The Singer

By Ashleigh Bryant Phillips

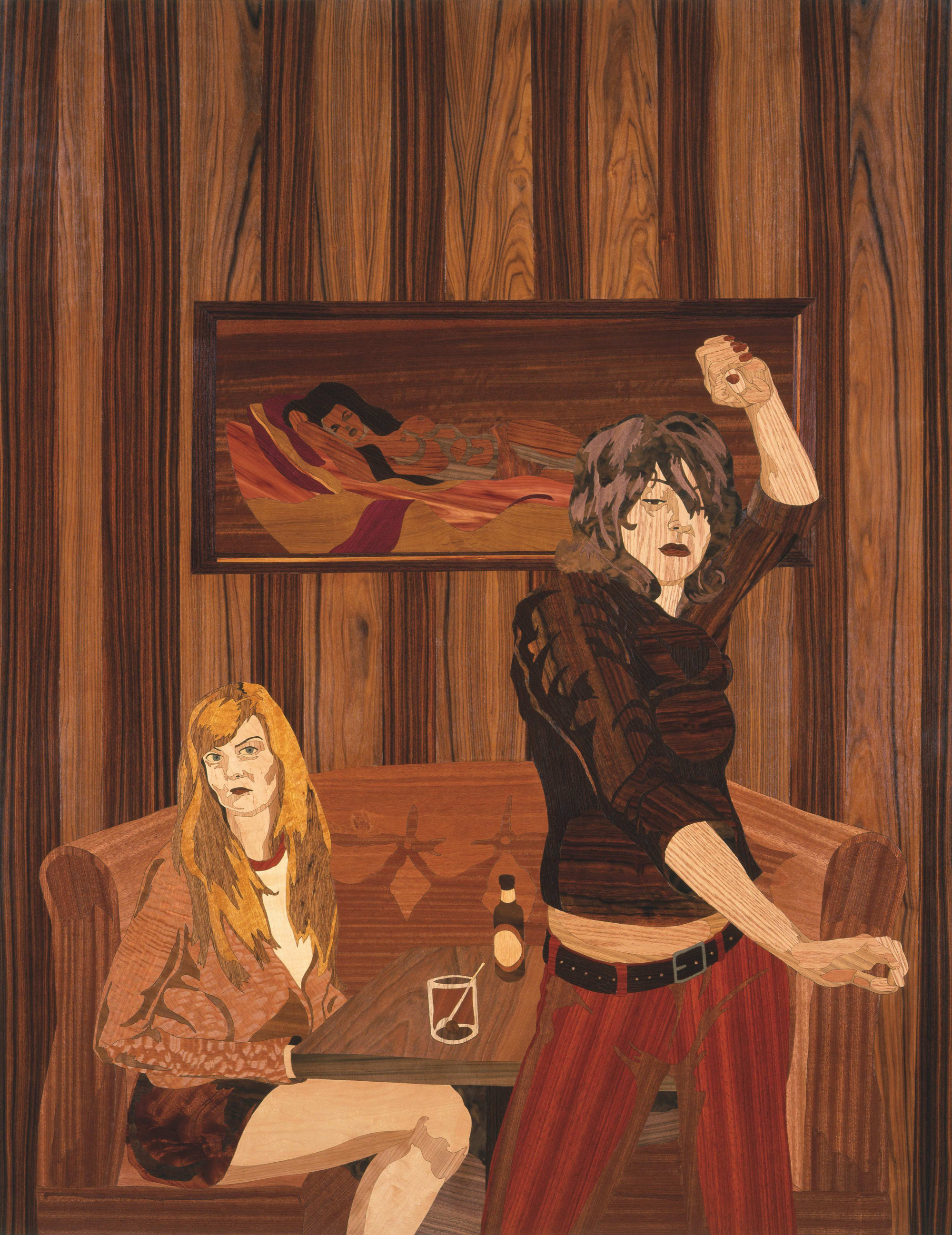

Jumbo’s, 2006, wood inlay and shellac, by Alison Elizabeth Taylor, whose work is on view through January 15, 2023, at the Des Moines Art Center. The accompanying monograph, The Sum of It, was published in October by Delmonico Books. © The artist. Courtesy James Cohan Gallery, New York City

"The center of our musical world...was Mother."—Bill C. Malone

I’m not sure where this story begins. I’ve been trying to figure out how to tell it my whole life. I don’t even know if this is the right way.

Let’s start here:

Imagine a woman. It’s winter, 1987. She’s driving home alone from choir practice. She’s the pianist. It’s night.

See her down there? The headlights shining a thin sliver. We need to see her from up here because I want you to see where she lives.

She lives in the middle of nowhere—where everyone before her has been raised. And it’s so dark at night here. But this woman has never known nights to be any different. Because this is the country.

So I want you to imagine that the woman is driving at night in the country of your mind. Think isolation, woods, barren fields in winter.

This woman, the pianist, we’re not going to hear her talk. As I said, she’s driving alone and she’s not the type to talk to herself. We’re going to hear her sing. She doesn’t have the best voice but there it is—a hymn that she learned in childhood. A hymn that always comes to her when she’s feeling lost or abandoned.

Imagine any hymn you know about being weary and wanting rest, perfect submission, perfect delight.

Now notice that there’s only one rooftop amidst the fields and woods. This is the home the pianist is heading toward. Where she prays over supper, and puts her feet up by the fire. Where she rocks in the rocking chair, and has an apple for dessert. Her children are grown and gone.

And see that light in the window? That’s the living room. Her husband is there waiting, smoking a cigarette, watching the news. He’ll get up and turn off the TV when she comes in, in case she wants to play music. She often does. For their thirtieth wedding anniversary she made a card for him. The front of the card was a flower that said, “My love for you just…” And then he opened the card, it opened downward, the stem of the flower unfurled all the way to the floor. At each fold the card read:

Grows

&

Grows

&

GROWS

MY LOVE FOR YOU JUST GROWS & GROWS & GROWS.

But let’s go back into the clouds and look down again. See that lone tree right off the road, right across from the house? Years and years ago when the farmers were making the fields, they decided to save that tree. It was so old and big. Majestic.

It’s been there ever since the pianist can remember. Suddenly, she veers toward it. Her headlights bend. Precisely and gently. Right into the tree.

Aunt Nell knows all the stories. How my grandmama ate peanut butter on her apples and wore gaudy jewelry as a little girl.

Aunt Nell’s really my great-aunt by marriage, but no one says that in the country. In this story, I’m calling her Aunt Nell.

We’re gonna move in time again. This time it’s 1947 and we’re at the foothills of some mountains. In the middle of the woods, down a worn path, there’s a dirt-floored shack. Hear that woman screaming? She’s giving birth to her third child. The baby’s early.

She’s born with a veil over her eyes. The mother has always heard about these kinds of births but never thought she’d have one. It means her baby girl is a seer. She’ll be able to see straight through to people’s hearts. When the doctor finally makes it out to the house, he’s surprised that the baby has survived through the night. The baby is my aunt Nell.

Her daddy is a sharecropper. He’s also in trouble with the law. He moves the family from state to state. Tells them never to use their real names.

Aunt Nell watches her mama give birth to nine more children. She’s curious about life. She loves to read, steals books from school. She gets to name her younger siblings after her favorite characters. They have two beds to share between all of them.

So at fifteen, Aunt Nell is working as a waitress. A young tall man comes in. And then he comes in again. He orders black coffee, puts molasses on his biscuit.

And then all of a sudden Nell’s daddy picks up and moves the whole family to another farm. This time over three hundred miles away.

Nell writes letters to the young, tall man. She’s unsure of her spelling, but she’s sure of her words. They are the truth. He writes her back. And then he drives all the way down to see her. He tells Nell to open the glovebox. She finds an engagement ring.

The young man is my Uncle Everett. He drives Nell all the way back to his home. They drive past the big old majestic tree and to the church his whole family was raised in. Everyone is there. Including his sister, my grandmama, the pianist. She plays the wedding with a little girl in her lap. The little girl is my mama. She has blond curls.

My aunt Nell begins her new life. She listens and writes the stories of her new home in a sacred place in her heart. She does anything anyone asks of her. She plays patty-cake with my mama. Later she helps Mama pick out my grandmama’s casket. And she’s the first one at the hospital, waiting to hold me after I’m born.

I never got the chance to know my grandmama, she died before I was born.

In one version of the story, my Uncle Everett refuses to go to her funeral. She was his big sister, she toted him on her hip. He gets a backhoe and takes down the tree.

In real life, the tree is still standing. And everybody knows what happened there. There’s no need to tell it.

I f you come back home with me, you’ll see that tree. We pass it every Sunday on the way to church. And my mama won’t look at it. She pretends it ain’t there.

Mama doesn’t really tell stories. She says she doesn’t remember.

But she told me this one when I was grown:

She’d just moved home after college. She was training for the volunteer EMS. They got a call about a wreck. When they got to the location, nobody wanted my mama to see it. Everybody knows everyone, everyone knows what it looks like. My grandmama was an angel, a pianist. Everyone loved her. She never hurt anyone to save her life.

In Mama’s version of the story, my grandmama died of a brain aneurysm. That’s why she drove into the tree. She was still wearing her winter gloves.

After her mama died, my mama got married, had children, went to work, and then when work was over, she’d lay in bed. She’d sleep. No one ever said the word depression.

But my mama has always had this gift. She can sing. And when she sings, she always harmonizes. It comes to her so naturally.

To create volumes, to create multitudes, to never be alone.

On Sundays she sang in the choir. Daddy would look down at me and say, “Y’all hear your mama?” It was always easy to find her voice.

I tried to pretend I saw my grandmama playing the piano for my mama to sing. But it was hard.

E veryone said my birth was a blessing. I was born thirty-some months after my grandmama’s death. My mama didn’t see a therapist until she was pregnant with me. She didn’t have pictures of her mama in the house.

My grandaddy turned his spare bedroom into a memorial for my grandmama, hung up photos that ranged her whole life. Got special light pink carpet put in. Framed the Valentine’s Day card she’d given him. My love for you just GROWS & GROWS & GROWS.

No one was allowed to sleep in that room.

Not until I came home from college to take care of Grandaddy when he was dying. I gave him his pills, tucked him in at night, and made sure he was there in the morning.

In the living room—the same living room we saw at the start of the story, when we were in the clouds at night, my grandaddy was waiting with the lights on, smoking a cigarette. But now he’s in bed. And I’m alone looking at my grandmama’s piano stool. I loved to spin the seat of it when I was little, like I was turning the helm of a great ship. But this time I sit on it, try to pick out a hymn on the piano. Have Thine own way Lord, Have Thine own way, Hold over my being absolute sway. I stay at the piano until I have the chorus. They say my grandmama had tiny hands. How did someone with such tiny hands master all these keys? And I see my grandmama playing. She’s moving quickly cause her fingers can’t reach long. And there’s my mama. She’s a little girl, standing at grandmama’s shoulder, watching, singing.

A little animal was crying out in the yard. The sun was starting to set. I found a black kitten stuck in Grandaddy’s wood pile. He was in rough shape. And I knew Grandaddy would throw a fit if he found out. But the kitten slept on my chest in the special pink carpet room for Grandmama.

When we went through Grandaddy’s things, we found a picture of my grandmama as a little girl. She was laying in the grass, snuggling an armful of squirming kittens.

T hey say I was really shy when I was little. I sucked my thumb longer than I should have, had this cotton doll named Willie that I took with me everywhere. Maybe instead of shy I was scared? I don’t know what I was afraid of.

Here’s a story from when I was about seven:

I walk right up to the preacher before church and tell him that I’d like to sing. All by myself, in front of the whole congregation.

I sing a hymn that was written centuries before I was born. One I’d never read, but knew from memory. I’d heard my mama sing it. There is a name I love to hear, I love to sing its worth, It sounds like music in my ear, The sweetest name on earth.

After this, everyone wanted me to sing all the time. I sang, alone, without accompaniment, in church, at ball games, at birthdays and funerals. Everyone was so proud of me. But it only lasted a couple of years. Wasn’t before long that I stopped.

In one version of the story, Aunt Nell asks me to sing a song at the church spaghetti supper. It’s from the point of view of a woman who is remembering something that happened when she was eight years old. Her daddy’s beating her mama, he always has. So the girl goes to the fair in town to get out of the way. When she comes back home, her mama has set the house on fire. And you never figure out if the mama survives or not. Let the weak be strong, Let the right be wrong.

In the other version, I’m not singing the song. We’re watching another woman in our church sing it. We’re all quiet. No one moves, no one makes a sound. Somehow a spotlight’s shining on her in the fellowship hall.

Then the spotlight moves out into the audience. Roll the stone away, Make the guilty pay.

And there’s Aunt Nell. She’s crying.

Whether or not I sing “Independence Day,” the fact is, it makes Aunt Nell cry.

And I don’t want to sing again.

Aunt Nell loves to tell this story:

My mama is still pregnant with me, and Aunt Nell is praying and praying that they’ll find someone to take care of me once Mama goes back to work.

One night, Aunt Nell sits up in her bed, and written right across from her, above the doorframe in shining golden letters it says: ANNIE RAY REYNOLDS.

When Aunt Nell tells the story, she holds her hands out in front of her and pulls them apart, like she’s letting the light in.

I magine a busy port town in 1949. People are always coming and going. There’s a movie theater on the corner. A young woman is on a first date in this movie theater. It’s a horror film. And someone is walking up and down the aisles dressed as the monster. Make it the monster that terrifies you the most.

Look at the young woman running out of the theater. Not with abandon but with composure like she’s an expert at holding pain. Her date runs after her and puts his hands all over her to comfort her. They get married, then divorced.

She never talks about her first husband again, becomes a nurse, cares for a man who says he’ll always listen to her. She sits by his bed, puts a wet washrag on his forehead, and tells him how scared she’s been her whole life.

One night when she was little, she called and called for her daddy and brother to come in for supper. They were out in the barn, getting the cows settled during a storm. But it was already lightning, raining sheets. She called and called for them. But they never came.

Her mama told her they’d been struck by the same bolt of lightning. They were in heaven now, looking down on them.

The young woman nurses the sick man back to health. He takes her hand in his. They get married and he moves her back to his home. Near the big old tree we started with, but across the little river.

They miscarry multiple times. She imagines the lost babies as angels in heaven with her brother. He’s bouncing them on his knees.

She thinks of this even after she has her only daughter, while she works in a factory, is active in her church. Until one day, she’s a widow and her daughter never comes home. She sits alone in her house and listens to music about walking the streets of gold.

She’s in the grocery store when another woman approaches her. It’s my aunt Nell. “You don’t know me,” Aunt Nell says. “But I know you, you’re Annie Ray Reynolds.” Then she leans in closer, “I saw your name in a dream.”

Miss Annie Ray kept me at her house sometimes. It was filled with angels. An angel flying in the window. An angel in prayer. An angel blowing a kiss, holding a butterfly, sleeping on a cloud. Angels laughing. Angels singing. I saw Miss Annie Ray’s brother, my grandmama too. Their mouths were perfect little Os.

There was also the music Miss Annie Ray always played. Because He lives, I can face tomorrow, Because He lives, All fear is gone; Because I know He holds the future, And life is worth the living, Just because He lives!

Her stories always came back to her brother. She said his name every day. She said it like it was the most beautiful word she knew.

Miss Annie Ray didn’t know my grandmama, but she said that her husband had been distant cousins to her down the line.

Everything feels connected. This is what I’m trying to tell you.

When she died, Miss Annie Ray’s obituary listed me as a survivor. “A very special young woman that she considers her own grandchild.”

She taught me how to wash behind my ears. She came every time to hear me sing. And even then, when I was a child, she said, “You should write these stories down someday.”

After I stopped singing, Miss Annie Ray gave me a diary for my birthday.

Or was it Aunt Nell?

I remember asking Aunt Nell if she ever had a diary. It went something like this:

Aunt Nell: Oh yes.

Me: (interrupting) Really? Where is it? Can I read it?

Aunt Nell: Oh, I don’t have it anymore.

Me: …

Aunt Nell: The day I married your uncle Everett, I burned it.

Me: But why?!

Aunt Nell: There was too many hurt memories. I couldn’t hold on to them anymore.

L ook now at a crowded kitchen, where everyone’s sitting at the kitchen table. It’ll sit six comfortably, eight can squeeze in. I always sit beside Aunt Nell. She always sits to the left of Uncle Everett. He’s always at the head of the table.

But he’s not at the table now. He’s in the living room in a hospice bed. He’s dying. He’s saying he’s seeing his sister in the walls. Look at him motioning his hands into the air. Aunt Nell says it’s the other side.

We go in to see Uncle Everett one at a time from the kitchen table, where we’re all waiting to say our goodbyes. This is the kitchen table where Aunt Nell showed me how to press leaves into books. Where she taught my mama how to can snaps. Where my grandmama painted her fingernails.

All of Aunt Nell’s siblings are here. The ones she named after her favorite characters: Nancy, Jo, Amy. They start talking about their sharecropping childhoods, slung across so many states. Telling so many stories together, all at the same time. Collecting chestnuts, feedbag dresses, keeping meat in a bucket at the bottom of a stream. Then…

“I won’t never forget the time we found Mama hung up in the shed by her wrists.”

“Daddy had slashed her cheek open.”

“Amy tried to run away.”

“Things were bad.”

“Daddy told us not to use our names.”

“He didn’t want anyone to know who we were.”

“One time Nell walked to town ’cause Mama needed flour.”

“And Daddy had just beat her, blood was coming through the back of her shirt.”

“The folks in the store wanted to know who she was, if she was alright.”

“And she told them her name. She told them what was happening.”

“That night men from town came out and found Daddy.”

“Drug him out in the front yard, beat him so bad.”

“I think they kicked out one of his teeth.”

“Mama stayed up all night tending to him.”

“I was glad to see him hurting.”

“But then he whupped us all again once he got the strength.”

“I won’t never forget how he looked at Nell then. Y’all remember?”

“Like the devil.”

Hear Aunt Nell coming down the hall? She’s coming to the kitchen. Her sisters stop the stories. But Aunt Nell heard them anyways. She leans against the kitchen table and says, “Why are y’all dragging up those bad memories?”

When I think of my earliest memories, it’s Aunt Nell in front of me, feeding me with a spoon. It’s Aunt Nell, rubbing my back so I can get to sleep. It’s Aunt Nell sitting me down at the kitchen table for homework, helping me stay in between the lines.

After I stopped singing, Aunt Nell told me that God had given me a gift and if I stopped using it, He’d take it away.

I want to believe I still have a beautiful voice.

I know my mama thinks so—

Although I never have been, and never will be able to harmonize like her—no matter how much I listen to her sing.

Aunt Nell never talked about when she was little. Only told me she never had a birthday until she came into our family. Imagine celebrating your first birthday when you’re sixteen.

And I don’t know if Aunt Nell really burned her diary.

But I know that she’s never going to let me read it.

And I’m not sorry for telling you these hurts. I want you to feel them.

I wanna make Aunt Nell proud, Mama, and Miss Annie Ray too.

I still wanna be a singer, use my gift somehow.

Like I said, I don’t know if this is the right way.

According to Aunt Nell, shortly before my grandmama died, she stood in the same kitchen that I’ve told you about before and said, “I just want some peace.”

She prayed for peace.

Peace for what?

I don't know where the story ends either.

I told Mama I was working on this new story.

She wanted to know what it was about.

I told her singing. I told the editors singing, storytelling, and survival.

But really, this is something I wanna show my mama and Aunt Nell. They’re the only ones left that can read it.

I love you.

I’m sorry.

I’m so proud to be yours.

I keep the family hymnbook on my nightstand.

The Grows & Grows & GROWS card is framed above my bed.

While I was writing this, a friend came over. She sat on my grandmama’s piano stool.

And I started telling the story again.

My grandmama was 5'2". Ate apples by the fireplace. Let the kittens crawl all over her. Chew her hair, lick her fingertips. She went to school with scratches on her little wrists. She was a pianist.

I 'm back home. I’m walking with Aunt Nell. She stops and points to the clouds above the side yard. “Remember when I’d bring you out here and put you on a blanket to look up at the clouds?”

She said, “You loved looking at ’em, we'd stay out here all afternoon.”

I don't remember.

“We’d lay down and make stories up from what we saw… Those were the first stories you wrote,” she says. “Don’t you remember you took one and gave it to Miss Jenny?”

Miss Jenny was my sixth-grade teacher.

“To this day, every time I see Miss Jenny, she’ll tell me how much she enjoyed that cloud story.”

“I wonder what it was about,” I say.

“Oh, I don’t know… You’ve always had an imagination.”

Then I follow her up the porch steps and into the house.