If You Don't Like Millie Jackson...

Before there was a Yeehaw Agenda

By Charles L. Hughes

Photograph © Glasshouse Images/Alamy

Country music always felt like home to Millie Jackson. “Growing up in the country,” the Georgia-born r&b star told writer Jack Lloyd, “we didn’t have black radio, so I’ve always been a country-rocker at heart.” Even as she gained fame in the 1970s with frank, funky discussions of love and sex like “It Hurts So Good” and the Caught Up albums, Jackson made room for her earliest musical love. “I’ve included at least one country song on just about every album I’ve ever done,” she noted, even scoring a top five r&b hit with a smoldering take on Merle Haggard’s “If We’re Not Back In Love By Monday” in 1977. But, even after this success, one barrier remained solid. “I’ve wanted to do a country album for a long time,” she told a reporter in 1981, “but [the record company] never let me.”

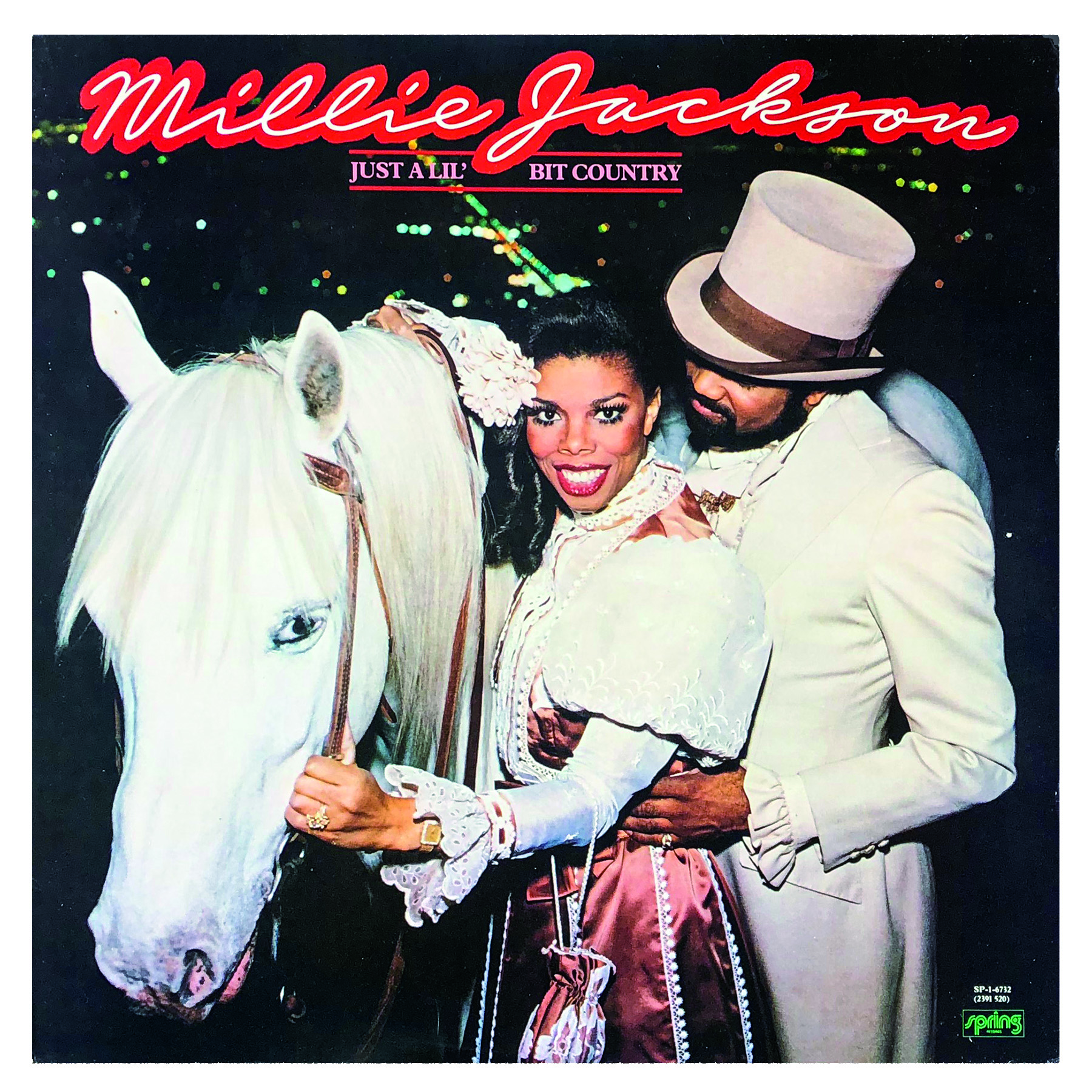

That changed later on that year, with the release of Jackson’s album Just a Lil’ Bit Country. Recorded in Nashville, the album features Jackson performing country hits in her trademark vocal style that interlaced breathy intimacy, sweeping power, and an easy familiarity that made each listener feel like they were in private conversation. She delivered these performances over arrangements that ranged from faithful interpretations to transformations driven by disco rhythms and rock guitars, supplied by a group of studio pros, including bassist Bob Wray and drummer James Stroud. This juxtaposition was signaled on the album cover. Eschewing rural or old-fashioned imagery, the image features a beaming Jackson in a frilly spangled gown accompanied by a white horse and tuxedoed male companion as city lights sparkle behind them. While not a commercial or critical success, and largely forgotten in subsequent decades, Just a Lil’ Bit Country is a compelling example of how Black country artists have historically remixed and reimagined a genre that too often ignores or overtly excludes them. It is also a great record.

Two crucial changes led to Jackson’s ability to release a country album. First, she renegotiated her record deal, which allowed her greater creative control. Second, country was then cresting the wave of the soul-and-disco-influenced Urban Cowboy boom. Just as earlier generations had adopted (and appropriated) blues, jazz, and r&b into their recordings, now the country charts pulsed with hits that incorporated the sounds and energies of the dance floor, from the Bellamy Brothers’ “Let Your Love Flow” to Dolly Parton’s transcendent “9 to 5.” Jackson—and her label, Spring Records—recognized an opportunity to bridge a seeming cultural divide. “The time seemed right for a country album now,” she said in 1981, “with the ‘Urban Cowboy’ thing and all of those black folks going around with cowboy hats and boots these days.” The album thus offered a disco-era reiteration of Black cowboy iconography that stretched back to the nineteenth century and has most recently been revived through the social media–driven rise of the “Yeehaw Agenda.” As in those other moments, Jackson’s remix intervened in a larger moment of discussion over the meanings of country culture and the specific role of Black people within it.

J ackson was hardly the first r&b artist to record country music. Most included country songs on their albums, and several stars—from Tina Turner to the Supremes—recorded entire albums of country material. The most important was Ray Charles’s groundbreaking 1965 smash Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music. As evidenced by the title, Charles paired wellknown country songs with lush pop and jazz arrangements: His mission was less to evoke the music’s past than to signal where it might go next. He succeeded. For the next nineteen years, up through Urban Cowboy, country artists and producers increasingly incorporated the sounds, songs, and even studio personnel behind r&b into their hitmaking formula. Contrary to its rootsy reputation, country had always been absorptive, bringing in successful pop styles to keep the music commercially relevant and commercially successful. Black pop had always been a favorite source, and country artists from Barbara Mandrell to Waylon Jennings incorporated the sounds of soul into their recordings, often backed by r&b-rooted producers like Billy Sherrill and musicians who started in Memphis or Muscle Shoals before making their way to the bright lights of Music City. R&b and soul kept country modern, pushing it to new levels of crossover success and cultural prominence in the 1970s. By 1981, Charles’s work seemed even more prophetic.

It makes sense, then, that Jackson opens the album with “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” the Don Gibson song that Charles made into Modern Sounds’ biggest hit. But Jackson was not interested in a throwback: As she said at the time, “I took these country songs and funked them up a little.” Indeed, Jackson turns the swooning ballad into a luxurious dance-floor jam. She even steps aside at one point for the band to dive into a polyrhythmic breakdown that would’ve been equally at home in a disco DJ’s mix, the breakbeats of early hip-hop, and the country dance clubs where “Urban Cowboy” country took flight. Adding the modern sounds to Modern Sounds, Jackson paradoxically sends the song in new directions and brings it all back home.

The album proceeds in this spirit, as Jackson both responds to individual country songs and remixes the larger assumptions of the country genre. Her stomping take on “Pick Me Up on Your Way Down” inverts the original’s bemused resignation into an assertive demand that recalls contemporaneous rock-influenced work by LaBelle or the Pointer Sisters, both of whom recorded country songs. Her take on Tammy Wynette’s hit “’Til I Get It Right” adds a horn section and insistent background vocals that reshape Wynette’s resignation into bluesy insistence. Jackson’s facility with country’s musical and lyrical tropes extends to her two original contributions, which fit seamlessly alongside the established genre standards. Jackson’s song “Loving You” maps shared terrain between pop, country, r&b, and adult contemporary, with Jackson’s lyrical invocation of “quiet storm” as the most direct linkage to the simmering sub-genre.

Even more impressive is “I Laughed a Lot.” On this original, Jackson offers a first-person narrative that charts the protagonist’s journey from cotton fields to Hollywood glitz. Such stories are common in country, usually serving to authenticate the singer as a true purveyor of the country spirit. For Black country artists, such songs take on additional meaning. The need to demonstrate musical and cultural bona fides has been critical to Black country artists, especially those whose original fame came in other genres and particularly in moments (like Jackson’s) when country’s racial borders have come under challenge. While not necessarily autobiographical, the song has a resonance with Jackson’s own journey from Georgia farm family to musical stardom that adds a layer of reality to her finely crafted storytelling.

Over a bubbling arrangement of picked guitar and punchy horns, Jackson’s protagonist recounts the experiences that brought her to where she is today. She acknowledges the “hard work” and “pain” of her rural youth while also fondly recalling her family’s strength and humor. Then, when she gets to Hollywood, she indulges in good drugs and bad love before emerging as an independent woman who can take care of herself with “her fans and her money” to help her. Contrary to tragic narratives of big-city alienation or romantic “old home place” nostalgia, Jackson cherishes all her experience as evidence of her strength and ingenuity. And unlike the fallen women or saintly mothers that populate country history, Jackson is on her own and having a good time too. She literally cackles at the end, reminding us that “Damn right! I’m having big fun!,” and then calling us to join her on the dancefloor: “Party disco, baby! Get it on the one!” Black statements of country authenticity simultaneously echo and subvert genre expectations; they reiterate well-known genre tropes while expanding understandings of what—and who—counts as country.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the last song on Just a Lil’ Bit Country. Jackson ends with a version of Kris Kristofferson’s “If You Don’t Like Hank Williams,” a boisterous ode to the outlaw country and Southern rock artists who emerged in the 1970s as a seeming counterpoint to the stifling music and politics of Nashville. Kristofferson shouts out artists like Willie Nelson and the Allman Brothers in his roll call, and at the center stands perhaps the most recognizable icon of rugged country realness: “If you don’t like Hank Williams,” Kristofferson gruffly assures, “you can kiss our ass.” Also recorded in 1980 by scion Hank Williams Jr., the song isn’t overtly exclusionary. But—like so many “real country” arguments, even in the supposedly liberated world of outlaw country—there are no Black frontmen included in the list of friends and heroes.

Jackson’s version flips the script. She turns the song not only into personal celebration—now it’s “Anybody That Don’t Like Millie Jackson” who gets the kiss-off—but also an all-Black all-star team, shouting out r&b and funk artists from Otis Redding to the O’Jays. But, unlike the disco-fied grooves or slow-burn soul of earlier tracks, Jackson sticks to the original arrangement, as steel guitar and fiddle drive a stomping honky-tonk two-step. “Y’all didn’t think we Black folks could sing no mess like this, did you?” she says at one point. “Well, y’all ain’t heard nothing yet!” Staking her claim and laughing at your foolishness, Millie Jackson is ready to confound any expectations. “I’m not saying that I’m the first,” she notes at the very end, and “I may not be the last.”

She certainly wasn’t the last. The album was not a hit, which Jackson chalked up to a lack of record company commitment to the project that included, in her recollection, being booked to perform at the Grand Ole Opry but pulled from the show beforehand. The white critics who covered the album largely dismissed it as a perhaps pleasurable novelty, although Billboard’s Nashville correspondent Kip Kirby said it “proves that experimentation doesn’t damage country music.” It quickly became a footnote in Jackson’s remarkable career. Jackson’s profound influence on subsequent generations of r&b and hip-hop performers has only come into greater focus: her proto-rapping, funky meditations on love and sex, and uncensored artistic persona serving as model for artists from Lil’ Kim to Erykah Badu. In a moment when the genius of Black women is the center of pop music both commercially and creatively, it’s easy to hear Millie Jackson in artists from Lizzo to Cardi B. But her country album—one that brought her back to her roots and that she fought to make—has largely slipped through the cracks.

Photo by Carter/Reddy

Still, four decades after its release, Just a Lil’ Bit Country has never sounded better. The performances and arrangements remain vibrant reminders of Jackson’s unique craft and the skill of the musicians with whom she worked. Her interpretations of country standards show the songs to be rich and durable, and her own compositions earn their place next to the more famous tracks. Its specific reaffirmation of country’s links to dance music and its sincere-but-not-too-serious approach have aged particularly well. The album is thoughtful, striking, and—perhaps most importantly—deeply pleasurable.

Just a Lil’ Bit Country has also never sounded more important. I hear it as a link in the long and ongoing history of how African American musicians have added new chapters in country’s development rather than simply serving as static influences from a semi-mythical past. It predicts the centrality of Black women to recent conversations about country’s racial politics, and I hear Jackson offering a precursor to the calls by artists from Mickey Guyton to Rhiannon Giddens and many more who have offered a historical corrective to marginalization and demanded greater recognition going forward. I hear Just a Lil’ Bit Country as a signal of how the best country music—whether mainstream, traditional/Americana, or whatever—always has one foot rooted in the past and one pointing toward the future. In its joyous irreverence and hybrid sound, I hear Lil Nas X, who performed similar trickster transformations in 2018 with cowboy fantasia “Old Town Road.” And I hear and see the mix of pop glamour and country realness that characterizes not only Lil Nas X, but also Megan Thee Stallion and Beyoncé, two key voices of the Black South whose artistry, frankness, and engagement with “country” as sound and identity suggest an additional kinship with Millie Jackson. (The visual similarity between Just a Lil’ Bit Country and Beyoncé’s Renaissance is only the most recent resonance.)

I also hear Just a Lil’ Bit Country as a powerful rejoinder to toxic narratives of country authenticity. The idea of a stable and discrete “real country music” is pure fiction, denying the stylistic blends and pop impulses that have motivated the genre’s musicians—Black, white, or otherwise—from the beginning. Moreover, this purist impulse fuels bigoted ideas, placing certain communities of people outside the circle and suggesting that they are interlopers at best and corrupting influences at worst. Moments of crossover—like “Urban Cowboy”—are demonized in coded language, while the accepted icons of country realness remain largely male, assumedly straight and cis, and almost entirely white. In this case, African American country artists are forced to repeatedly demonstrate their musical and cultural legitimacy to white gatekeepers who either implicitly or explicitly assume them to be outside of the traditions they helped originate and still re-create. And, as in everything, it’s even harder for Black country women.

In its stomping funk and aching ballads, in its heartfelt pleas and loud laughter, Millie Jackson’s Just a Lil’ Bit Country both convincingly debunks such nonsense and gleefully insists on a different conversation. The question isn’t whether Black people love country music. Black artists and audience members have shown that they do over and over again throughout country’s history. The real question is whether country music—and the country it claims to represent—will love them back. That question remains unanswered. But one thing’s for sure.

Anybody that don’t like Millie Jackson, you can kiss our ass.