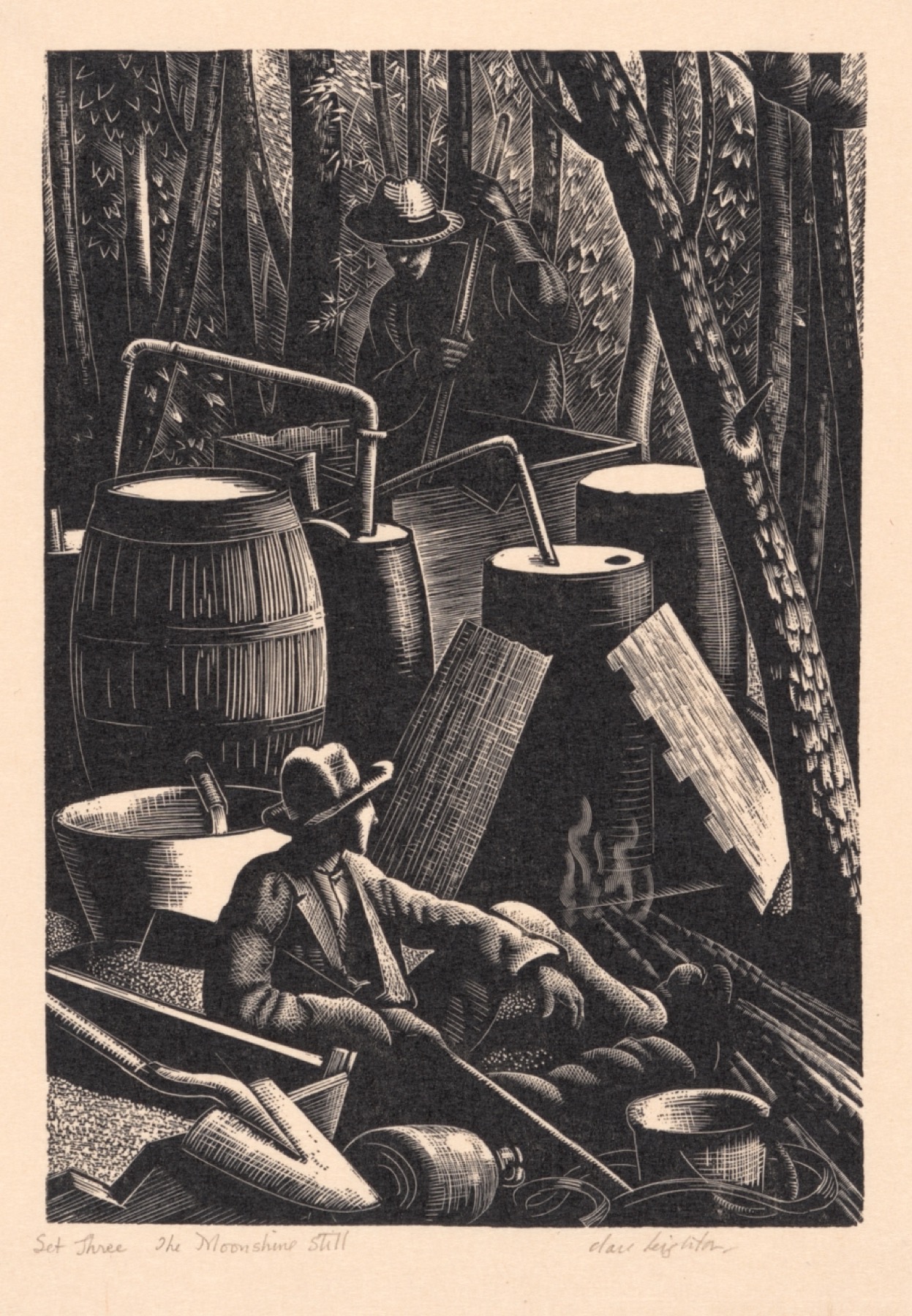

"The Moonshiner Still," by Clare Leighton. Ackland Art Museum, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, transferred from the library collection, 58.17.105. Courtesy of the artist's estate

The Art of Distillation

By Phil McCausland

Rusty Hanna’s boots crunched on the damp sticks and mushy leaves of the forest floor, his breath a cone of steam in the dawn. It was uncommonly cold out and sleet started to fall in the dense woods of the Mississippi Delta, a little snow collecting on logs and rocks. Hanna pulled his jacket tighter and looked over at his partner, Andy, a ways off to the side. The two were new hires at the Alcoholic Beverage Control (ABC) of Mississippi, the department that has regulated alcohol sales in the state since the legislature overturned its alcohol ban in 1966—the last state to repeal Prohibition. In 1985, one of the department’s main tasks was to investigate moonshiners, who continued to proliferate under the archaic liquor laws, and on this morning Hanna and his partner hoped to make their first bust. They’d been told that if you walked in the woods long enough, you’d find a working whiskey still.

The officers scrambled up the side of a slick hill and peered down into a small valley. Hanna cracked a smile. Next to a shallow creek, two elderly black men wearing stocking caps and loose work coats were cajoling a weak fire that sparked and crackled with the morning’s precipitation. The mash cooked slowly, nowhere near the 173 to 176 degrees Fahrenheit necessary to brew a crystal clear, high-proof whiskey. About an inch from the cooking kettle, they’d pushed scrap tin sheets into the frozen earth and stuffed old sugar sacks and cottonseed husks into the spare space for insulation. It was a crude operation, nothing like Uncle Jesse’s enterprise on The Dukes of Hazzard.

The officers made their way down to the pair of moonshiners and went through the typical rigmarole of an arrest, everything they’d been taught. But before they started busting up the still with the axes they’d brought along, Rusty Hanna said something that caused all parties to freeze: “Now we’re gonna cook some whiskey.”

The elder of the two men and owner of the still, a Mr. Banks, looked at him with squinted eyes. “No, we ain’t.”

“Yes, we are,” said Hanna. “The penalty is over.”

At the time, the consequence of operating a whiskey still in a wet county was only a misdemeanor, which constituted a small fine. (In a dry county it would’ve been a felony.) But with the arrest completed, Hanna wasn’t concerned about the possible repercussions of participating in illegal activity, while in uniform no less. He just wanted to learn. So for a few hours, the officers and moonshiners worked together to make a fresh batch of whiskey, Hanna gaining insights into the distillation process. For the next thirty-one years of his career, Hanna would come back to those lessons. He maintains that he learned more from Mr. Banks than he ever could have from a fellow agent. “I always felt obliged to that man,” he told me.

For their help after that first bust, Hanna gave each man a gallon of the whiskey and a ride back to their homes. He told them to go see the judge and pay the fine. “They asked me, ‘You gonna let us keep this gallon of whiskey?’” Now Mississippi ABC’s chief of enforcement, Hanna shrugged as he sat in a leather chair behind his desk, recounting this story. “I said, ‘Yeah.’”

I met my moonshiner in college. We shared a creative writing course at the University of Mississippi. Our professor demanded that each of us bring a fresh detail to every class: something noteworthy or subtle, interesting or useful we’d observed or learned since the last time we’d met. Students shared trivia (police use chalk outlines only when the victim survives) or described a poetic image they’d seen (a spider web bejeweled with morning dew; a tree’s shadow reminiscent of the female form).

One classmate, a ponytailed, bearded man in his early thirties who looked three parts rock & roller and one part survivalist, told long stories instead. Yarns about his kids, the war he’d fought in, the time his dog was kidnapped by a stranger and the car chase that ensued. (The stranger returned the pet after staring down a gun barrel.) We never interrupted him because we wanted to hear the conclusions, always punctuated with a gregarious belly laugh that seemed to suggest how goddamn lucky he felt. I’ll call the guy Danny.

Years later, on my way home to New Orleans after a nostalgic Fourth of July romp in Oxford, I drove into rural Mississippi for a meeting with Danny. A sub sandwich wrapped in white butcher paper sat atop the notebook on my backseat. He had agreed to talk about his experience brewing whiskey and introduce me to some of his ’shiner friends; the price of admission, he told me via text, was a Jimmy John’s “Gargantuan” with oil and vinegar. I fitfully eyed the sandwich as if it were a small child entrusted to my care. I didn’t know Danny that well—we hadn’t spoken since he took me out to his sedan after class one day, its trunk filled with mason jars—and I didn’t want to fuck this up. Members of the moonshining community don’t feel much kinship toward outsiders.

I passed the dirt road turnoff to his house three times before I finally spotted it. At the end of the drive sat a double-wide, its well-worn wooden steps leading to a ragged screen door. As I got out of the car and walked toward the stairs, a hound came bounding from around back, one of its eyes glassy, the size of a golf ball, and dimpled like one, too. It began to howl at me, and then the door opened and Danny yelled at the dog to pipe down. He was clean-cut—no beard or long hair. He wore a stained t-shirt and athletic shorts. He’d quit ’shining.

Between his job as a salesman and the MFA he was working on, Danny kept busy eighty hours a week. I’d interrupted his writing. The professor had said his work was too gritty and violent, Danny told me, swiveling back and forth on his computer chair. The professor wrote young-adult novels.

None of Danny’s friends were willing to talk to me, he said; they were too suspicious. But he could tell me plenty about moonshine—that was how Danny paid the bills when we were in school together. “I did it when I needed books for school,” he said. “Fuck, I need a thousand dollars real quick, these goddamn books are expensive—make a batch of moonshine. Real easy money, real quick. I had four guys who knew knew, and they were frat guys in Oxford. I would sell to them and they’d disperse it. It was like any other drug manufacturer. I had Ole Miss moonshine locked down. It took a day to get rid of ten gallons worth of moonshine.” His product went for eighty dollars a gallon, and this is why most moonshiners continue the trade.

It is possible to claim whiskey distilling as one of the earliest American professions; some even argue that the trade is a vertebra in the backbone of our modern political system. After secretary of the treasury Alexander Hamilton placed a controversial tax on whiskey in 1791 (the first on a domestic product), nontaxable liquor—or, as we know it today, moonshine—was born. In response, an anti-Federalist opposition party emerged, led by Thomas Jefferson, and the controversy blossomed into a conflict, culminating in the Whiskey Rebellion, a three-year squabble that only ended once President Washington roused 13,000 militiamen. It was the initial litmus test of the United States, which proved to the people (and to itself) that it could govern with sovereignty. But this authority did not quell the desire for untaxed alcohol, and maverick distillers disappeared into the foothills to continue their practice of farming and brewing the colorless, powerful liquor away from the reach of the government.

Danny learned how to make hooch when he got out of the Army. He’d been playing music with an older man for a couple years, when the man divulged that he was a longtime moonshiner. He didn’t have any sons, and his daughters never took an interest in the practice, so he asked Danny if he’d like to learn the classic American art of distillation. Danny claims it helped fix him after his stint in the military. The process provided structure, one step after another, and he found some semblance of peace in the long hours of waiting to turn the tap. He started making whiskey alone in the woods surrounding his land. The setting suited him—Danny’s preference is for privacy. That’s why he resides out in the deep country on a plot of land meant for hunting rather than living. That’s why he drives four hours to get to his desk job. He likes being alone with his family. As he spent more time outside, he grew accustomed to the woods.

Still, he never considered it more than a lucrative hobby. Once he started his new job, Danny loaned his whiskey still to a buddy and hasn’t seen it since. But he can get moonshine when he wants to. Every once in a while a friend decides to brew some on a stovetop, and there are a few ’shiners in the area who subsist on selling illegal booze.

“They each have their distinct taste, recipe, everything,” Danny explained to me, extinguishing a cigarette in an ashtray next to his computer. “One guy has got this new thing called Froot Loops. I swear to God—I don’t know how he makes it, but it tastes like goddamn Froot Loops. I don’t know what is in this shit, but it tastes like fucking Froot Loops, man! It’s the most delicious goddamn liquor you’ll ever taste in your life.”

I never got a chance to taste that liquor. It was late afternoon, and I still had a six-hour drive back to New Orleans. Danny said he’d make a few calls; maybe I could come back up for a visit with someone still active in the trade.

In Mississippi, there are longstanding traditions of moonshining and of publicly denouncing alcohol. The state passed Prohibition in 1908, eleven years before it was ratified into the Constitution, and kept it on the books until 1966, more than three decades after it was repealed in Washington. That’s almost sixty years of out-of-sight boozing, though one didn’t have to go too far out of the way to find it.

Biloxi was never parched, thanks to the rumrunners along the Gulf Coast; but access to liquor could be gained inland as well. In the 1930s, boozers and gamblers held court in view of Jackson, just across the Pearl River in Rankin County. A one-mile drive from the heart of the state’s capital over the Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge dropped you onto the strip, which comprised a few dozen shacks outfitted with bright neon signs belying the lavish bars and state-of-the-art gambling equipment inside. The area came to be known as Mississippi’s Gold Coast, where the preachers, constables, and lawmakers who sneered at its immorality by day gambled away their families’ savings by night. For a time, the gambling halls advertised in local newspapers with impunity.

The Gold Coast took off when an entrepreneur named Sam Seaney saw an opportunity to grasp the thirsty, immoral heart of Mississippi in his hands and pounced. His first bootleg enterprise opened around 1934. Seaney sold alcohol out of the back of the Jeep Tourist Court, importing legal booze from Louisiana and other surrounding states. Soon he was operating multiple establishments, including the Shady Rest and the Blue Flame (also called the Spot). Other enterprisers followed, among them the brothers G. W. “Big Red” and X. L. “Little Red” Hydrick, and J. H. “Doc” Steed, a convict with narcotics priors who came over from Hot Springs, Arkansas, to open the Blue Peacock. It didn’t take long for competition to bloom—in the form of the Oaks, the Green Frog, the Maple Grove, and the Wild Owl—and Rankin County earned a second nickname: Mud Hollow Monte Carlo.

Sheriffs came and went, some enforcing the laws, others willing to let them pass by in exchange for whiskey. Those who attempted to dismantle the operation found their lives disrupted: one lawman quit after a bottle split his skull; state newspapers embarrassed a governor into silence; a teetotaler sheriff saw his draft number called in 1942, an event he claimed had been orchestrated by bootlegging conspirators. A former Rankin County club owner named Joel Lundy described the period to the Jackson Daily News in 1983: “People drank more whiskey then than they do now. They just love to buy something that you say they can’t have. They’ll buy ten times more whiskey off the grass than off the shelf.”

Governor Hugh L. White raised a Whiskey Rebellion–style militia to bust up the growing strip in 1939. It yielded the largest seizure in the history of the Gold Coast, but it had no lasting effect on the illegal economy. The chief of the raid, Major T. B. Birdsong, noted that illegal activity “mushroomed back after the raiders sheathed their hatchets.” The closest the Gold Coast came to shutting down was after a Western-style shootout between the bootlegger Seaney and Constable Norris Overby, a lawman who saw the area’s existence as a personal affront. On August 28, 1946, the men scuffled in the midst of the crowd at the Shady Rest, then both pulled their weapons and shot each other at almost the exact same time. Seaney fell down a short flight of stairs and Overby flew back six feet. From the floor, the two continued to shoot their remaining rounds as they each expired. It was a national story and an embarrassment for the Mississippi elite, but the laws remained.

The fallout from the incident slowed but did not stall the action on Mississippi’s Gold Coast. It became a frequent stop for touring jazz and blues musicians during the 1940s and ’50s, and the residents of the state capital kept Rankin County bustling for a while more. Finally, in 1966, Mississippi repealed its outdated laws, and a referendum mandated that counties would decide whether to go wet or stay dry. In a speech to the state legislature, Governor Paul B. Johnson Jr. said, “It is high time for someone to stand boldly in the front door and talk plainly, sensibly, and honestly about whiskey, black-market taxes, payola, and all of the many-colored hues that make up Mississippi’s illegal aurora borealis of Prohibition.”

A few months after my first visit, Danny found somebody willing to talk, so I came up for a meeting on a Sunday. When I arrived, he seemed tired. His sons were running around the house and he had a buddy over. They were playing video games on different TVs. “Doc’ll be here in a little while, I think,” Danny said, as he picked up his PlayStation controller and returned to his game. I asked him how things were going with the MFA and at work, but he only offered one-word answers. “I just don’t want to have to think about anything,” he said. I was intruding on his day off.

I pulled back from asking questions and busied myself with watching his game. Ten minutes later, Doc arrived. An affable older man who told me he had grown up in the “Southern redneck hunting culture,” he asked me a few questions about myself and made it clear that he is not one to brew whiskey personally. “I don’t want to spend my golden years in Parchman,” he said. Then he fished through his bag and produced a flask. “This isn’t moonshine, either,” he added, holding up the metal container.

Doc sold himself as a connoisseur of moonshine liquor or most anything distilled in a private home. From blueberry wine to peach brandy, he dug it all, and claimed he could tell the type of yeast and mash used in a liquor, as well as its exact proof, from one deep swig. But something told me that Doc was implicated more deeply in the moonshine culture than he let on. When he discussed brewing, he said “we” did this or “I” did that, and I wondered if this was the man who taught Danny how to cook. But again, moonshiners don’t tend to give themselves up. I remembered what Rusty Hanna had told me at the ABC office: “The moonshiners from the old days just have a lot more loyalty. They came from a time when a man’s word meant something.” There’s a code.

Doc’s description of the moonshiner’s secrecy matched up: “You know, you move into a town and you’re there for about fourteen and a half minutes and somebody is trying to sell you some pot,” he said, toying with the top of his flask. “If you’ve been there for six years, somebody you’ve known for the last five and a half years will tell you they’ve been making liquor for the last twenty and you had no idea it was happening.”

Realizing he would never show his hand, I kept my suspicions to myself and instead asked how one can tell if they’re dealing with quality moonshine. Doc counted off four points across his fingers: clarity, proof, bouquet, and the burn.

First, the liquor should be crystal clear. As it sits in its jar, you should have to search for the seam between the liquid and the air. If it’s cloudy, that’s poor craftsmanship.

The next is proof, he said, picking up a Captain America action figure handed to him earlier by one of Danny’s kids. “I prefer it cracking up around the 120s or 130s. Occasionally if it’s higher, that’s okay, too. I’m not ever guilty of cutting anything down. But, during a normal run, you’ll have an initial segment of body and a tailing segment and the proof is highest after about seven minutes into the run and then it begins to taper off a half hour into it. We normally separate those out, so you’ll have a higher proof, and you can mix those back together.” A handy way to check is to dip your finger into the ’shine and then light it, he told me. If the flame burns blue, you’re up there. The beads are good indicators, as well. Shake the jar and the speed at which the bubbles burst indicates the potency: the quicker the pop, the higher the proof.

Then there’s bouquet. If it’s made with corn, there should be the sweet smell of fermented maize. Allegedly R. L. Burnside passed Doc the best corn whiskey he ever had many years ago at a wedding. The bluesman brought the ’shine with him in a Thermos, and when he took the lid off, the whole room stank of the stuff.

Finally, the burn. As it hits your mouth, there should be a nice under-burn between the teeth and lips. Not a scald, but a definite tingle. As it follows down the throat, it should be smooth to the gullet, but when it hits your stomach there will be a rebounding effect, an afterglow. “And all of a sudden you go—” Doc took a deep breath in and exhaled triumphantly. “Like a good cognac.”

Doc handed the action figure back to Danny’s son and took a swig from his flask. “This is the beginning of chemistry,” he said, smiling, with a look like Carl Sagan explaining that we’re made of starstuff to an audience of wide-eyed stoners. “Man’s learning to distill things—it’s all been downhill from there, as far as I’m concerned. But this is the beginning of modern science and chemistry and probably the best part of it.”

Moonshiners claim illegal distillation is a dying art form. Law enforcement goes back and forth on its prevalence. If you check Mississippi newspaper archives for the past eighty years, an article from one year will declare moonshiners long gone and another from the next will declare that it’s on the rebound. By its very nature, the trade remains secret, which is why it’s misunderstood.

Today, Mississippi claims two liquor distilleries, each opened in the past six years: Bottle Tree Beverage Company—mostly known for its Cathead Vodka brand—and Charboneau Rum Distillery. Mississippi’s ABC isn’t overtaxed by monitoring them, nor does the department trouble itself with busting up whiskey stills as often anymore, much to Rusty Hanna’s chagrin. “In the old days, the guys who worked before me—they had to have had a ball,” he said. “I knew a guy who came to work in 1966 as an original ABC agent, one of the first people hired. He was busting whiskey stills every day.”

There was a powerful level of nostalgia in each of my conversations with Hanna, Danny, and Doc. Hanna wants to carry out more busts, but he has to focus on underage drinking. Danny wants to brew moonshine, hang out at home, and write, but he works eighty hours a week. Doc just wants to go back to the time when passing a jar of moonshine with blues musicians was commonplace and not a special occasion.

Danny spoke of moonshining as an everyman’s craft and saw the state as being mired in just another confusing hypocrisy, as it was during the reign of Prohibition and the Gold Coast. “I don’t know, man. It’s Mississippi—you never know what the fuck is cool and not cool between anybody,” he told me during my first visit. “You have to keep everything to your chest until somebody shows you their cards and then you go along with that until they can fucking see you and you’re back to whoever you really are.”

These words are reminiscent of the story Hanna told me in his office at Mississippi ABC. Displayed on the wall was a framed black-and-white photo from the day of that first bust in 1985. It shows Hanna beside the smashed and smoking still. He keeps other pictures for his personal records. In one, he and his fellow agent pose with Mr. Banks and his partner, the green lawmen and seasoned ’shiners standing shoulder to shoulder. Though the photo doesn’t reveal that they’d just finished making a batch of whiskey together, if you know the story then you can see something telling in their faces—two agents with axes in hand and the moonshiners huddled in the cold, everyone stripped of their secrets.

“I had a soft spot for him,” Hanna recalled of his onetime mentor and occasional adversary. “He literally lived in a shack, on a one-hundred-dollar Social Security check. As he told me: ‘Rusty, I’m just trying to make a little money to survive. I’m making it to sell, not to drink.’” It was the truth. Hanna admitted that he arrested the man a handful more times, and then Mr. Banks’s son after he started distilling. Though Mr. Banks likely made only twelve to fifteen dollars per gallon, it helped him get by. Opportunity was scarce in the Mississippi Delta. It still is.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.