with clients. He ate bread pudding at the Bon Ton. When he got a cellphone, he kept it turned off.

When I was ten, my dad gave up hard liquor. He bought a wine cabinet that controlled the temperature on expensive bottles of wine. He worried about money. A few months later, he started drinking hard liquor again. He got a business card printed with the specific and very cumbersome way he liked his martini prepared. Hendrick’s gin, stirred, olives and a twist.

***

Right before my mom died, I asked her if she believed in Santa Claus. I knew better than to ask her more directly whether Santa Claus existed. “Do you think you can believe in something and know it’s not real?” she asked me. I was nine years old and I answered timidly. “Yes,” I said. She nodded. “Then that’s how I feel about Santa Claus,” she said. And she left it at that.

For people in Louisiana, it’s the opposite: you can know that something is real and not believe in it.

***

In fifth grade, my class helped load old Christmas trees onto a truck. Then we followed the trees to the swamp. We watched men unload the trees and lay them down in the marshy areas of the swamp. The hope wasn’t to make them grow. The hope was that the dead trees would stop the water from taking more and more Louisiana soil.

When I was twelve, it was so cold it almost snowed on Christmas.

When I was thirteen, it was seventy-five degrees on Christmas.

In eighth grade, my science teacher made us write down everything our family threw away. I taped a sheet with a pen above the kitchen trashcan. Someone, my dad or one of my brothers, threw the sheet away. (Probably by accident, but one of them did throw it away.)

***

My dad could do amazing things with a fish. For redfish court bouillon, he set the flame very low and simmered the fish. At oyster bars, he used to make a deal with the oyster shucker: “If you shuck ’em and give ’em right to me, I’ll pay you directly.”

***

When I was in high school, my teacher made us test the water in the Audubon Park lagoon, the Mississippi River, and Bayou St. John. We found alarming amounts of nitrates, from fertilizer, and coliform bacteria, from dog shit.

***

My dad was one of the best storytellers I’ve ever known. Once, he told a story about a summer job he’d had driving a dump truck. He dropped the contents of the dump truck onto the car behind him. It turned out that the person who’d been driving that car was in the room when he told the story. “You son of a bitch,” the man said, smiling.

My dad remembered everything that had ever happened to him. He remembered every detail. He remembered how New Orleans was, what it felt like. He said the women used to trade recipes from their porches. He said they never used air conditioning when he was a kid. He remembered hot peppers growing like weeds on the sidewalk. He used to rub them and then rub his eyes to make himself cry. He ran away from home. He put his brother in a trashcan and rolled him down the stairs. There were half as many oil refineries. No, a quarter as many.

***

In City Park, they used to set up an ice-skating rink for the winter. They served hot chocolate that never cooled off because it was hot outside. The rink had puddles in it. But my dad could skate. He could spin and go backwards and go very, very fast. It was almost more fun to watch him skate, there among the puddles, than it was to skate myself.

Still, I wore a parka from the Gap, imagining myself in the vein of the Mighty Ducks, imagining what it was like to live somewhere else.

***

After Katrina, my dad broke into the city before it was open. He said the trees looked like a giant had taken them out of the ground, shaken them, then replanted them. That’s what I told everyone where I had evacuated. That the trees had all been shaken.

My dad lived in our house without power.

***

CNN asked why on earth anyone should rebuild New Orleans.

I spent the beginning of my junior year of high school at a prep school in New York City. Why, the girls in my class asked, had I transferred junior year? They hadn’t heard of the hurricane yet. But I didn’t mind. I was relieved they weren’t asking me why I would live in a city that was below sea level.

Every day during study hall, I left. I became friendly with the security guards who stood outside of the school. They loved New York so much, and they tried to get me to understand and to love it too and to be less sad. When I left New York a few months later to return home, the security guards gave me a Yankees bomber jacket and a Yankees Christmas tree ornament. I wore the bomber jacket on the plane ride home. But no one was asking whether we should rebuild New York City.

When I came home, it looked like a hurricane and it smelled like a hurricane, but the flood lines showed that it wasn’t just a hurricane. The ice cream parlor in our neighborhood had a plaque made to show where the Katrina water line was. Standing next to it, it came up to my ribcage.

***

When I was getting ready to go to college, my dad stopped leaving. But it was too late. He was sad and he drove me all the way to Ohio. In the passenger’s seat, I listened to my iPod the whole time. With headphones.

In college, I learned to cook because I was homesick. On the phone with my dad, I’d ask him to give me recipes. I wrote them down with a pen, right into my political science textbook. Red beans and red-eye gravy and some version of gumbo without the fillet and without seafood.

It was hard to find fish in Ohio. Also hard to find: ham hock.

***

When I flew home from college my freshman year and the plane started descending over the swamps, I imagined the leftover tinsel on the dead Christmas trees from the window. Over a pile of boiled shrimp at Middendorf’s, on the lake, my dad said, “This is heaven. And you’re living in hell.”

I realized that the potholes I’d been swerving around the entire visit home weren’t from big trucks. They were from the land sinking into the ocean. I went back to school and decided that I hated a.) the South and b.) driving.

***

My dad joined the senior swim team and fell in love with a woman he met at the pool.

In winter, when my dad felt a cold coming on, he made himself a “scotch snowball”: A glass of crushed ice with scotch on top.

My dad published four poems in a journal and got another business card. It said, POET. AVAILABLE FOR READINGS AT MODEST RATES. NO CROWD TOO SMALL.

***

My college roommate came home with me to New Orleans and fell in love with the palmettos and the outdoor bars and the possums high-wiring over tables of people dining al fresco. She was ready to move to New Orleans until she saw a popsicle cart in the French Quarter that she said boasted it had been in business since 1897. She didn’t think she could make her own life in a city so obsessed with itself and being old. It was too established for her, she said. She couldn’t evolve. She felt the weight of its history. I wasn’t offended by this. I knew exactly what she meant.

***

The news speculated what would happen if another Katrina hit New Orleans. Some people said that New Orleans wouldn’t exist in fifty years. Decades prior, the Army Corps of Engineers had started diverting thirty percent of the Mississippi River down the Atchafalaya River. Flood the swamps instead of the city. Save the city. Too late to save both.

***

In 2010, the explosion of the Deepwater Horizon oil rig caused the Macondo Prospect to spill out around 4.9 million barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico. Four years later, the amberjacks, a large reef fish found in the Gulf, were still deformed. My dad wrote a poem about the BP oil spill. He named the poem “Macondo,” after the oil prospect, which itself shared a name with the fictional town in Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude.

One Hundred Years of Solitude was my mom’s favorite book.

***

After college, I was a newspaper reporter in Mississippi. One night, in New Orleans, my dad was drinking and fell down the stairs and hit the back of his head. His brain got pushed forward against the front of his skull. He went to the ICU. When he got out, he called everyone the wrong name. I moved back home. The winters were hot.

***

Grand Isle is a strip of land so thin that as you walk along it you can see the water on both sides of you. Once there were summer resorts, lively fishing camps, and dunes with sea grass. Now there are houses on stilts, sand, and water.

The Awakening is set in Grand Isle. It’s a good thing that book exists because Grand Isle barely does.

***

Local newspapers and national magazines and people on the street and politicians all started repeating the same phrase: Louisiana loses a football field of land every hour.

***

My dad told me he was reading a book about coastal land loss, but when I asked him what he’d learned he couldn’t think of a single thing. He gave up drinking and stuck to it this time. But it was too late. He stopped remembering things. He stopped telling stories. He couldn’t get out of bed. He stopped cooking. He stopped writing poetry.

***

Sometimes I imagine the football field at my school, bright green with white stripes and numbers, washing away. And then washing away again. And then washing away again. I turn the sink off while I brush my teeth. I ride my bike. But it’s too late.

***

I imagine my dad’s brain out there with the cypress knees. The water keeps coming up and up and up.

***

During the pandemic, I had a baby and I named her after my mother, who’d been named after her mother, who’d been named after hers. Her face is so beautiful, and she doesn’t know what we’ve done. I think about having to tell her how responsible I am. For liking the things I was supposed to like. Nothing old, everything new. Travel. Moving. Packages delivered overnight. I liked shampoo, conditioner, soap, body wash, face wash, the kind with the plastic beads in them. The kind that ended up in fish. I liked lotion, nail polish, nail polish remover. I liked building things and tearing them down, liked motorboats skipping across the water, hot baths kept hot by letting some water out and putting more in, to-go food, to-go drinks, to-go everything. Powdered hot chocolate in a Styrofoam cup on a cold day. I liked keeping roaches away. Keeping ticks off the dog. I liked the dog.

One day I will have to tell her how complicated it was. To hate all of humanity, to hate ourselves, but to love people, to love each other.

***

In 2020, Louisiana had the greatest number of named storms since official records began in 1851. The Christmas trees didn’t help; in 2020, a study found that it was too late to stop coastal land loss. The state is investing in mass relocation programs for people who live in flood-prone areas. It’s exploring the possibility of floating schools.

***

People will forget what it was like here. It’s not just my dad. People will forget, and die, and with the land disappearing, there are fewer and fewer records of what was once here. It can’t be written in the sand anymore. And most of it is too magical to believe, anyway.

No one believes this, but when I was young we used to ride the elephants at the Audubon Zoo. They must have shut it down because it was a dangerous thing to do, but even after they shut the elephant rides down, you could still ride the camels. And we did, until that was shut down too. But no one believes we rode camels in New Orleans, either. It’s just memory. And how much is memory really worth if it can disappear so easily?

***

And now when I need a recipe for gumbo, I ask the internet.

This piece was published with support from The Julia Child Foundation for Gastronomy and the Culinary Arts.