Snugfit Eye Patch

By James Seay

Photograph courtesy the author

Othello to Iago on Desdemona’s handkerchief:

…give me the ocular proof…

Make me to see’t...

Othello, Act III

When I arrived home following a weekend camping trip, my mother’s welcoming smile vanished in a look of concern, and she told me that my eye was crossed. She meant my artificial eye. I had lost my right eye the year before, at age twelve, while visiting my grandparents in Senatobia, Mississippi. A rock flew up from the open chute of a lawn mower. “Got it knocked out,” as my male friends described it. Looking in the mirror after my mother informed me of the canted eye, I saw that the prosthesis was pointed outward, suggesting both quandary and alertness toward that side of the world to which I was blind.

What had happened was that on the camping trip I had wiped the sleep from that eye and in the process had turned it in its socket. Having only the small creek beside our tent as a source of reflection, I did not know the eye was turned. Nor did my fellow Boy Scout campers tell me. Perhaps they were sparing me embarrassment. Maybe the eye awoke in them a kindness, with which we normally were awkward. There was the possibility also that they considered the eye off limits, taboo.

One of the mothers fetched us from the rendezvous point of our camping trip to drive us home. Seated beside me in the backseat of the car was the mother’s daughter Martha, along for the ride. I had a crush on her, though not one that I had announced—or fully understood. She had on shorts, and there were hairs on the tops of her thighs; she was barely pubescent. A film of perspiration glistened lightly above her upper lip. The nearness of all that—Martha herself, her bare legs, the delicate hair, the perspiration—set off stirrings of attraction I had not known before. She did not mention my crossed eye, nor afterward did she ever greet me with anything other than a conventional cheeriness.

That experience on the camping trip and with Martha in the backseat, and its various iterations—insecurity with girls when I was young, embarrassment at compromised depth perception, assignment to a vague status of being different, and so on—led to my decision to give up the fake eye and wear an eye patch. A kind of transformation. There is hyperbole in that notion, but I cannot overstate the degree of my sensitivity, my self-consciousness, in the face of what seemed to me an attention—implacable at times, subtle at best—focused on the motionless eye. And the feeling that half of my countenance, that which the eye gave back to the world, was misleading and insufficient. You could question the logic of my decision and suggest that a patch invites even more attention. True, but the patch presents a decidedly different and, for me, more comfortable visage than I could find otherwise. There is also the fact that logic had little or no governance in my mind, vexed as it was by memories of embarrassments, represented early on by the image I had formed of my crossed eye fixed on the periphery of the campsite as though searching for what friends alongside the creek were seeing straight on. And of Martha in the backseat.

And so, years later, when I entered graduate school, where I knew not a soul, I sewed an elastic band on a crude black patch and bound it around my head. I then opened the door to my dorm room to present my transformed and openly monocular self to the world. In the walk to my classroom, I had a feeling, new to me, both of freedom and utter uncertainty. Mine was nothing like, say, a war wound, though I can empathize with the veteran strapping on a prosthetic arm or leg for the first time and walking out of the clinic. Part of that type of long walk is accepting that people will notice while hoping that the agency of substitution and one’s adjusted identity will in time render their gaze neutral, harmless.

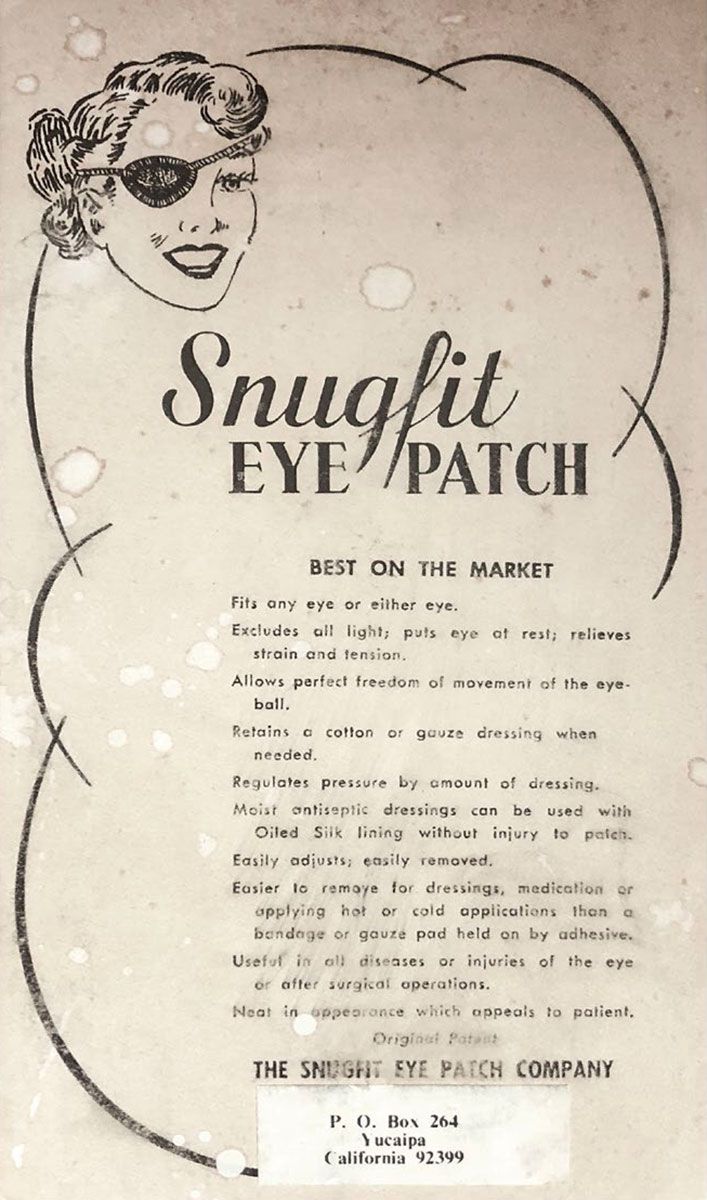

All of this, at graduate school and later at home, was in the mid-1960s, and there was no internet to search for suppliers of eye patches. I inquired of an optometrist regarding possible sources, and he gave me the address of a supplier in California, Snugfit Eye Patch Company. I ordered a trial patch. It was far superior to the patches one finds in the eye section of the first aid shelf of drug stores. In fact, so keen was my anxiety over the possibility of ever having to go back to that shelf, I ordered a lifetime supply of black eye patches from Snugfit. Two boxes full, a single box now remaining, yellowed with age. It features as illustration an attractive woman with the Snugfit eye patch. She is coifed in a 1940s hairdo. Which would seem to compromise the breakaway gender spin they have put on things—avoiding any hint of the male stereotype such as the suave bepatched Hathaway Man in the shirt ads of the mid-twentieth century. But she is smiling, an open summons to our gaze, and that assurance and candor continue to set off a ripple of bonhomie in me, the target audience.

So far as I can determine, the Snugfit Eye Patch Company no longer exists. They were in Yucaipa, California. The post office box is listed on a small label that has been pasted over a former address on the Snugfit box. At the time of my writing, Snugfit Eye Patch Company was listed online, but the Yucaipa Chamber of Commerce had no entry for it. There was yet another Snugfit Eye Patch Company listed online for Green Bay, Wisconsin. Not that I planned to order any more eye patches, but out of curiosity I called the phone number. It was no longer in service. The great Snugfit mystery.

There are ample sources, though, if you need an eye patch. As for selection, you can get a hot pink eye patch, a hot pink camo eye patch, or a standard army camo eye patch. Also, an American flag eye patch. One company offers a cryptic two-pack, a red wagon on one patch, a yellow backhoe on the other. And there is a black eye patch that, in the spirit of Halloween, carries a skull and crossbones. All of which is to say that I am not alone in having sought out a patch for my needs.

My graduate school days coincided with the escalation of American troops in Vietnam. In 1966 the draft call was the highest since the Korean War. The year prior I had received notice from the Selective Service System that my student status exempted me from the draft and my classification had been changed to II-S, exemption as a student.

My classifications leading up to this event make a convoluted story. Following my registration with the Selective Service System in 1957, I was classified IV-F, owing to the loss of my eye, and not qualified for military service. But I wrote my local Selective Service board with a petition not to be classified IV-F.

My father had served in the First Marine Division in World War II, surviving the Peleliu and Okinawa invasions, two of the most savage battles of the war. One of his fellow platoon members later informed me that his division received a Presidential Unit Citation for each of those battles. My father did not bring his medals or citations home, nor when I was young did he ever talk to me of his war experiences. I had always had an awareness of the dangers he faced and survived, and I realize now that in writing my letter of appeal in 1957 for classification other than IV-F, well before I knew of the Presidential Unit Citations, I was guided by the sense that I needed to take his example of service as a model.

My letter, though, was a model of the sophomoric. I had a sense of duty to country, but the letter was informed mainly by my father’s influence in my life. Not that our relationship was always one of harmony, nor am I any kind of superpatriot. Incidentally, in seeming contradiction to my earlier request for military service qualification, I marched against the Vietnam War in 1970.

In petitioning for the revocation of the IV-F classification in 1957, my recollection is that I laid out my bona fides with a zeal that is unavailable to me now yet remains heartening in its testimony to the ingenuousness and passion of intent that one can call forth as a youth. I opened my bid with the insistence that the “A” I had earned in the wrestling portion of a physical education course was incontestable proof of my fitness for the demands of military service. Next, I listed the high school sports I had participated in, with attention to the medals won in track and field. I added Boy Scout merit badges and camping expeditions. As for leadership potential, I was student body president in high school, and voted Best All Around in the superlatives. The list goes on. I ended up with a I-Y, not a IV-F, meaning I was thus qualified for service in a national emergency or time of war.

Though there were many citizens during WWII with legitimate reasons for a IV-F classification, it nonetheless carried a stigma, and the term “draft dodger” came to be associated with the IV-F classification. Even at a young age I was aware of this negative characterization. And when I opened that first letter from the local board of the Selective Service System, I felt the full burn of that stigma.

The clerk who signed my original notification card was our next-door neighbor, and I was dating her daughter off and on, with hopes for more on. Her daughter knew of my eye, but the card her mother signed, which was apparently discussed in their household, became a kind of quarantine placard. No chilliness on the daughter’s part, certainly no animus, but a halt to any romantic progress. Palimpsest of the half-forced cheeriness that Martha beamed at me in school hallways following my backseat sideshow after the camping trip.

This accounting of my father’s military service and my efforts to get my classification changed goes to a truth about one’s sense of manhood, a truth not limited to my own generation: that one is somehow inadequate, incomplete, less a man, when one loses a part of the body, whether a limb, an eye, or a loss that results in disfigurement. (I am sure there are equivalent forces shaping a young person’s sense of womanhood or femininity as well, but that is outside my focus here.)

This can be particularly acute in a young man’s need for a father’s approval. Or his perception of how he fulfills or fails his father’s expectations. My own father spent his whole life striving to fit the image of manhood—work hard, show no emotion, be brave, be proud, man up—that his father put before him. Which is what my father in turn put before me. For instance, I have a letter of reminiscence and updates written to my father’s platoon members by a fellow platoon member, Jack “Tex” Price, who visited my father after the war: I reminded him how tough he was on us, but also told him I appreciated it. He helped most of us get back, where some would not, had he not been around.

I wanted to be like my father. But after the loss of my eye, I sensed that his attitude toward me shifted, that he no longer saw me as a son who would be able to fit his concept of manliness. Not that he was cruel or remonstrative, just that he did not seem to look on me in the same manner as before my loss. He was protective of me, though—perhaps to a fault. He wanted to keep me out of further harm’s way. My mother was protective also, but her faith in me remained steadfast.

It was not until my teenage years that my father, perhaps at my mother’s urging, began to include me in more of his activities—fishing, going out at night to farm ponds with our carbide lamps atop our heads to gig frogs, dressing the frog legs out for my mother to fry. In teaching me to drive our Chevrolet Bel Air, not only did he have to reach over and help me turn corners, I also consistently stalled the car when I let out the clutch. It was during this time that we moved from Mississippi to south Florida, and instead of continuing with the Bel Air, he put me on a bulldozer and turned me loose on a vast open field where he was supervisor of development for farmland. Not much chance of crashing into anything, and a simple clutch maneuver. It was then that his attitude toward me shifted toward approval. I would take the bulldozer out with a Bahamian named Desmond and we would work all day bulldozing brush, pushing it into a pile, dousing it with a mix of gasoline and diesel fuel, and setting it aflame. Woosh. Work. No thought of being one-eyed.

Sometimes on weekends my father and I would drive from our home in Pahokee to Port Salerno to fish with our neighbor Bill Jones on his thirty-foot power boat Vergie. Well out of sight of land, and with no sonar fish-finder, we would drop cut bait into the depths of the Atlantic and hope we were over fish. Usually, we had a good catch of grouper and red snapper to take home. I was not invited along every Sunday they went out, and when I was I usually got seasick. My father, meaning well, would give me saltine crackers and send me below to a bunk, not realizing that the diesel fumes in the small cabin added to my wretchedness. All the while, he was on the deck above pulling in fish, whooping and hollering with Bill Jones, drinking beer—free of the savagery and ash of the war that he had emerged from, unscathed except for a piece of shrapnel that he still carried.

My father’s exuberance on the water informs my fishing today. But there are challenges with monocular vision that I find more pronounced as I age. Owing to the lack of sight on one side, I am hampered in my casting with both fly rod and spinning rig, fearful of hooking the angler next to me, especially in the tight space of a drift boat. Or in any boat where two or three fellow anglers are lined up casting into the same space of water. At times I have requested the outside position, with no angler on my blind side. One of my pals half-jokingly says I am trying to play the one-eyed card. Sometimes he yields, sometimes not. We banter back and forth. My friends, all in all, take me pretty much as I present myself, and the subject of my vision rarely comes up. And when it does, the tenor is usually ironic or that of playful humor. Which is fine by me.

One thing that confounds me, though, is when a stranger, outright or early on in conversation, brings up my patch or wants to know what happened to my eye. I am civil, but brief, in my response. Typically I ask if a family member or friend has a similar condition, is that why they have inquired? Almost without fail I know immediately that any potential for further relationship with that person is less than zero. A notable exception is the time a man standing in front of me in a line at the Barcelona airport turned and asked about my eye. Before I could give my customary reply, he hastened to explain that he was an ophthalmologist and had a particular interest in monocular vision. A boarding line in Barcelona. An ophthalmologist. With an interest in monocular vision. ¡Dios mío!

Ruskin tells us, “The greatest thing a human soul ever does in this world is to see something, and tell what it saw in a plain way.” This speaks to the primacy of vision among the senses. If Othello can see Desdemona’s handkerchief, have the ocular proof, he will know Desdemona has been untrue. Or so Iago would have him believe. Shakespeare puts a spin on the notion of vision and its privilege in our sense of the world when Lear beseeches blind Gloucester on the storm-ravaged heath:

O, ho, are you there with me? No eyes in your head…. Yet you see how this world goes.

To which Gloucester replies:

I see it feelingly.

It would be dumb and ungracious of me to try to appropriate Shakespeare’s trope of seeing, understanding how the world goes. In full blindness. I see it feelingly. Nor would I try to halve the trope—half feelingly. Best to say, I see it differently. Snugly fitted.