Ja’Tovia Gary’s Cosmic Return

By Amarie Gipson

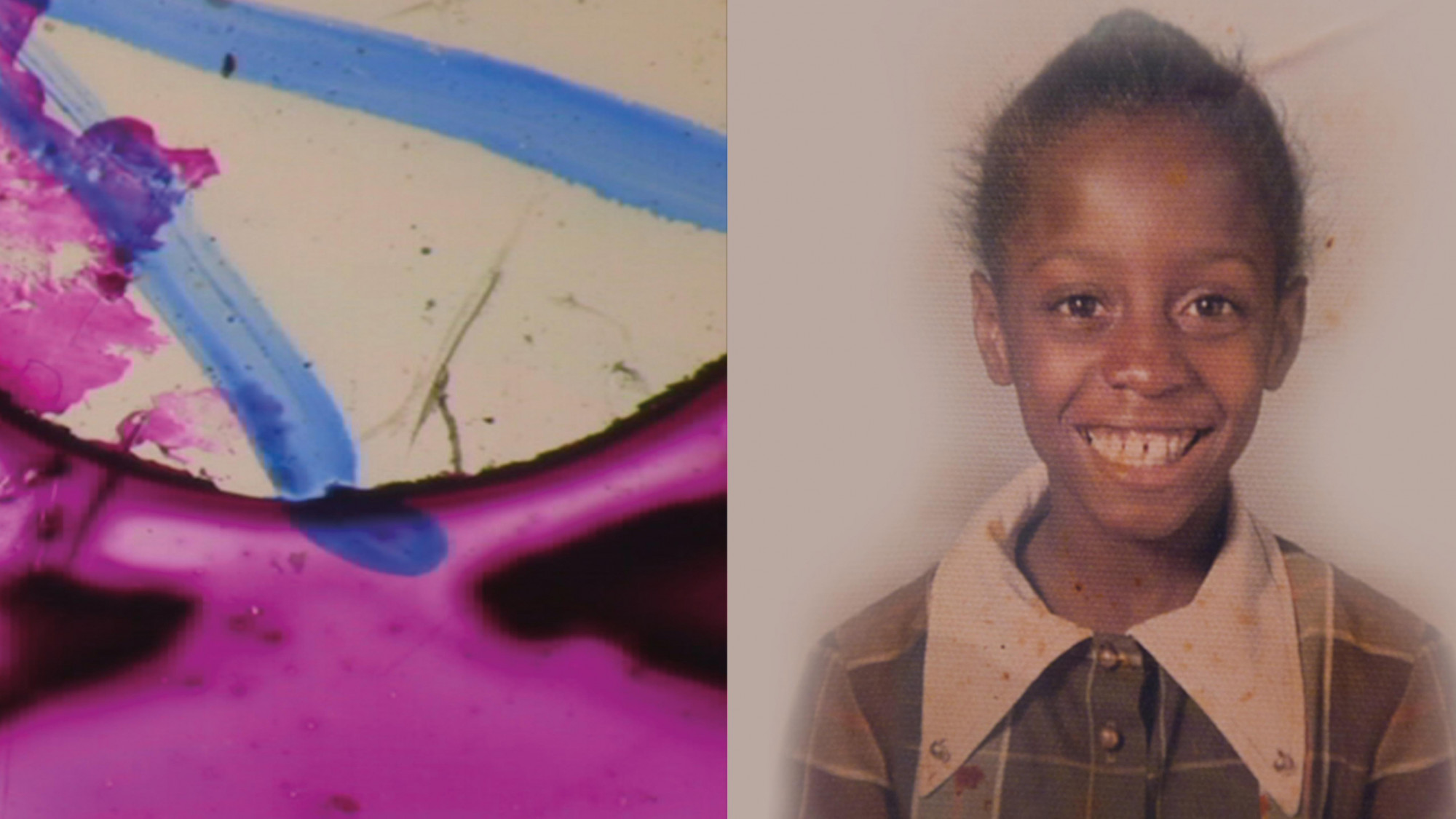

A detail from Precious Memories, 2020, an installation by Ja’Tovia Gary. HD and SD video from 16mm film on 3 CRT monitors, acrylic, dried cotton, moss, dried Helichrysum monitors © The artist. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert

A soulful chorus echoes through a mid-sized gallery in the Dallas Museum of Art. The voice of the late Aretha Franklin in her 1972 song “Mary, Don’t You Weep” cascades onto a room of viewers gazing upon two video screens. Black-and-white scenes of a baptism are collaged with old family photographs and home videos. In the center of the exhibition’s orbit, a larger-than-life-sized steel armillary sphere rotates with footage projection-mapped onto its cotton-covered form. In her aptly titled solo exhibition at the DMA, I KNOW IT WAS THE BLOOD, Texas-born interdisciplinary artist and filmmaker Ja’Tovia Gary pays homage to her Southern roots.

The show, displayed for a six-month run through November 5, marks a milestone moment in her career. It was conceived upon Gary’s return to Texas after sixteen years in Brooklyn, New York, through conversations with initiating curator Vivian Crockett, who recognized Gary’s well-deserved acclaim and wanted her homecoming to be realized at the DMA. It’s the sixty-fourth iteration of the museum’s “Concentrations” series, a project-based program that supports a solo presentation of new work.

Gary grew up right around the corner from the museum. She attended Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts. Several years after pursuing her passion for theatre and acting, Gary built her background in documentary filmmaking and Africana studies. She completed an MFA in 2014 and has spoken widely about her need to challenge the film world through both subject and technique.

Gary has racked up a string of fellowships and residencies, including the Guggenheim Fellowship (2022), Creative Capital (2019), Radcliffe Institute (2018), and the Terra Foundation for American Art (2016), where she spent a summer in France making her most well-known experimental short film to date, The Giverny Document (2019). Support for her practice oscillates, as she herself does, between the realms of film and fine art. She’s swept awards at national and international film festivals from Locarno to BlackStar, graced museum collections, and participated in countless group exhibitions worldwide. She’s also a founding member of the New Negress Film Society, a collective of Black women and nonbinary filmmakers defying the bounds of filmmaking through centering and protecting radical Black women’s voices. Earlier this year, New York City’s Paula Cooper Gallery mounted Gary’s second solo exhibition, You Smell Like Outside… With memories of skipping school to see exhibitions at the DMA with her friends and a mission to make the world safer for Black femmes, Gary has come home. The gravity of her return to the institution and to the city is immense.

During a Zoom interview from her home studio in Dallas, Gary and I discussed her work and the impact of mounting new work in her hometown. The Texas sun poured in from the loft windows as she began by detailing the events of the evening before our call: Her mother, dressed to the nines and eager to share Gary’s brilliance, had facilitated a second opening night of the show at the DMA that included several walk-throughs with family.

Photo of Ja’Tovia Gary by Ciara Elle Bryant © Ja’Tovia Gary. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

The exhibition’s central work, titled In my mother’s house there are many, many…, fuses the armillary sphere’s ancient structure with images of Gary’s aunts, grandmother, and cousins to amplify the way those Black women have been a cosmic and guiding force in her life. The use of cotton, a recurring material in her work, calls forth the history of brutality embedded in the cash crop while reclaiming its spiritual function as a tool for healing and restoration. On both sides of the sphere are screens playing Mitochondrial Montage, an eleven-minute prelude to Gary’s highly anticipated feature-length memoir film The Evidence of Things Not Seen. She describes the upcoming feature as “a critical look at the violence that permeates interpersonal relationships in families, transgenerational violence, [and] the things that have been passed down to us.” In the video, a young Gary is seen donning both blushing grins and discerning side-eyes while flickers of her signature biomorphic direct animations, created by her meditative etchings onto the film’s surface, appear throughout. A break in the music transitions into the voice of an older Black woman’s testimony of the beauty and empathy she found in filming her road trip through America. “Words are good, you know. You can tell somebody something, but it’s better when they can see it,” says Mary Lee Dunn, aka Aunt Mae, Gary’s great-aunt and collaborator.

Aunt Mae, now in her late eighties, is what Gary describes as an “industrious, diligent, hardworking, and determined woman” who inspired Gary to have “the gumption and audacity to decide we are worthy of being gazed upon just as white folks are.” She was born in Arkansas and worked on and off as a domestic before becoming a well-to-do businesswoman. Since the death of Gary’s grandmother when Gary’s mother was only twelve years old, Aunt Mae has been a matrilineal compass for the family. “She’s looking at me and seeing her sister,” the artist says. During one of many conversations about her life, Aunt Mae gifted Gary with six reels of Super 8mm film from her travels, the invaluable sum of which has both elevated and anchored Gary’s most recent work. Although they are generations apart, there’s a cosmic link between Aunt Mae and Gary’s shared affinity for documentation and the autoethnographic, an affirmation that her artistic practice has been in the making for almost a century. The video ends with a low-fi YouTube performance of “Because Of The Blood” by gospel choir Ricky Dillard & New G. The voices wash us clean. From Franklin to Aunt Mae to Dillard, the soundtrack that moves the video is a nod to Gary’s Pentecostal upbringing and the rich tradition of theatrics and performance in the Black Church.

Pushing beyond the conventions of her training in filmmaking, Gary has deepened her interrogations of power through sculpture and, most recently, performance. (She often appears in her films and has been quietly working with her high school theatre teacher to review her old monologues, using performance as a mode of self-actualization.) The exhibition welcomes visitors into Gary’s inner world with Precious Memories, 2020, a sculptural installation that reimagines her childhood living room. Amongst more minor elements like a framed photograph of her mother and theatrical lights cast onto a plush rug, a La-Z-Boy recliner sits in front of a three-monitor tower, each screen showing a different video: a remixed version of Louis Armstrong’s performance of “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South”; footage of her stepfather’s funeral, and a heavily pixelated adult film, so abstracted that it’s nearly unrecognizable. Here, Gary creates a surrealist, domestic environment that makes us aware of the way trauma manifests within and around us.

Stills from The Evidence of Things Not Seen, 2016-present, by Ja’Tovia Gary © The artist. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

On an adjacent wall is Citational Ethics (Saidiya Hartman, 2017), 2020, the installation’s companion piece and one of Gary’s first neon sculptures. A quote that reads, “CARE IS THE ANTIDOTE TO VIOLENCE,” is illuminated in purple neon tubes beneath brownish-red hands, reminiscent of a church or beauty shop sign with the slight shape of a headstone. Starting with Hartman, the series has expanded to include words from Gary’s beloved Toni Morrison and Zora Neale Hurston.

The Morrison citation went viral online and caused a stir among critics and viewers. Fashioned as a replica of the sign outside the infamous Lorraine Motel in Memphis, the site of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, the sculpture spotlights a line from Morrison’s 1987 novel Beloved that reads, “There is no bad luck in the world but white folks.” Gary uses this quote to link the visceral text and loaded reference of the motel sign, seamlessly merging Morrison’s poignant reflection with America’s history of white supremacist violence. “For some reason, when we talk about the horrific things that happened to us, we are now the perpetrators. That is how white supremacy reconstitutes itself,” Gary explains when reflecting on the work’s criticism. “[Whiteness] has created the false notion that it is neutral, it is default, it is the very definition of objective, it’s invisible. Oftentimes it is imperative to center whiteness in order to pick it apart, isolate [it] and name its function.… Just because you’re centering whiteness doesn’t mean you’re buttressing it or supporting it.” Like Morrison, Gary is unflinching in her centering on the lives of and relationships between Black people, especially Black women and femmes, and our negotiations with racism, capitalism, and patriarchal violence.

Because the films at the core of her practice aren’t yet widely available through streaming and her expansion into object-making is still fresh, sharing her artistic vision with her extended family has always been a desire for Gary. “Even if we have changed or transformed, which happens all the time, there are still these kinds of innate triggers, reflections, and observations that come to bear when we are in the presence of our family,” she says while speaking about the response she’s gotten from the exhibition. Gary’s mother told her that if her solo exhibition at the DMA didn’t work out, Gary could always just “give a presentation” to her loved ones at a family gathering. The informality and accessibility of this notion is warm with a characteristically Southern “make a way out of no way” mentality, a heritage that Gary takes great pride in.

This artistic homecoming has helped bridge a gap in understanding for not only her loved ones, but also other Dallas residents and visitors to the exhibition who are seeing themselves reflected in this carefully resurfaced archival material. No matter how personal, there’s a collective universal enjoyment of witnessing the aunties, cousins, sisters, and grandparents that make us feel like we’re in the company of our own. Gary’s work exemplifies the power and magic of returning to your point of origin.