Will the Real Mr. Heartache Please Stand Up and Cry?

The surreal tragicomic legacy of Johnny Paycheck and David Berman

By Rebecca Bengal

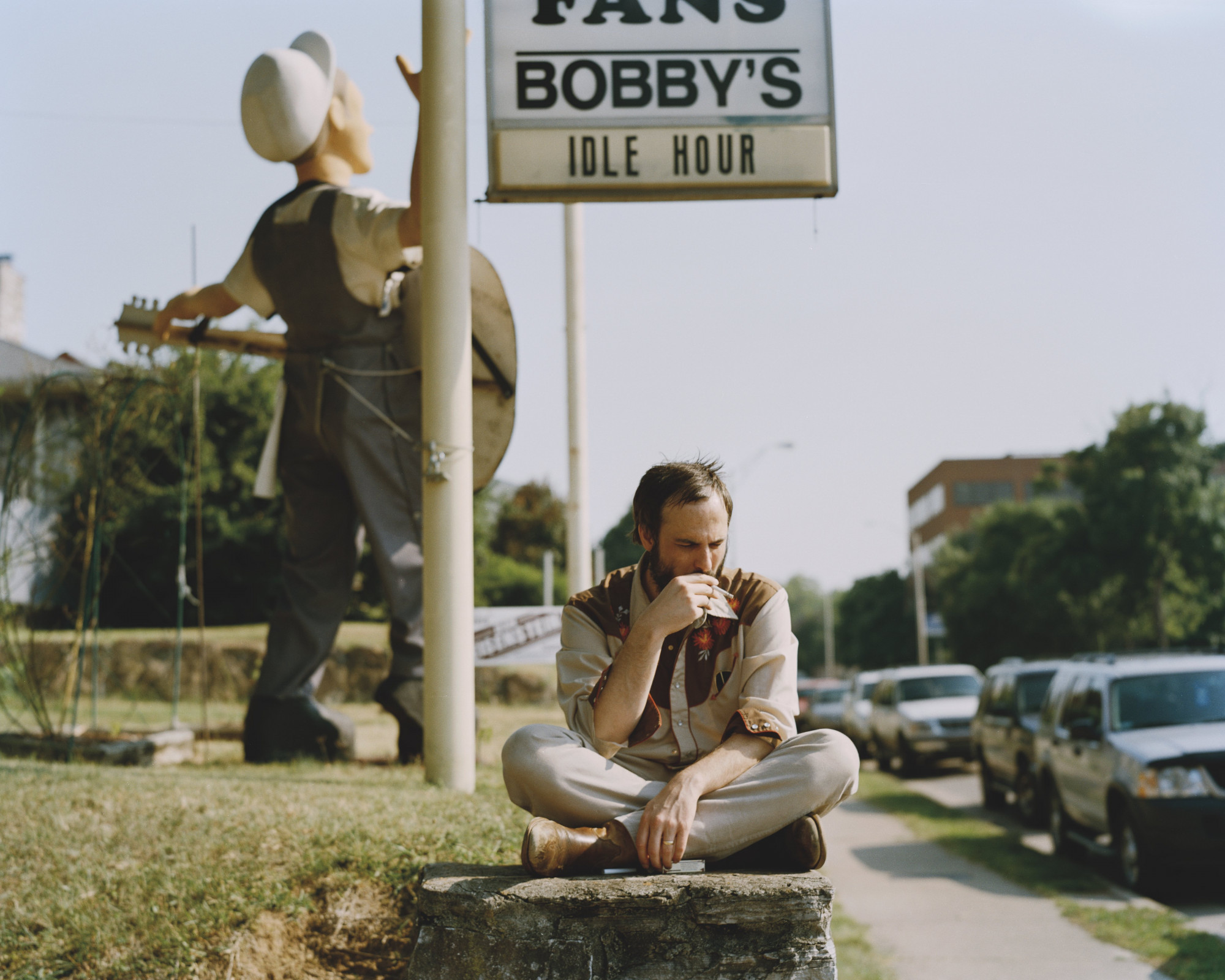

Photo © Bobbi Fabian

Inside the metal trash can are two things: a white angel sculpture and a McDonald’s cup. Ceramic and Styrofoam. I’m standing in the wake of the graveyard lawnmower, which is now prowling somewhere on the far side of the grounds. Fresh cuttings stick to my boots as I loop around the studded, sloping hills of Woodlawn Memorial Park, scanning names for the country and famous. Two headstones sing to each other…My Blue-Eyed King. My Green-Eyed Queen… he died six years before she did. Maybe they’d written their engravings together, picked out their plots, and gone out somewhere nice to lunch.

It’s October 2020 and I’m in the early stages of a drive from North Carolina to Tucson. In western Tennessee, even the I-40 rest stops are musical. Fill up your water bottle near a portrait of Tina Turner, walk your dog on the—of course—Rufus Thomas trail. On the side of a Nashville freeway, my hotel room is decorated with a photograph of John Prine and another of the Mandrell sisters putting on makeup backstage. Cemeteries, the side trip of the pre-vaccine days of the pandemic—dead people don’t mind a visit, which is how come I end up having coffee among the burial plots and ashes of Tammy Wynette, Marty Robbins, Little Jimmy Dickens, Webb Pierce, Lynn Anderson, Red Sovine, Porter Wagoner, and too many other country singers to name.

Within the heart of the place is a fancy, fenced enclosure and an invitation: STEP RIGHT ON IN!, dominated by a massive arch inscribed POSSUM and a montage of renderings of George Jones. The grave of Johnny Paycheck rests somewhere a little south of Jones’s bootheels. My grandma would’ve approved of the matching, seasonally appropriate artificial flowers—in jarringly bright shades of orange, red, yellow. I approve of how Jones paid for Paycheck’s plot when his longtime friend and onetime bass player died, allegedly broke, at sixty-four. I especially approve of how he had him buried by the spot he’d marked for his own, as if to also ensure a lasting place in country music for Paycheck, underappreciated and misunderstood, and often whittled down by shoddy collective memory to the legacy of a single hit. The outsize popularity of Paycheck’s rendition of David Allan Coe’s “Take This Job and Shove It” is equivalent to that of his good friend Merle Haggard’s “Okie from Muskogee,” blighting out Paycheck’s remarkably varied catalog that swung from Orbison-like amplified psychedelic loneliness to the late Seventies radio-gold polish of “Slide Off of Your Satin Sheets.”

Jones and Little Jimmy Dickens were among the two-hundred-some attendees at Paycheck’s memorial, where there was also a sizable contingent of Hells Angels, who were as loyal pals of the notoriously hard-living singer as Haggard. “By and large, it was the roughest-looking funeral crowd I have ever seen,” the “Nashville Skyline” columnist wrote in the CMT. At the end of it, when Paycheck’s own favorite of his songs was performed, perhaps the most personal, they all stood in an ovation. “The Old Violin” is a ballad of rock-bottom despair: “I feel like I could lay down, and get up no more / It’s the damndest feelin’, I never felt it before.” Like the best of Paycheck’s songs, it warps utter hokiness into unvarnished feeling. When Paycheck leans on the trope of staring into a mirror, seeing in it a mirage of the instrument, what flashes into the mind is the cover of Armed and Crazy, Paycheck looking a little stunned and preening, hands awkwardly attempting to tuck into tight, too-small vest pockets, face half swallowed by one of the gigantic hats he’d wear to offset his 5'5" frame. It’s hard to shake the memory of that wild-eyed gaze as he cranes into a vocal register of lonesome yearning. But where Hank might have yodeled, Paycheck carries the melody to a place that feels at once too much, too obvious, and yet totally startling and stunning in its plainspoken admission. “And just like that, it hit me / Why, that old violin and I were just alike / We’d give our all to music / And soon, we’ll give our life.”

At Paycheck’s grave I had David Berman on my mind too. I’d come to reappreciate “The Old Violin” via the musician and poet, who posted a number of Paycheck songs at the beginning of 2019 on his blog mentholmountains, a sporadic collection that drifted freely between a post titled “Cowboy Overflow of the Heart,” readings from Robert Walser, and, in the months before Berman took his own life, paragraphs from numerous books by Thomas Bernhard. In July 2019, Berman released Purple Mountains, his first album since disbanding the Silver Jews in 2009, the group he’d started twenty years earlier with Stephen Malkmus and Bob Nastanovich of Pavement. The group released a half-dozen albums. Their enigmatic lo-fi sound became increasingly country as time went on, at a time when country wasn’t cool in indie rock, unless maybe it harkened back to Gram Parsons. On Bright Flight, the Joos covered George Strait’s unabashedly forthright early Eighties honky-tonk hit “Friday Night Fever,” slowing the tempo to a swaying drawl laced with pedal steel. Up there with the duets of George and Tammy are vocals by Berman and his wife, Cassie, especially on “Tennessee” and, on the Silver Jews’ final album, Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea, “Suffering Jukebox” and “We Could Be Looking for the Same Thing.”

Side two of Purple Mountains begins and ends with two perfect country songs: “She’s Making Friends, I’m Turning Stranger” and “Maybe I’m the Only One for Me,” both swimming in the milieu of Johnny Paycheck and maybe also Gary Stewart. Both bring levity to the album’s other songs of grief and solitude: “I Loved Being My Mother’s Son” and “Snow Is Falling in Manhattan.” But it’s side one’s “Margaritas at the Mall” with its end-times call-and-response, that hammers in my image of Berman as an inheritor to Paycheck, perhaps unlikely to some, but whom he’d name-checked in poems and cited in interviews for years. How long can this world go on, under such a subtle god? Berman sings, as if standing in the middle of the shuttered Applebee’s and Sbarro, a minimum-wage worker sweeping up around the last-call drinkers.

In some of the first press leading up to the release of Purple Mountains, with the writer John Lingan, Berman brought up Paycheck again: “He wasn’t much of a writer. He’s a dumb fuck, as anti-intellectual as it gets. There’s not much to like about him as a person. But there’s ten or fifteen songs of his that I put above all other music. I relate to him as an outsider. His voice is so moving. The tear in his voice.”

Ten years earlier, in a 2009 interview in the zine Minus Times, Berman regretted being too hungover to make it to Paycheck’s public funeral: “That evening at the Western Room a friend told me he’d gone. I was struck by my inability to ever do the right thing.” It was as honest an admission as any surrounding Paycheck, whose propensity toward liquor, drugs, and breaking the law was legendary even in proportion to the sizable constitutions of his hard-living friends. In Mike Judge Presents: Tales from the Tour Bus, Swamp Dogg (who composed the soapy Seventies crooner “She’s All I Got,” a big hit for Paycheck) and members of Paycheck’s backing band recount the time he illegally “test drove” so many vehicles after hours at a car lot that he stole the whole board with every key on the lot and dumped it in a creek. Once when he was backing Patsy Cline, he decided to take off in her car. Locked inside the gates of the fair where they were playing, he drove it around and around the perimeter until it ran out of gas. Before Paycheck got sober, his musicians reckoned, he’d go for a four-year stretch before he was apt to find a way to upend his entire life all over again. At a televised celebration for Paycheck in his sober years, Haggard took a seat on a sofa next to his friend, jokingly searched for a story about him clean enough to tell on air, and eventually came up with one dating back to “when they still put cocaine in Coca-Cola,” turning to the studio audience with an exaggerated wink.

At various times, Berman and Paycheck each landed in Nashville, where Berman survived an overdose in 2003, but otherwise came from vastly different places. Paycheck, born Donald Eugene (“Donny”) Lytle in Greenfield, Ohio, was playing talent shows by age nine and hopping freights across the country by fifteen; he’d eventually earn his GED in one of his many stints in jail, the last time after his gunshot grazed the head of a man who’d offered to cook him turtle soup. “What do you think I am, a country hick?” Paycheck allegedly said before he fired a shot. He’d changed his name legally to Johnny Paycheck in the mid-Sixties, adopting the name of a heavyweight boxer, and started spelling it PayCheck in his later years. Berman, the UVA grad who’d grown up between divorced parents in D.C. and Virginia and Texas, guarded art for a living in New York and wrote poems that strike a chord with the work of his mentors James Tate and Charles Wright, collected in his 1999 collection of poems, Actual Air. He would work his Jewish heritage into his band’s name, and when he eventually broke up the Silver Jews, he denounced his father, the corporate lobbyist Richard Berman who was nicknamed Dr. Evil on 60 Minutes for his aggressive tactics in favor of big tobacco and alcohol and against labor unions. In 1978, Paycheck showed up at a United Mine Workers rally where he performed his most famous hit, a jolt to the resistance.

Vocally they were opposites. Berman’s deadpan baritone underscored the tilted humor and searching wisdom of his own lyrics, whereas Paycheck’s craned upward into the altitudes. As his New York Times obituary put it: “Mr. Paycheck’s voice was high, searing and unusual: he bent vowels into a curious mixture of mid-South and Cockney, resulting in locutions like noit-spawt for nightspot.” Some of Berman’s own favorite Paycheck songs feel like they could take a page inside his Silver Jews lyrics, or inside Actual Air, in the way they assuage the most cosmic, bizarre, and mundane aspects of the universe and attempt to reckon with them all on an equal emotional register. But the material world is forever at awkward odds with the spiritual, and their failure to converge produces the comic gap between the banal and the sublime. In Berman’s poem “Governors on Sominex,” a boy kicks ice buckets behind a Marriott, the moon “hung solid over the boarded-up Hobby Shop,” and “Tammy called her caseworker from a closed gas station / to relay ideas unaligned with the world we loved.” In Paycheck’s mid-Seventies recording of “The Feminine Touch,” he inhabits a character who watches the significant products of his love slip away:

And I cancelled our subscription to the Ladies Home Journal

And told Avon not to call anymore…

The clock by our bed just gave up and stopped ticking

And the flowers on the mantel have died

The dust is gettin’ deep on everything but the ceiling

And I’ve lost all my homeowner’s pride.

Country songwriting has long leaned on exaggerated metaphors, the tropes of the down and out, underdogs and the tear in the beer, but often with a veil of irony. Lift that and you have a song like the Silver Jews’ “Honk If You’re Lonely,” from American Water, which lends a jagged, lovely, bittersweet melody to a bumper sticker platitude. If you can picture a door that swings open between love and bleak loneliness, between the existential and the comic, between the mystic and the familiar, Paycheck and Berman worked its hinges.

In the early Sixties, Paycheck released records on his own label, Little Darlin’, wandering to its far-out margins with personal, deeply felt, and just plain strange and surreal songs. They yearn for deliverance (Paycheck escaped from prison twice; the singer of “Ballad of Frisco Bay” is ready to die trying to swim from Alcatraz) and romance (the plaintive “Apartment No. 9” which would become Tammy Wynette’s first single) and ironically reckon with their rotten luck in love [“He’s in a Hurry (to Get Home to My Wife)” feels like a predecessor of Berman’s resigned character in “She’s Making Friends, I’m Turning Stranger”].

Ever heard an abject country song about nuclear holocaust? The narrator of “The Cave” picks his way through a desolate landscape, witnesses a “ball of tiny light,” and is left, at last, staring at the “shambles of a town / Where people used to live before the bomb came down.” In the dark and weird Little Darlin’ corners of Paycheck’s catalog, “The Cave” sits alongside songs like “(It’s a Mighty Thin Line) Between Love and Hate” and “(Pardon Me) I’ve Got Someone to Kill.” “Now that’s the Blue Velvet shit,” says my friend Cecile Duncan, host of the now dormant country radio show Downhill Swing.

They are also among his most forlorn. When Paycheck sings, “Will the real Mr. Heartache please stand up and cry?” he extends his voice pleadingly, piercingly, just to the point of cracking. In retrospect, his first hit, with Hank Cochran’s “A-11,” or his “Jukebox Charlie” (“I wanna play that jukebox and hear that song / Tells me how I feel since Baby’s gone”) might seem to be materially kindred to the Silver Jews’ “Suffering Jukebox.” But like Paycheck’s old violin in the mirror, staring down its inanimate loneliness, the jukebox stuck “in a happy town” is a nihilist avatar for the singer. It’s an anthem for the workingman artist, echoed by the swooning harmonies of its chorus: “Such a sad machine / You’re all filled up with what other people mean.”