The Spirit of the Bend

By Jarrett Van Meter

Illustration by Miranda Bruce

The stark scenery felt at odds with my excitement, a moment of great personal anticipation set against a vast and unoccupied canvas in the belly of the country. There is no state line sign on the way in, but Kentucky begins where the dual meridian stripes of Tennessee State Road 22 melt away, the brown pavement darkens to black, and the name becomes Kentucky Bend Road on the GPS. Behind me: a tennessee state line sign—green, riddled with bullet holes, pronounced against the empty fields and clear February sky behind it. I had made it to Kentucky Bend, the forgotten outpost of my home state, a place I had only learned of two months prior. Three dogs, two friendly pit mixes and a Chihuahua mix, trotted up to greet my truck like a state-appointed welcoming party.

I first learned of Kentucky Bend while visiting my father for Christmas. Flipping through a state road atlas in his Lexington condo, he pointed to the small piece at the bottom left of the page. In 2004, the state adopted the slogan “Unbridled Spirit” for promotional use on, among other things, government stationery and license plates. But those were just words. Here it was in essence: a piece of the Commonwealth that had jumped the fence and was running loose on the other side of the state line. In February, as soon as my schedule allowed it, I packed my suitcase, my dog, and my bicycle into my pickup and headed seven hours west from my home in Asheville, North Carolina, to the Bend for a reunion beyond the pasture, a backdoor homecoming.

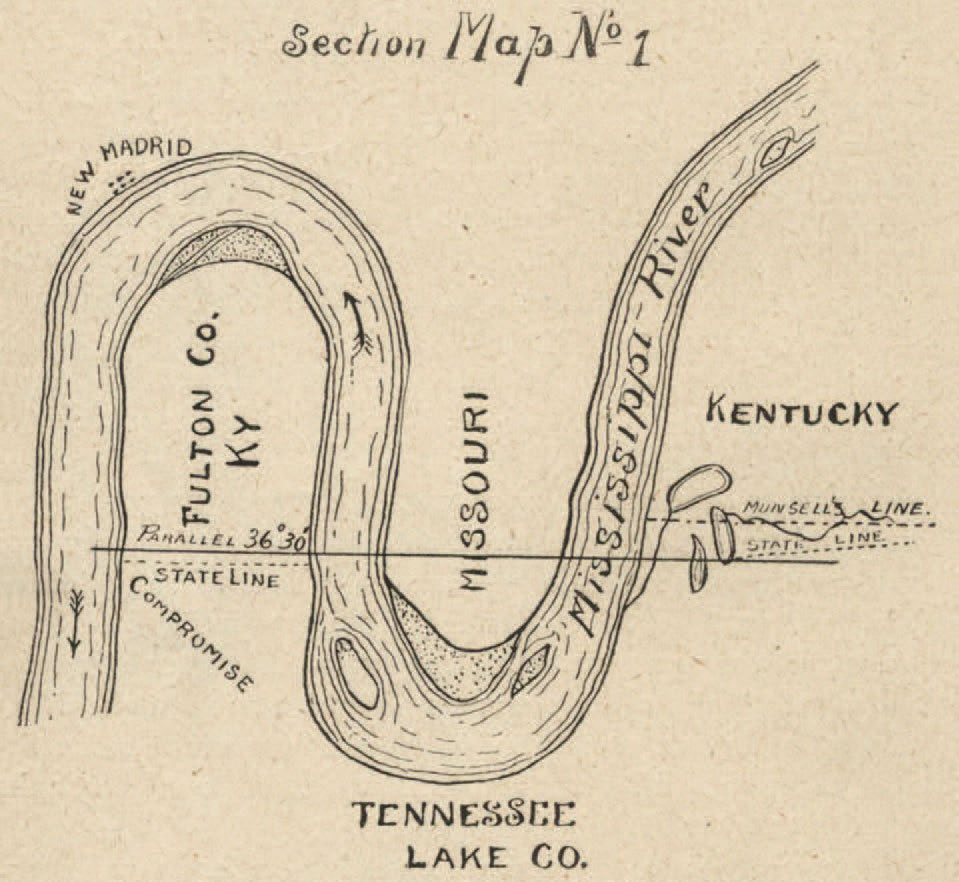

The Bend is geographically removed from the rest of the state. Its oxbow shape is a result of three successive New Madrid earthquakes in late 1811 and early 1812. The earthquakes remain the most powerful to ever hit the United States east of the Rockies—strong enough to change the course of the Mississippi River. The Bend is plainly visible on the statewide maps that actually include it. If you were to pick up Fulton County, the state’s westernmost county, between your fingers and flip the state over, as if turning back a page in a book, Kentucky Bend would look like the period punctuating the state of Kentucky. It’s Kentucky’s Hawaii. Or rather, it is Guam: an association in name more so than spirit.

I read everything I could find about the place: from Mark Twain’s account in Life on the Mississippi, published in 1883, to a 1972 New York Times article, to one Associated Press writer’s account from 2002. All of the stories seemed to look backward, into the history and lore of this geographic oddity. Then I checked census data. The 2020 census put the population of the Bend at just nine, half the number from 2010. I decided to go while there were still people, while it still held Kentucky culture, whatever that might look like. I needed an introduction while it was still running, while there were still grains in the hourglass: stories, voices, and spirit.

Pete Morgan is the Fulton County property value administrator, or PVA, a locally elected official tasked with the assessment and appraisal of all property that lies within the county. Morgan usually makes the four-and-a-half-hour drive from Hickman to Frankfort, the state’s capital city, once a month for business in the Kentucky Association of Counties (KACo) building. The building has long rows of windows stemming out from a pillared entryway. Just inside the main door, in the front atrium, a giant map of the state is etched into the floor.

Morgan stops here on every visit, admiring the network of one hundred and twenty counties that make up the state’s forty thousand square miles. His eyes always pan to the left, down and out to the tip, to the county that looks like the silhouette of a sneaker: Fulton County. The rendering bothers him. While the map is largely accurate, his county is missing something.

“I always want to take a marker and draw it on there,” he said.

I met Morgan at Discovery Park of America, a museum roughly forty-five minutes east of the Bend in Union City, Tennessee. He wanted me to see the earthquake simulator, which replicates the New Madrid quakes responsible for the Bend’s formation. The Bend has become an obsession of sorts for Morgan. Last year, he was named the state’s PVA of the Year. Introducing him at the award dinner, Jonathan Bruer, the PVA of nearby Carlisle County, said, “If you spend more than five minutes with Pete, he will mention Kentucky Bend.”

Once you are looking for it, you will check every map, Morgan told me. The KACo floor map is missing its period, but so too are many maps and state renderings.

Even as the Bend’s population has dwindled from 332 at its height in 1880 to fifty in 1970 to just nine in 2020, its land mass is actually growing. Morgan loves that his county is the exception to the one constant of the PVA world: a county’s land mass. Upriver erosion, deposited via river dynamics, has resulted in the Bend alone adding seven hundred acres to Fulton County’s total area since Morgan took office in 2006. Fulton County soil. Kentucky soil.

“Once it starts growing reeds and willows and maintains that, even though it’s a sandy soil, it is taxable,” he explained.

Mark Twain said, “Buy land, they’re not making it anymore.” Except on the Bend.

When we reached the parking lot outside, I crouched down to examine the outline of Kentucky depicted on one of the state license plates. No dot. No Bend.

The nine current residents of the Bend belong to three families: the Whitsons, the Wilsons, and the Lynns. While mathematically this doesn’t bode well for natural accretion of population, it makes finding everyone easy.

The Whitsons live just over the Kentucky state line. It is their dogs that greet incoming cars. Winston Whitson is the patriarch, having lived on the Bend for all of his eighty years. The first house on the left belongs to him and his wife, Patricia. Their daughter, Leanne, lives across the road, in a small brick home previously occupied by Winston’s mother. The wood siding on the garage is a scar from tornado damage, and rusted out homestead equipment adorns both yards like garden statues.

From there the road runs taut-straight, cutting through acres of beautiful, vast, and rich farmland. On the right, just up the road from the Whitsons’ houses, a stone foundation that once held the house of Winston’s grandmother now sits like an empty stage. A bit farther, still less than half a mile into Kentucky, is the Whitson Cemetery. There are plenty of Whitson headstones—but also long-gone family names like Cross, Adams, and Speer—all contained by a short, chain-link fence.

Roy Wilson, Winston’s brother-in-law and neighbor, lives another quarter mile up the road with his brother, Marvin, and mother, Miss Daisy. Roy mows the cemetery’s grass, but mainly stays busy catching, cleaning, and dressing catfish from the mighty and feral Mississippi, which wraps around the Bend like a bonnet.

Just beyond the Wilsons’ is the road’s first fork. If you continue straight, the road turns to red-dirt gravel and meanders past ponds, bean fields, and the site of what residents still claim was the biggest cottonwood tree in the world, big enough for five men to wrap their arms around, fingertip to fingertip, before a bolt of lightning snapped it to a stump.

The pavement bears to the left, the road becoming Stepp Cr-426, named for the family that was once the largest landowner on the Bend. What was formerly Stepp land is now occupied by Donald Lynn and his wife and daughter.

From the driver’s seat of his black Cadillac, parked just inside the state line, Winston Whitson points to the pecan tree in his daughter Leanne’s front yard. The plot was once the location of the Bend’s only general store, owned and operated by Winston’s daddy, Joe. The building served as the Bend’s voting precinct, gossip center, and grocery. When Joe Whitson set up the first television in the shop, people gathered to watch wrestling matches.

Winston points out a sign that commemorates Compromise, the origin point of the 1858 state survey line that became the official boundary between Kentucky and Tennessee. It was also the name of the church split by the Watson-Darnell feud famously recounted by Mark Twain in Life on the Mississippi.

The decades succeeding Twain’s visit were boom years on the Bend. People like Donald Lynn’s grandfather and Daisy Wilson arrived to pick the abundant cotton. A new church was founded, then a school in the same building. Steamboats were the backbone of a thriving economy, hauling agricultural products and other cargo, as well as mail, up and down the river. A cotton gin opened, and a lumber and wood products company was established in the northern portion of the Bend. Ferry boats and other services associated with the busy river traffic sprung up.

Corn and wheat were the dominant crops on the Bend after the earthquakes, but cotton began to gain a foothold soon after the publication of Life on the Mississippi. By the turn of the century, nearly all the land was devoted to cotton, much under sharecropping and tenant farming arrangements. Neighbors picked cotton together, the cool water that bonneted the land a mere figment somewhere beyond the heat of the fields. The workers ate together: fish and game, preserves, and vegetables, garden-fresh and pickled. Relationships were formed, a sense of community fortified.

By the 1970s the growth of offshore cotton production began to drive domestic prices down. U.S. farmers, including those on the Bend, shifted their focus back to corn and soybeans. This return to grain production was accompanied by increased mechanization, leaving many of the farmhands without work. People began to leave the Bend. Today, Winston Whitson leases all of his property to other farmers who grow soybeans, corn, and wheat.

Pecan trees also grow here, and after shutting off the car, Winston walks me behind the house to show me his. His back porch is collapsed; his son ran into it with a tractor while mowing. It is February and the tree is bare, but the ground is speckled with pecans. He stoops over and grabs one, cracking the husk in a fluid, one-handed motion. “Real thin, the shell on these,” he says, popping the meat into his mouth and scanning the flat horizon. “Most of ’em is real hard.”

Then it’s time for me to leave so that Winston can head into Tennessee to get a prescription filled for his wife. Bend residents do most of their day-to-day shopping in Tennessee. They only travel to Hickman, the Fulton County seat, to register their cars, pay their taxes, and vote. Travel to the Kentucky mainland used to be commonplace. Adrienne Stepp taught school in Fulton City, and she and Barbara Lynn, Donald’s mother, would take trips to the bank every Thursday, making an afternoon of it by stopping for lunch at MeMaw’s Cafe, which, like many other shuttered Hickman businesses, fell victim to population decline in Fulton County.

Politicians, like former Fulton County clerk Betty Abernathy, used to routinely campaign on the Bend, but the number of possible votes is no longer worth the time and gas. Abernathy’s successor skipped the trip. Even Pete Morgan didn’t come during his first campaign. Now, according to Abernathy, many people in Fulton County aren’t even aware that the Bend exists at all.

“A lot of the residents of Hickman and Fulton and Cayce, the older ones are aware of the Bend and a lot of them have been down there, but the younger children, I doubt if they even have any idea if the Bend is even part of us,” Abernathy told me over lunch in Union City, Tennessee. “So really, the knowledge is not widespread that the Bend is even part of us, which is sad. It’s a beautiful area.”

The next day I stopped at the state line again, this time on my bicycle. The wind was powerful and it was at my back. I imagined the border like a starting line, counted down from three, and accelerated into Kentucky.

The fields began to blur around me. I was barely pedaling, but each pedal revolution seemed to add another mile per hour. Past the cemetery. Past the Wilsons’ place. I took my hands off the handlebars and extended them out beside me like wings. There were no cars; there would be no cars. The road was straight. No boundaries, no fences.

Instead of hooking left on the pavement I stayed straight on my runway, grabbing the handlebars as the pavement gave way to gravel. Even with gentle chop, the wind powered me north. The sky was vast, spreading far beyond the river’s boundary. A Kentucky terrarium.

I skidded to a stop at my turnaround point four miles later. My ears were ringing from the wind, my eyes blurry with tears. My heart was thumping and my cheeks sore from grinning. I checked my Strava app: I had been rolling at a speed of twenty-five miles per hour on perfectly flat ground. It was the ride of my life and nobody had seen it. Then it was time to head south, against the wind.

Map from "The American Historical Magazine" Vol. 6, No. 1 (January 1901), published by the Tennessee Historical Society

Daisy Wilson and her husband moved to the Bend in 1942 to pick soybeans and cotton. They leased roughly seventy acres and, like the Lynns, expected to inherit a piece of the land they had worked and called home for many years. But it was not to be.

Mr. Wilson passed away, and so did one of their children. Two sons went to work on riverboats and a few kids trickled into Tennessee. Her daughter Patricia married Winston Whitson and moved down the road. But Miss Daisy, now ninety, has never considered leaving. Despite coming up empty in inheritance, in the late seventies she bought a house and three acres of her own just up the road from the farm where she once worked. Two of her adult sons, Marvin and Roy, live with her in the modest, single-story home.

The church that doubled as a school was on the Wilsons’ land. Winston Whitson went to school there, as did Roy Wilson and his siblings before the building burned down. The State of Kentucky now foots the bill for the education of Bend residents in Tennessee schools. This arrangement saves unruly bus trips for state employees and long, ragged days for commuting students. An old red pickup now occupies the space next to the road where the schoolhouse once stood.

Like at the Whitson compound, a pit bull mix greets me in the Wilson driveway. The yard is a gallery of equipment, sheds, and clutter. Roy’s fourteen-foot, camo-colored fishing boat and trailer, parked behind the house, is carpeted with sticks, debris, and weathered flotation devices. He occasionally fishes from shore but prefers to take his boat. He brings food with him, usually a sandwich or canned meat, and plenty of water. He wears knee boots.

Reelfoot Lake, a few miles across the state line from the Bend, draws fishers from throughout the southeast. Its shallow but vast water is home to catfish, crappie, and large-mouth bass. Lake fishing has long been a way of life here.

Roy, who is seventy, prefers to fish the Mississippi. It yields fresher, tastier fish, he says, and offers him peace and solitude. He taught himself to cast at nine. Watching him cast a ten-foot pole is like seeing a trebuchet hurl a bowling ball. It’s a clean, vertical arc that fires the five-ounce weight a hundred yards into the distance.

Roy has lived his entire life on the Bend, save for a few weeks he spent in Tennessee. A neck injury, decades back, has limited the universe of jobs available to him, so he doubled down on what he loves most: fishing. Although he takes care of his mother and works odd jobs for the Bend’s absentee landowners, he spends most of his time on the water. He received positive reinforcement at an early age for helping to feed his large family, supplementing the garden work of his parents to produce a tableful of fresh food every night.

“It put a few meals on the table, and I guess it saved us a few dollars off and on, here and there, rather than going to the store, but mainly we raised a lot of garden,” he said. “We had a big family; there was ten or twelve of us here at one time.”

An autodidact, he learned how to read the water. He can gauge its speed from shore. He knows how weather in July will affect spawning in March. He plans ahead: If he is fishing on one of the Bend’s small lakes, he will take a chainsaw with him, cut off dead limbs, and stick them out in the deep water to attract summertime fish.

“If I lived somewhere else, I’d have a different lifestyle a bit, I’m sure,” he says, a can of Dr Pepper bulging from the breast pocket of his flannel shirt. “It’s just where we are, what family you’re raised up in and where you are. I told Mom, if we were raised up in Louisiana, I’d be up hunting alligators sometime in the past.”

February is peak season, the cooler water temperatures giving the meat a cleaner taste. In the morning Roy packs a sack with a sandwich, cinnamon rolls, and water. He waits until noon to launch, as the sun is beginning to heat the water enough for the fish to become active.

Using two anchors, one off the bow and one off the stern, he settles down in the current and casts. As the fish come in, he keeps his haul in a livewell or a stringer off the side of the boat. On a good day he will haul in about fifty catfish, a better day closer to a hundred. Sometimes he fishes buffalo using his bow.

He cleans the catch in the backyard and then gives away most of the fish or seals them in Ziploc bags with water to freeze. He leads me into the kitchen to a waist-high reach-in freezer that sits beneath portraits of the Wilson family and of Ronald Reagan. By itself on a shelf next to the pictures is a Ronald Reagan action doll. The Wilson house is small. It’s heated by a stove positioned just inside the front door. In the living room, Miss Daisy watches television. Roy pulls out three tightly packed Ziplocs of frozen blue catfish. He loads them into a foam cooler, covers them in ice, and hands them to me.

He gives fish to friends, to siblings, and to the Lynns and Whitsons. Sharing his work, his craft, is an act of joy, nearly as much so as the catch itself.

“It is rewarding,” he tells me. “You don’t think about it until you get later on, years past, but you say, ‘You know, they ate a few meals off my labor.’ That’s kind of rewarding.”

It was a meal of substance, if not refinement. Free of pretense but full of flavor.

After leaving the Wilsons’ I head deeper into the Bend to visit the youngest, and northernmost, Bend family: the Lynns. Seeing my cooler full of fish, Donald Lynn says Roy’s catfish is the tastiest he’s ever eaten.

“You can take that fish, drop it in the deep fryer, the oil, and you can use that oil the next day to fry chicken,” he says, examining my cooler after I pull into his driveway. “It don’t taste fishy. A lot of catfish tastes muddy, especially on the Mississippi where he’s catching ’em.”

Donald, a third-generation Bend resident, lives with his wife, Kristi, and daughter, Adrianna, at the end of Stepp Road amidst a constellation of modern barns, sheds, and houses once occupied by Stepp employees. Alfred Stepp was seen by many as an influencer of the Bend, organizing residents as a voting bloc and using his connections to give the Bend a county-wide voice. The Stepps raised cattle, and Alfred shooed away any aimless visitors and sightseers who disrupted his herd of twenty-five hundred. Donald Lynn’s grandfather first came to the Bend to work for Alfred. Donald’s parents also worked for him and, after Alfred passed, for the widowed Adrienne Stepp. When Adrienne died in 2002, the Lynns were rewarded for their years of loyalty to the tune of 2,267 acres, making them the largest landowners on the Bend. The large bell in the Lynns’ front yard was used by a resident cook to summon Stepp employees in from the fields for meals. The former Stepp residence sits farther back on the property, empty, modest, and sagging with age.

The Lynns don’t get many visitors. Most folks pull off at the state line or turn around at the cemetery. Security cameras are positioned throughout the property, and from the couch in their living room I watch the family’s two yellow labs sniff my truck on the security monitor. On the walls above us are the mounted heads of a half-dozen trophy bucks. In the corner of the room are enough guns to adequately arm all three of them: Donald, Kristi, and Adrianna.

After coaching me on how to prepare the fish, Donald leads me outside to his four-wheeler and we speed off into the heart of his property to his own fishing spot. Yelling over the motor and whipping wind, he tells me about the 2011 flood, which submerged the Stepp house up to the top of the chimney but came just short of the Lynns’ house, which is built on a gentle rise. During the flood, Kristi and Adrianna stayed in Tennessee with family, but Donald stayed home, taking his boat to and from high ground.

“Everything changes, you know that,” he says. “This ain’t really changed a whole lot, just fewer people. That’s the way that’s changed, and with the flooding problem and all that, you don’t really have to worry about nobody really building back.”

We pull up to the bank of the sixty-six-acre Watson Lake, where he and his siblings grew up fishing and where he taught Adrianna. He points into the distance and tells me about the incarcerated people who escaped from the Lake County Correctional Complex in the 1980s and tried to cross the Mississippi on driftwood. They all drowned.

Then we whiz into a back field, his dogs running along beside us in the gray February afternoon. He slows to a halt but leaves the engine running. He points out an eagle’s nest to our right, and the smokestack of the aluminum plant in New Madrid, Missouri, across the river to the north. Sometimes, on Friday nights in autumn when the wind is just right, he is able to hear the pep band playing at the high school football games there. Donald attended school in Tennessee. He remembers his older brother David, not even a teenager, driving them from their house to the bus pickup at the state line, stopping to pick up all the other Bend children along the way. Donald played high school football at Lake County High, just south of the state line in Tiptonville. In 2019, when Adrianna was a student there, Lake County won a Tennessee state title. She was the only Kentucky kid in school.

When we return to the house, Kristi Lynn loads me up with more food. Two jars of pickled okra and a jar of tomato jelly, both homemade, and more pecans to go with Winston’s. A freezer full of meat—plus canned veggies, fruit jellies and jams—these have saved Donald’s family many car trips, he says. He ate these foods growing up and ate them when floods stranded him. They are foods of preservation.

I ask him if he envisions a time when the isolation wins, when nobody lives out here anymore.

“I kind of do,” he says after a brief pause. “We’ll probably be the last.”

I placed one of my catfish Ziplocs in a large metal dog bowl to thaw during the eight-hour drive home. Back in Asheville, I stopped at the supermarket for buttermilk and canola oil for frying, and I credit beginner’s luck for the beautiful, flaky orange catfish that I enjoyed for dinner that evening. I fanned the Lynns’ pickled okra a third of the way around a white plate and I mirrored it on the other side with Roy’s catfish. I filled in the remainder of the wheel with Winston’s pecans and plugged the middle with a hubcap of tomato jelly. It was a meal of substance, if not refinement. Free of pretense but full of flavor. Unbridled. I took a picture, then cleaned my plate.